Will died of a heroin overdose in 2012—but his body continues to contribute to the common good

By Bill Williams

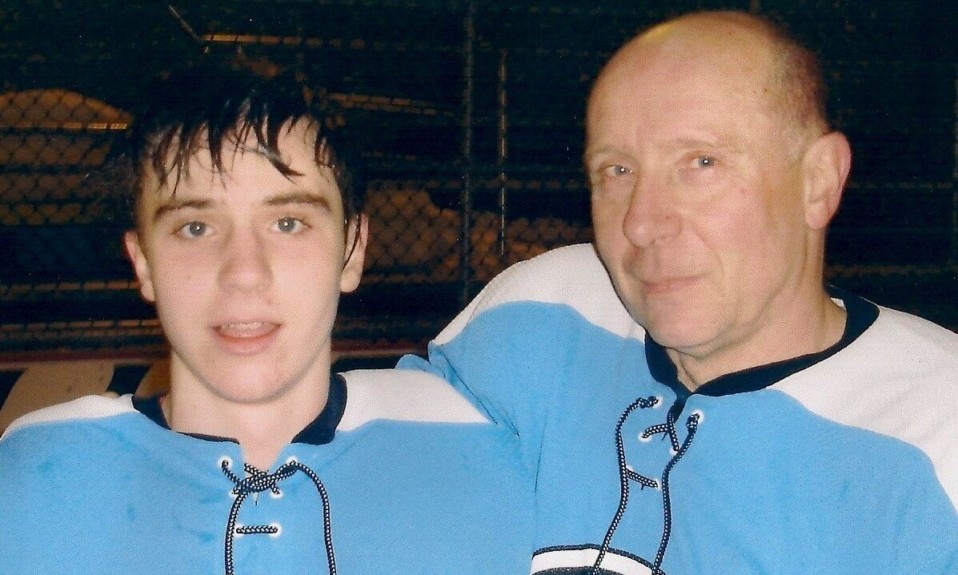

January 5, 2021Spoiler alert! My son, William, died from a heroin overdose in December of 2012.

You might ask, “Where’s the hope in that?”

For nearly two years before, our family lived with all the lies, fights, blame, doubt, struggle, sleepless nights, apprehension and more that come with a family member’s substance use disorder.

Apprehension became fact when William accidentally overdosed in our living room. I discovered him there and frantically called 911. As a result of his acute intoxication, when his heart stopped beating for too long, despite extraordinary work by emergency personnel, William was placed on a protocol called therapeutic hypothermia to cool his body in an attempt to prevent brain damage.

The night William first arrived at the hospital, I asked two resident doctors if a heroin user could be an organ donor. To my surprise and relief, the answer was yes.”

Six weeks of comatose and/or heavily medicated hospitalization followed—six weeks of a family bedside vigil—before a neurologist used the analogy of “cut flowers in a vase” to explain the state of William’s brain. The cut alone is damaging. Yet, initially, the freshly cut flowers look fine. As time passes, they shrivel, wither, and dry up. We had to comprehend and accept that William was consigned to a persistent vegetative state.

There would be no miracle. William would blossom no more.

The night William first arrived at the hospital, I asked two resident doctors if a heroin user could be an organ donor. To my surprise and relief, the answer was yes.

We made the agonizing decision to remove William from life support and contacted the New York Organ Donor Network. Our admiration for its dedication, compassion and professionalism knows no bounds. Organ donation for someone in a vegetative state requires an expedient demise once removed from life support. William did not expire within the necessary one-hour time frame, though his mother, sister and I were with him in the operating room, singing to him, talking to him and telling him what he could not comprehend, that he could let go.

He lasted another 21 hours before drawing his last breath in our arms. William had been attached to monitors and machines for six weeks. The last thing I was able to do for my boy was to detach every wire and sensor from his body—to free him to be on his own. Determined that his death not be in vain, his mother, sister and I made the gift of his body, an anatomical donation, to the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. In another time, in a better era, William might have entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons not as a cadaver but as the gifted and talented young man he was.

The Story of Will’s Contribution

For some while, we knew nothing about the disposition of William’s body, other than that it had arrived at Columbia’s Medical School. In April 2014, we were invited to a moving memorial service conducted by first-year med students for donor families—but learned only that William was used for a special project, not the first-year anatomy lab.

In late winter 2018, we were contacted by a writer working on a piece for Columbia Medicine Magazine. She wanted to incorporate our family’s story into an article she was working on about opioids. I wrote her to respond that we had no idea how William’s body had been used. We knew it had been used somehow, as his ashes were presented to us at the 2014 memorial service.

She wrote back. “Will’s body was used to augment/improve the images and instructions in the iPad ‘manual’ used by Physicians & Surgeons students throughout their anatomy training. My sense is that the manual is constantly being augmented and improved (what with its being digital and so inexpensively revised). The instructor specifically mentioned how valuable it was to include images of Will’s anatomy, because being young and healthy, the images give a clear contrast with the various disease states students will encounter with their patients.”

An Anatomical Donation

About the time William died, Columbia medical students—dissatisfied with the classic manual Grant’s Dissector, first published more than 60 years ago, heavily reliant on drawings and still in wide use—initiated a project to compile thousands of photographs into a digital anatomy manual. Now the Columbia University Clinical Gross Anatomy Dissection Manual is available to anyone on iBooks. The fully interactive multi-touch book offers simple step-by-step instructions accompanied by photos of real dissections, a complete glossary for every bold term, and quizzes throughout.

I contacted Dr. Paulette Bernd, director of the gross anatomy program and editor of the dissection manual. She wrote back, “Most of us have these prejudices, whether conscious or not, with respect to addicts, those with mental illnesses, those who are obese, those who are uneducated, those with sexually transmitted diseases, etc. etc. etc. Overcoming these prejudices cannot begin until students are made aware that they exist and that people that have any of the above maladies should not be shamed or deemed inferior.”

She added that students using the digital manual right at the anatomy table are less frustrated, rely less on faculty and do better dissections—and they get better grades on both practical and written exams.

Our determination that William’s death is not in vain has been realized. Our Will will contribute to the common good for what we hope is a long time.

For more from Bill Williams and his ongoing work on behalf of his son, see his blog and follow him on Twitter at @BillEduTheater.