U.S. Senate committee raises conflict-of-interest questions, but delivers no concrete path forward

By William Wagner

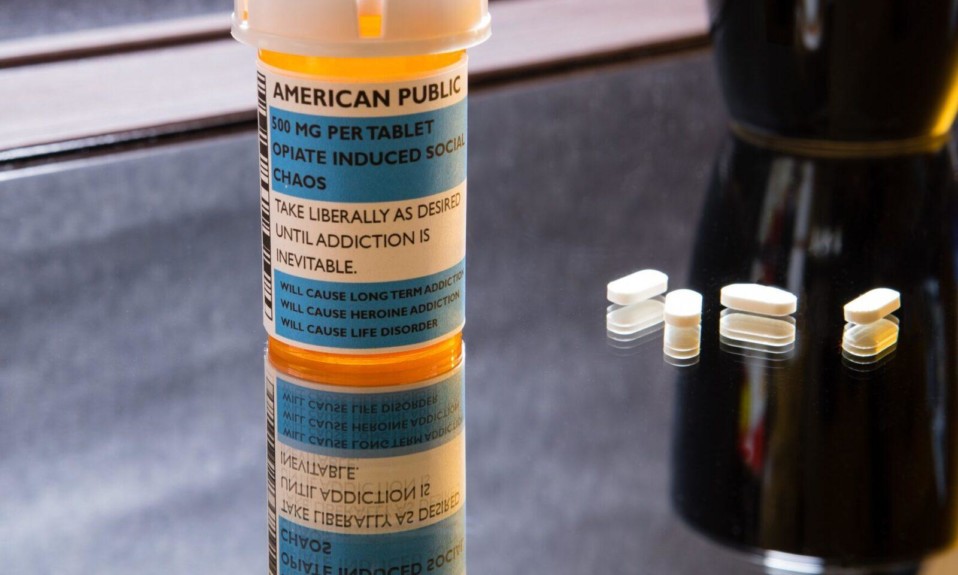

January 5, 2021Lost amid the political intrigue following November’s presidential election and the ongoing horrors of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a key finding by the U.S. Senate Finance Committee linking opioid manufacturers to advocacy groups. Headed by Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), the bipartisan committee wrapped up an investigation in December that determined opioid manufacturers have funneled $65 million since 1997 to nonprofit groups that advocate for treating pain with medications.

The goal was to boost sales of prescription painkillers, and the money kept flowing even as the U.S. opioid epidemic turned increasingly dire. Since 2000, opioids have been connected to nearly 500,000 deaths in the United States.

Are you blindsided by the committee’s revelations? Courtney Hunter, vice president, state policy for the addiction nonprofit Shatterproof, says you probably shouldn’t be.

We’ve found that the possibility of donor influence could and has undermined the efforts to develop and advocate good policy.”—Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa)

“Sadly, I’m not surprised,” she says. “I continue to be outraged by the information that comes to light with regard to opioid manufacturers and distributors, and how they funnel money into patient advocacy groups to further their [sales] efforts despite the ongoing lack of access to treatment for addiction.”

The committee seems to have a general sense of where to go from here, but there are no specific legislative remedies as of yet. “We’ve found that the possibility of donor influence could and has undermined the efforts to develop and advocate good policy,” Grassley said in a statement. “When it comes to opioids, we need to make sure there is transparency and accountability to prevent what, in this case, led to serious public misunderstanding of the risks of these highly addictive drugs.”

10 Opioid Advocacy Organizations Studied

As part of its work, the committee dug into the ledgers of 10 advocacy organizations that had championed the use of prescription painkillers from 2012 to 2019. The drug companies that gave the most money to advocacy groups during that period were Teva, Pfizer, Insys and Purdue Pharma; each contributed at least $2 million.

The way the committee sees it, the motivations and repercussions are clear. “The potential dangers presented by opioids make this Trojan horse-style marketing particularly troubling,” Wyden said in a statement about the findings of the investigation, which was a continuation of Senate probes that had looked as far back as 1997. “But make no mistake that such practices are widespread across the pharmaceutical industry, and consumers are often left in the dark,” Wyden added.

And that, says Hunter, is the shame of it all: “They could have used those $65 million to really help people. That’s what stings the most. Now [some are] being sued for that and have to do it retroactively, but how many people have died in the meantime?”

Hunter believes the whole system needs a second look.

“These nonprofit advocacy groups really blur the lines of what is appropriate for a tax-exempt organization,” she says. “Certainly, getting money from a corporation as a tax-exempt organization is fine, but are these physician groups? Patient advocacy groups? Arms of the pharmaceutical companies? It’s not really clear.

“There’s a huge lack of transparency about who these groups are. They don’t sound nefarious at all [on the surface], but they have people on the Hill. They’re meeting and also funding elected officials. That doesn’t seem like a good use of taxpayer dollars.”

Photo: iStock