Dad uses a treatment approach for his son that allows for accountability and healing

By a Dad

In retrospect, it’s kind of funny. Laughing is always better than crying, right?

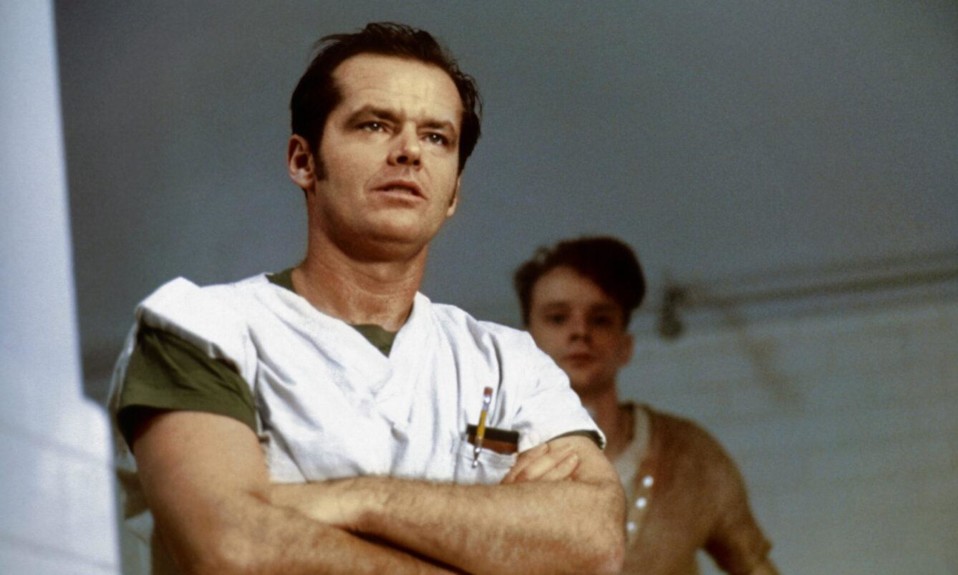

Think One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Imagine an uprising of sorts on a floor in a residential institution.

Only in this case, imagine the uprising is fueled by hallucinogens. Now imagine the hallucinogenic insurgency is instigated by my teenage son, the Randle McMurphy of this production.

I was blissfully ignorant of the episode as it was unfolding. Then late the next afternoon, I received a phone call from the CEO of the addiction treatment facility that had been home to my son for the previous few weeks. When the CEO introduced himself, my heart shot into my throat. Oh my God, he’s dead, I thought.

Think One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Imagine an uprising of sorts on a floor in a residential institution. Now imagine the hallucinogenic insurgency is instigated by my teenage son, the Randle McMurphy of this production.”

The CEO politely asked if we’d pick up my son ASAP. Within two hours, as a private security officer hovered over me, my wife and my son in the CEO’s office, we were going through the release papers. I remember only one line from that stack. It read, “Prognosis”; a box next to it that corresponded with “Poor” was checked. And then we were escorted out of the building. Just like that, my son was someone else’s problem.

As the three of us drove home in silence, my hands clenched white on the steering wheel, I racked my brain for a silver lining. The best I could come up with was that he had at least displayed leadership skills. Somehow it didn’t provide solace. What to do? By now, we were deep into “the system.” We were old pros, having steamrolled through a few treatment programs over the past couple years. Reflexively, we put him in another, this time an outpatient program that touted an emphasis on discipline. I thought this one might finally do the trick, but what’s the old saying? “The definition of insanity is repeating the same actions over and over again and expecting different results.”

I decided to yank him from ‘the system’ and admit him into the Treatment Center of Me. …It was an unorthodox move, to be sure.”

Sure enough, he was kicked out of the new program in short order. And as the cherry on this shit sundae, he then briefly ran away from home. The more we had kept pushing him to do things our way, the more he had dug in and done them his way. At a certain level, I respected his doggedness. But no question, I was going insane.

What to do? I decided to yank him from “the system” and admit him into the Treatment Center of Me, with a bit of support from his team. It was an unorthodox move, to be sure. But every kid is unique, and this seemed like the best—maybe the only—option for my son. We slogged along for a few months until he turned 18, at which point I felt like I finally had some leverage in this battle of wits. I said to him, “I’m no longer legally obligated to take care of you. If you want to keep living here, sign this contract.” The contract was short and sweet, with the bar set deliberately low.

As I recall, it went something like this:

- He was free to do drugs, but if he did them in our house, he was gone.

- If I found out he was dealing drugs, he was gone.

- If he earned lower than Cs at the community college he was about to enroll in, we’d stop paying his tuition.

- He had to get and keep a job, or he was gone.

Today he borders on being a teetotaler. And—get this—he has a free ride in a Ph.D. program at an elite school.

But I’m not here to go all Hallmark movie on you. That would be disingenuous. The credits didn’t start rolling when he opened his acceptance letter from that elite school. The truth is, the credits never start rolling.

I’ll always worry about my son. I’ll worry about him in a way I’ll never worry about my other kids. I don’t fear he’ll do a deep-dive back into drugs—they were never the root of the problem. I fear his anxiety and depression will resurface again and manifest in some other manner.

I’m not here to go all Hallmark movie on you. That would be disingenuous. The credits didn’t start rolling when he opened his acceptance letter from that elite school.”

So, where’s the hope in all this? Today, anyway, it’s right in front of me. Tomorrow might wind up being an unmitigated disaster—you never know, regardless of the safeguards you put in place—but this moment in time is pretty damn good. And come what may, I know from experience that the cause is never lost.