Founder and former meth abuser Cheri Garcia helps her clients in recovery and herself—by providing work opportunities, purpose and focus on mental health

By William Wagner

September 22, 2020Cornbread Hustle‘s Cheri Garcia is a 33-year-old dynamo, an entrepreneur who spends her days making her corner of the world a little better. As founder and owner of her Dallas-based staffing agency, she’s in the business of giving second chances to those trying to bounce back from addiction and/or incarceration.

But a word of warning before we delve any deeper here: Garcia doesn’t recommend following her career roadmap. In hindsight, she believes she started Cornbread Hustle in 2016 for the wrong reason, namely as a way to divert her focus from her need to quit drinking.

“Running my company has actually not been helpful to my own recovery because of my own self-destructive behavior and reasons for starting this company,” Garcia says. “I started this company drunk.” She adds, joking: “Thank God I was drunk, because I don’t know if I would have started a company banking on the success of people coming right out of prison if I was sober.”

To me, success and alcohol went hand in hand. I had a Wolf of Wall Street mentality where you’re not going to be successful if you can’t party hard.”—Cheri Garcia, founder of Cornbread Hustle

“So, I started the company impaired,” she says, “and I poured myself into everybody so that I could fill myself back up with alcohol at the end of the day. I wanted to fix other people so that I could avoid fixing myself and not acknowledge that I might have a problem. My advice to anyone who wants to quickly start a company that’s trying to help other people is to check your motives first and help yourself before you try to help others.”

A Dream Founded “Drunk”

Long before Cornbread Hustle came to be, Garcia was hurtling into the future like a blur. All the better to avoid a hard look in the mirror. In 2007, she broke an addiction to methamphetamine—cold turkey, without taking the time to ask for professional help or reach out to any outside support systems. In 2010 and ’11, she was an assignment editor for the CBS affiliate KTVT-TV in Dallas. Two years later, she received a patent for an inflatable tanning bed, Luminous Envy, she invented. You get the idea.

“I did get off meth in 2007, and I thought just because I was able to do that without going to rehab or working the 12 steps, I was the best thing since sliced bread,” she recalls. “I put success and money on such a high pedestal, and I was very confident. I thought I knew how to do life because I was a good entrepreneur. But oh my God, I drank every single day. Work hard, play hard. The entrepreneur scene is very social, with happy hours. To me, drinking alcohol every day and doing cocaine here and there to keep the party going or get up the next morning was just part of being an entrepreneur.”

With Cornbread Hustle, she had no particular plan—the enterprise developed organically. Looking to “pour herself into everybody,” she joined the Texas-based Prison Entrepreneurship Program in 2013, through which she traveled to lockups to help inmates develop business plans that would enable them to someday make a living and find meaning on the right side of the law.

“I started getting Facebook friend requests from people with neck tattoos,” she says. “I would meet up with these guys. They’d have 50 bucks, a bus ticket and no driver’s license. They’d have literally nothing to their name, living in a transition house. We’d be looking at their business plan, and I’d be like, ‘Maybe we should start with a job. Maybe we should just come up with big-picture goals, reverse-engineer and figure out what entry-level job will get you on a path to achieving those goals.’ I started coming up with different ideas of where they could work to start shadowing business owners and other people in the industry they wanted to be in.”

A Second Chance for Jose

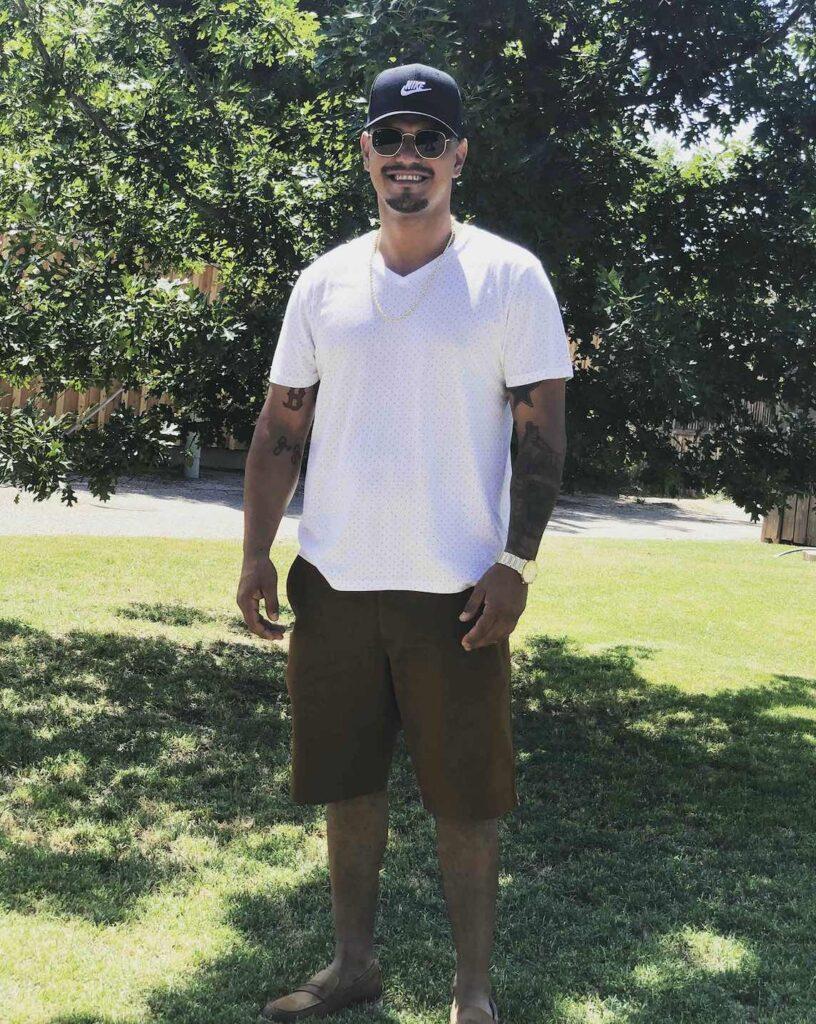

One such person was Jose Muñoz, 35, who recently had been released from a three-year turn in prison for felony possession of a controlled substance when his and Garcia’s paths crossed in 2016. By then, Cornbread Hustle (the name is derived from the prison movie Life starring Eddie Murphy and Martin Lawrence) was an “official” business.

