In the first of a two-part interview with TreatmentMagazine.com, the director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy discusses the opioid epidemic, harm reduction and a range of other topics

By Jason Langendorf

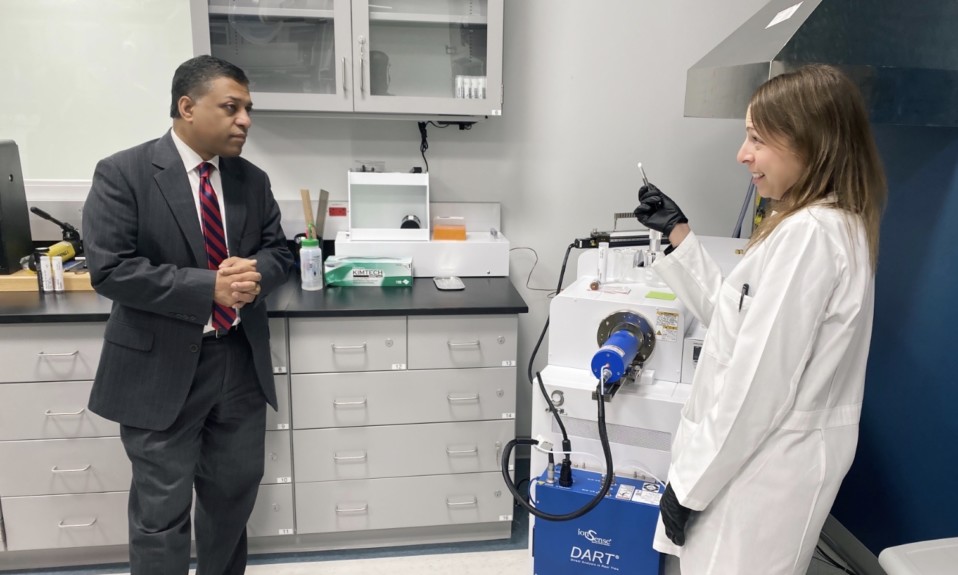

Having most recently served as the chief medical and health officer and senior vice president at March of Dimes, Rahul Gupta, MD, in October 2021 became the first medical physician to assume the role of director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP).

A former clinical professor in the Department of Medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine and adjunct professor in the Department of Health Policy, Management and Leadership in the School of Public Health at West Virginia University, Gupta is also a practicing primary care physician of more than 25 years. Born in India, Gupta grew up in suburban Washington, D.C., earned his master’s in public health at the University of Alabama-Birmingham and led state opioid response efforts while serving as health commissioner of West Virginia—key fault lines in the nation’s coast-to-coast addiction and overdose crisis.

During Gupta’s directorship, the federal government unveiled the nearly $4 billion American Rescue Plan, expanding access to vital mental health and substance use disorder services; released the Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder, expanding access to evidence-based treatment by removing a critical barrier to buprenorphine prescribing; and announced that federal funding may now be used to purchase fentanyl test strips.

TreatmentMagazine.com spoke to Gupta about policy, people and how to provide effective addiction care. Below is Part I of our two-part interview.

Q. How important is your distinction as the first medical physician to serve as director of the ONDCP, not just symbolically but practically speaking?

A. We have a public health crisis on our hands, with an American dying every five minutes around the clock, to the tune of 108,000 Americans dying in any given 12 months at this point. And those numbers are not only increasing, they’re increasing exponentially—meaning that even when you look at 2015 to 2021, that number doubled in those six years.

“[W]e know that roughly half of people who suffer from substance use disorder have co-occurring mental health disorders, and vice versa. So it’s really important for us to first recognize that fact and then, secondly, make sure that we have systems and programs in place.”

—Rahul Gupta

We also know, at the same time, the mentality around the drug supply and the lack of treatment infrastructure, the importance of connecting people to care. It requires an approach at the intersection of public health and public safety. But it also requires a deep understanding of the variety of factors that go into this particular epidemic—existing overdose deaths, the overlap with mental health, the understanding of where we are with provision of those systems of prevention, treatment, harm reduction and recovery, as well as working with our public health-public safety partnerships.

Q. You mentioned mental health. Too many treatment centers still aren’t making that connection with addiction, whether they’re missing or ignoring it, or perhaps making the effort but struggling to target the underlying circumstances. What is the nature of that disconnect?

A. As a practicing physician, I come at this from the perspective of looking at the individual. We’ve got to have policies, systems, programs—all of those have to be designed around the people we’re trying to serve. And that’s exactly what I’ve done and continue to do in my spare time seeing patients—trying to understand the needs of the individual.

From that perspective, we know that roughly half of people who suffer from substance use disorder have co-occurring mental health disorders, and vice versa. So it’s really important for us to first recognize that fact and then, secondly, make sure that we have systems and programs in place that help to facilitate access to treatment that addresses both, because it doesn’t help if we are addressing in our own silos.

It’s not something we haven’t done before. For example, we know the overlap between obesity, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease. I’ve seen thousands of patients and managed them. Similarly, there’s an overlap in [addiction and mental health]. Diseases in individuals tend to overlap, one with the other. And that’s where it comes in for me, as a practicing physician, to recognize that there’s a really important component and that we can’t ignore one for the other.

Q. That’s a great analogy, but the average person doesn’t always recognize it in those terms, instead seeing the former as physical ailments and the latter as a moral failing, like it’s the patient’s fault. How much does stigma still play a role?

A. So I go back to the office, and I see this office has historically focused a lot more on the supply side of the equation. And now we’re trying to make sure that we bring into policymaking what we know in science—which is, of course, that addiction is a brain disease. It’s one that not only hijacks the brain, but also has a consequential impact on you, your family, your community, as well as your productivity and future.

