A new study reveals that limited availability of the medication doesn’t bode well for those suffering from opioid use disorder

By Jason Langendorf

The supply of methadone in the United States declined “significantly” during the pandemic and has yet to return to previous levels, while the supply of buprenorphine increased only slightly over the same period of time, according to a new report.

A cross-sectional study published last week on the JAMA Network used quarterly data detailing the U.S. per-capita supplies of methadone and buprenorphine, medication-assisted treatments (MATs) that are used in the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD). The study authors observed a 20% decrease in the methadone supply in the second quarter of 2020 (compared to an 8% decrease the previous quarter), while the buprenorphine supply saw “stable growth.”

“Future research examining state disparities is needed to help improve timely access to methadone for patients with OUD.”

—JAMA study

The study’s corresponding author, Bradley Stein, MD, PhD, a senior policy researcher and director of the Opioid Policies, Tools and Information Center at the RAND Corporation, found the resulting decrease in available MAT—at a time when the overdose crisis began raging across the country like wildfire—troubling.

As Stein told U.S. News & World Report, “The fact that methadone decreased, has sort of stayed down, and doesn’t really seem to have been compensated by buprenorphine is something that sends up a red flag as far as if there is a problem in some places in ensuring that patients still have access to these effective interventions.”

The Importance of MAT

Almost 20 years have passed since the World Health Organization (WHO) added both methadone and buprenorphine to its list of essential medicines. Physicians in addiction facilities, emergency rooms and as high up as the Office of the Surgeon General have in recent years taken to categorizing them (as well as the MAT naltrexone) as part of the gold standard for treatment of OUD. These medications unequivocally save lives:

“All three of these treatments have been demonstrated to be safe and effective in combination with counseling and psychosocial support,” the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states on its website. “Everyone who seeks treatment for an OUD should be offered access to all three options as this allows providers to work with patients to select the treatment best suited to an individual’s needs. Due to the chronic nature of OUD, the need for continuing MAT should be re‐evaluated periodically. There is no maximum recommended duration of maintenance treatment, and for some patients, treatment may continue indefinitely.”

But because regulations stipulate that methadone must be administered daily, at a designated clinic (whereas buprenorphine can be taken orally at home, or via injection from any doctor), people who use methadone are often more visible—and thus more stigmatized. Even as Pew Charitable Trusts heralded the addition of methadone clinics in some states during the pandemic, it noted that “crowded parking lots, long lines and the potential for diversion of the medication have led many states to limit the number of clinics they license.”

Even as federal regulations were loosened during the pandemic to allow some patients to receive multiple doses of methadone to be self-administered, the changes amounted to half-measures.

In fact, the authors of the JAMA study found “pronounced geographic disparities in methadone distribution between states … from nearly 50 percent decreases in New Hampshire and Florida to a 26 percent increase in Ohio.” In other words, in some states where stigma was already rampant, access was limited and regulations forced many people attempting to overcome their addictions to make daily visits to a clinic, public policy may have been behind the suppression of the methadone supply.

Even as federal regulations were loosened during the pandemic to allow some patients to receive multiple doses of methadone to be self-administered, the changes amounted to half-measures. And in clinics in some states and regions, they had a net-zero effect.

“Just because policies were relaxed,” Stein said, “doesn’t mean that all clinics changed what was going on in the clinic to take advantage of those relaxed policies.”

What to Do About the Methadone Shortage?

With opioid overdose deaths still reaching all-time highs month over month, the need for FDA-approved medication-assisted treatment has never been higher. Yet the availability of and access to MAT, particularly methadone, appears to be diminishing.

If current trends hold, patients with OUD won’t have time to wait for additional research to sway progress-blocking states and policymakers.

As Stein and his co-authors write in JAMA, “Future research examining state disparities is needed to help improve timely access to methadone for patients with OUD.” But the research is in: We already know MAT works. And we know disparities across states exist—and, in many cases, why they exist. If current trends hold, patients with OUD won’t have time to wait for additional research to sway progress-blocking states and policymakers. Many of them won’t be around to see the benefits.

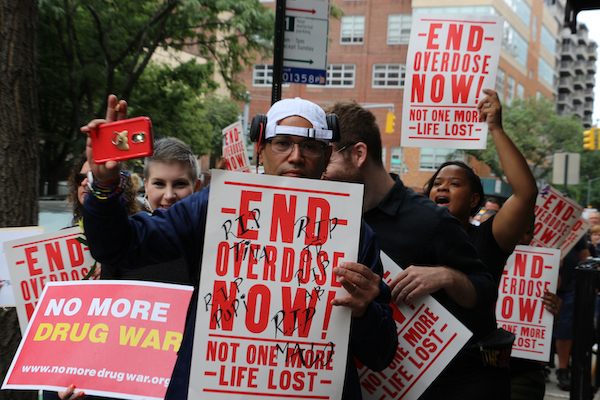

Photo: Shutterstock