When someone believes in you, it makes you work harder. I didn’t want to disappoint her, and I didn’t want to lose the opportunity.”—Jose Muñoz, Cornbread Hustle client

“We had lunch,” Muñoz remembers. “I told her I wanted to be a web developer, and she asked, ‘Do you have any experience?’ I said, ‘No.’ She said, ‘Why do you want to do this?’ I answered, ‘I want to make some money. I feel like I can learn anything if I put my mind to it.’ She told me she’d see what she could do to help me.”

Muñoz didn’t think much would come from the lunch and was somewhat stunned when he heard from Garcia the very next day.

“She called and said, ‘Hey, I’ve got this guy who teaches people how to develop apps. He said he’d be willing to teach you.’ I got a laptop, and the next thing you know I’m learning how to develop apps,” Muñoz says. “That was just because she believed in me and put her name on the line for me. When someone believes in you, it makes you work harder. I didn’t want to disappoint her, and I didn’t want to lose the opportunity.”

I never thought I’d be where I’m at today. …As a boy out of a small town in west Texas, I had never seen anything outside of there. …My company got me an apartment right by the river. When I’m walking at night, I’m like, ‘Wow.’ I can remember my prison cell, and now I’m looking at a river.”—Jose Muñoz

The Deeper She Sank

All the while, however, things weren’t looking up in Garcia’s own life. The higher she lifted others, the deeper she sank. She continued her work-hard-and-party-hard ways throughout that early period of Cornbread Hustle, the irony of which isn’t lost on her today. Says Garcia, “Here I was, helping people find jobs after they got out of prison and thinking I was being a good leader. But I wasn’t in reality, because I was struggling behind closed doors.”

To me, drinking alcohol every day and doing cocaine here and there to keep the party going or get up the next morning was just part of being an entrepreneur.”—Cheri Garcia

Everything came to a head in December 2017 when Garcia was slapped with a DWI: “I’m like, ‘Wow, so I’m the founder of a second chance staffing agency, and I’m in the back of a cop car.’” Yet even then, she couldn’t bring herself to slow down and seek help.

“I didn’t want to surrender to having a problem and give up cocktail hour because I didn’t understand how in the world I would be a successful businesswoman and not be able to have a drink,” she says. “To me, success and alcohol went hand in hand. I had a Wolf of Wall Street mentality where you’re not going to be successful if you can’t party hard.”

By December of the next year, she no longer could hurtle into the future like a blur. She was tired. Bone-tired.

“I Think I’m Done Drinking”

“I woke up on Christmas morning and said, ‘I think I’m done drinking,’” she remembers. “Then a couple weeks went by, and I was like, ‘I think I said I didn’t want to drink, but now I kind of want to.’ Instead, I went to church, even though I wasn’t much of a believer. I was lucky enough to have a spiritual experience two weeks into trying to quit drinking. I was basically told by God that it’s time to quit drinking. I cried. I didn’t like that, but now I had a higher power. At about five months sober, I got into a recovery program. I learned to work a program—fellowship, community, connections.”

Not coincidentally, Cornbread Hustle began to flourish as never before. On that bleak Christmas morning in 2018, she says the business was about $3,000 in the hole; now it’s on a run rate of about $2.1 million a year. That translates to a lot of second chances for folks who truly want one.

Though Garcia still moves pretty quick, she has gone to great lengths to bring something to her life that always had eluded her: calm, composure. Each of her five internal employees is in recovery, and she even has a guide, or what she calls a resilience advocate, on staff to make sure things stay that way.

“Being the founder of this company, I’m able to set the tone,” she says. “I’m able to say no alcohol or happy hours. I’m able to make it mandatory that we have recovery meetings at the office. What better life could I choose for someone who’s in recovery?”

I was basically told by God that it’s time to quit drinking. I cried. I didn’t like that, but now I had a higher power. At about five months sober, I dragged myself into the rooms of AA. I learned to work a program—fellowship, community, connections.”—Cheri Garcia

The culture of Cornbread Hustle is reflected in Muñoz, who has surpassed his wildest dreams. Now a project manager for a construction company thanks to his own determination and the placement savvy of Cornbread Hustle, he’s making a better-than-good living. But that’s just the half of it.

“I never thought I’d be where I’m at today,” Muñoz says. “I get goose bumps just saying that. As a boy out of a small town in west Texas, I had never seen anything outside of there. But with this company, I get to travel. I’ve been to New Orleans; I got to live there for two years. Now I’m in Knoxville, Tenn. My company got me an apartment right by the river. When I’m walking at night, I’m like, ‘Wow.’ I can remember my prison cell, and now I’m looking at a river.”

Meanwhile back in Dallas, Garcia finally has made sense of it all.

“It blows my mind,” she says. “It feels like I don’t even work hard to keep this business going. It just happened. And all it took was putting my recovery first.”

Photo: Kelly Sikkema