We get it that it’s going to take time to remove the age-old stigma that it’s a disease of choice. It is not [a disease of choice]. Stigma occurs not only within communities and systems, but even in the healthcare professions. Frankly, in my own profession, there are tremendous amounts of stigma around this. So it becomes really important for us to approach this in a way that we have approached and conquered many other chronic illnesses.

There are so many people with other physical conditions that may or may not have a mental health component. Sometimes they do. But this is another one of those examples where it has so many impacts in your life, and we have to approach it as a chronic disease. People are still human beings. And as human beings, they will also have, potentially, diabetes. They will also have high blood pressure. We’ve seen this with HIV. I used to run the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program in northern Alabama counties, and they saw that when we started to save people.

“[W]e have a nation that does not have an adequate addiction and mental health treatment infrastructure. Today, less than one out of 10 people in this country who need treatment can get it.”

To give you perspective, when I entered my residency in Chicago in 1996, the 12th floor of St. Joseph Hospital was filled with people coming in with HIV or AIDS. And dying. I was literally taking care of an entire floor, sometimes overflow, with people dying of AIDS. When I left—I finished my residency in 1999—the disease in those three years transformed from those individuals being inpatient with no treatment, literally you’re dying, to one of outpatient, where survival occurred [frequently]. We then changed it to a cancer floor.

And I bring that up because I have seen, in practice, diseases change form. But then I moved to Alabama, and one of the things I saw was that when people live longer with HIV, they also have the same kinds of conditions as anyone else—high cholesterol, diabetes, heart disease. So now we have to also make sure that people are getting screened for and treated for those illnesses, too. So having had that lived experience over time, it’s the same thing [with addiction]. The first approach has to be about saving people’s lives, connecting them with care and then, obviously, to create a person-centric approach to care—to see what the needs of the people are and be able to provide for those needs.

Q. To many in the treatment space, saving lives translates to harm reduction. But politically, those programs can be a tough sell. What is your response to the average person who sees states receiving legal payouts and the federal government increasing spending and commitments even as the overdose numbers skyrocket and says, “It isn’t working”?

A. The first thing I would say, and I often say, is understand that this is not your uncle’s drug epidemic. Today, what is new is that we’re dealing with the most dynamic drug-supply environment in our nation’s history. When we consider the prevalence of synthetic, potentially lethal opioids like fentanyl, the drug supply is as potent as it’s ever been in the history of this nation.

On the other hand, it’s being driven by pure profit, so we have to understand that from a transnational criminal organization standpoint. More importantly, we have a nation that does not have an adequate addiction and mental health treatment infrastructure. Today, less than one out of 10 people in this country who need treatment can get it. And I’m in the United States of America! So that’s where our approach toward policy and the President’s strategy is at, addressing these two drivers first: Make sure we build that treatment infrastructure, get people the help they need; then, secondly, go after the drug trafficking profits in a way that we recognize commerce. We understand that we have to now work to disrupt that commerce, the entire supply chain of production, manufacturing, pricing—all those pieces.

At the same time, the core of this is to humanize the issue. Our North Star should remain saving lives. That’s been the oath I’ve taken as a physician. That’s something that’s near and dear to me, which is to move with a very specific agenda and the goal of saving lives first. It’s a basic principle of triage, if you think about it—and that’s exactly what President Biden has been focused on, making it his top urgent priority.

Q. More harm reduction. That seems to be something the administration has either wavered on a little bit or muddled the issue. What is the White House’s current stance on harm reduction?

A. There’s absolutely a firm stance in the sense that, for the first time in the history of the federal government, we have in the present strategy very clearly delineated the approach of harm reduction. Which is obviously an approach that embodies meeting people where they are and treating people with respect, building engagement and trust rather than fear or judgment. And it’s an approach obviously vetted and embedded in science and data. But it’s one that’s needed now more than ever before because of the threats we’re facing from this dangerous drug supply.

Specifically, the present policies therefore call for three specific strategies that we term high-impact harm reduction strategies. That includes, first, naloxone. Naloxone is important because we know, when I mentioned those 108,000 people dying, that 80,000-plus of those people died because of an opioid. That, to me, as a physician, is unacceptable. That means we could have saved a majority, if not all, of those people. The fact that we have the opportunity to save tens of thousands of people, but they’re dying—it’s just unacceptable. One of the first things we can do is to make sure that naloxone is available to anyone and everyone, without fear or judgment, and to put it in the hands of people who can administer it with a lot of other strategies behind it.

“Every dollar invested in naloxone has returned about $2,800. It’s been recognized time and again as one of the best ways to save lives and actually save community dollars.”

Second is drug checking. It’s important because, as I mentioned, oftentimes when you’re using substances, you don’t know if your drug supply has fentanyl. So you might be using that same meth or cocaine or other substance for many, many years, and now it’s just been tainted with fentanyl. I think it’s important that you have the ability to check your own drug supply for fentanyl and make the appropriate decision. It is those deaths that are also preventable. Fentanyl test strips and drug checking have become core to this approach.

And the third part is syringe service programs. We know very clearly that harm reduction approaches like syringe service programs not only meet people where they are and prevent the spread of communicable diseases—which are often deadly and very expensive, like HIV and hepatitis. But they also build trust and connect people to treatment. They save lives. They positively impact crime [rates]. There’s so much evidence on that. Naloxone, for example: Every dollar invested in naloxone has returned about $2,800. It’s been recognized time and again as one of the best ways to save lives and actually save community dollars. These are the kinds of cost-effective strategies we’ve been very clear about from day one – that we need to make sure that people across the country, no matter where you live, have access to these standards.