Plus: Guidelines for treating cancer patients who also have opioid use disorder, and the regulatory pipeline brings forth too many high-risk painkilling meds

By William Wagner

Hangovers are among the many ills connected with alcohol use. A new pill, though merely a Band-Aid for the harm alcohol can do to a person, aims to make the morning after less rocky.

We also focus on two opioid-related items: new guidelines for treating cancer patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) and the flood of high-risk pain medications.

From The Conversation:

Myrkl’s Anti-Hangover Supplement

The Swedish pharmaceutical company Myrkl has introduced a pill designed to dramatically lessen hangovers. Now on sale in the U.K., the pill is taken before drinking and supposedly absorbs 70% of alcohol consumed. It works by stunting the amount of alcohol that enters the bloodstream. That also means a person who takes the product will become less “drunk.”

But does it really work? According to The Conversation, Mrkyl’s claims are based on just a single study, in which 24 young white adults took either two of the company’s pills or placebos for a week each day before drinking. The participants’ blood was tested continuously for two hours after they began drinking. Following the first 60 minutes, those who took the Myrkl pills had 70% less alcohol in their bloodstream than did people from the placebo group.

“[T]he best cure for a hangover remains drinking less alcohol the day before.”

—from The Conversation

The Conversation, however, identified “problems” with the study: “First, the researchers only reported results from 14 of the 24 people because ten had lower blood alcohol levels at the start. Second, results varied between different people, which reduces the accuracy of the study. And third, the researchers tested seven days of treatment before a single drink of alcohol, but the company recommend only two pills one to 12 hours before drinking any amount.” Finally, as The Conversation notes, “the best cure for a hangover remains drinking less alcohol the day before.”

From JAMA Oncology:

How to Treat Cancer Patients Who Also Have OUD

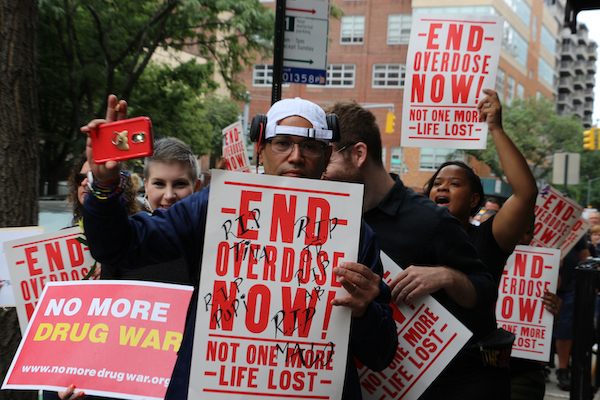

Given the physical pain associated with cancer, patients suffering from the disease who also have OUD are particularly tricky to treat. In order to help mitigate the addiction risks while also providing necessary relief, a research team led by the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine has developed guidelines for treating cancer patients with OUD.

“There is no standard of care for treating cancer pain and managing opioids in people who come into their cancer diagnosis with a history of substance use, or who are at increased risk for adverse events due to prescription opioid misuse behaviors, such as taking more opioids than prescribed,” says Katie Fitzgerald Jones, MSN, first author of the paper. “As a first step towards improving care of these patients, our study surveyed clinicians to understand how they treat patients with opioid complexity.”

The recommendations center on methadone and buprenorphine, medications that have been successful in combating OUD. In the case of cancer patients, say the paper’s authors, prescribing regulations must be loosened to provide better access to these meds. The barriers are part of a larger problem, one that leads to subpar care. “Because of the way that methadone and buprenorphine are regulated—one way for pain, another way for addiction—addiction treatment is isolated from mainstream medical care, including cancer care,” says senior author Jessica Merlin, MD, PhD. “It’s othering, and it adds to the stigma of opioid use disorder.”

From Anesthesiology:

The Onslaught of High-Risk Pain Meds

As the opioid epidemic rages on, researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and MIT School of Management have made a distressing discovery. High-risk pain medications, or those with greater addiction potential, are more likely to be granted regulatory approval than low-risk meds. Analyzing 496 pharmaceutical development programs between 2000 and 2020, the researchers found that 27.8% of pain medications deemed to have high abuse potential were greenlighted, compared with 4.7% with low abuse potential. Although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put tighter developmental regulations into place in 2010, more drugs with high abuse potential than low still received approval in the ensuing 10 years, though the percentage did drop.

“Despite the widespread prevalence and high societal costs of both pain and addiction, investment in therapeutics in both areas remains underfinanced.”

—study in Anesthesiology

The problem, the authors write, is more complicated than meets the eye: “Despite the widespread prevalence and high societal costs of both pain and addiction, investment in therapeutics in both areas remains underfinanced. This has taken place for a variety of reasons, not least of which is the poor understanding of the probability of successful development of pain medications. A poor understanding of the probability of successful development prevents accurate modeling of the risks involved in pain pharmaceutical development.”

Top photo: Shutterstock