Plus: “Secret shoppers” expose shortfalls in MAT access, and troubling new data on prescription opioids

By Mark Mravic

Can more powerful and specific messaging on beer, wine and liquor packaging cut down on alcohol consumption and its associated ills? Two public health experts argue that the current warning label—essentially unchanged in more than 30 years—is outdated and ineffective, and that, in the face of the alcohol industry’s advertising onslaught, consumers deserve a truer message about alcohol’s very real health risks.

Also this week, “secret shoppers” who set out to test the availability of buprenorphine and methadone at federally funded treatment programs find access far less than reported, and a new study on the risks of opioid misuse among prescribed patients.

From The New England Journal of Medicine:

A Call for Serious Updating of Alcohol Warning Labels

In 1965, the U.S. began requiring warning labels on cigarettes. The early messages, including the longstanding, “The Surgeon General Has Determined That Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous to Your Health,” were generally ambiguous and ineffective. In the 1980s, Congress finally got serious—and so did the labels. New warnings introduced that decade spelled out specifically that smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, pregnancy complications and fetal injury and carries other real dangers. Now in a column in The New England Journal of Medicine, two public health specialists, Anna H. Grummon, PhD, of Harvard, and Marissa G. Hall, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, are calling for similarly serious and specific warnings for alcohol.

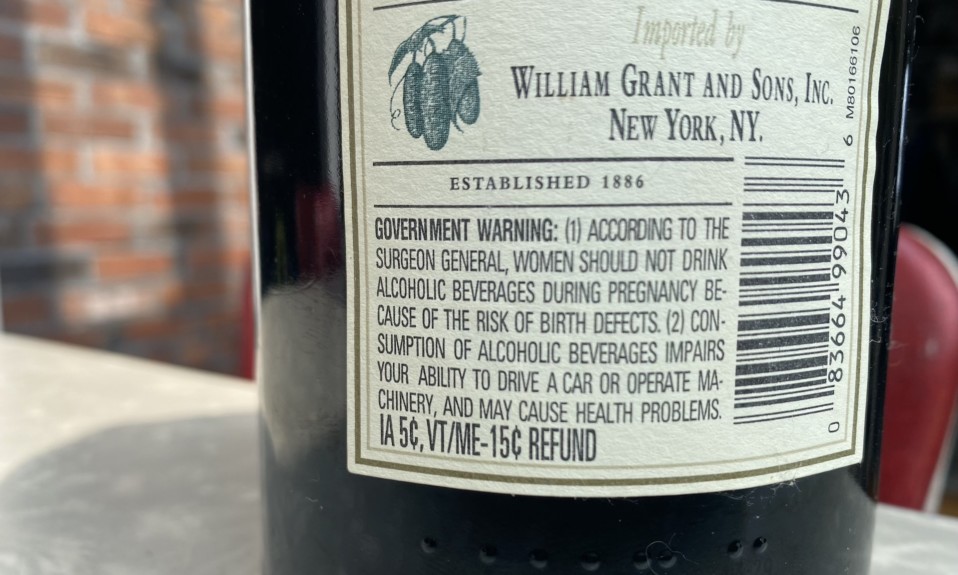

In the U.S., the warning label for beer, wine and hard liquor has been unchanged since its introduction more than three decades ago. It carries two messages—that women should not drink during pregnancy, and that alcohol impairs the ability to drive and to operate heavy machinery “and may cause health problems.” The language, Grummon and Hall say, “is so understated that it borders on being misleading” and reflects “outdated science regarding alcohol’s harms.” Since the introduction of the labels in 1989, they note, alcohol has been recognized as a group 1 carcinogen and has been linked to a wide range of diseases, including liver disease, pancreatitis and heart conditions. The authors contend that consumers are generally ignorant of such dangers, pointing to a study in which 70% of U.S. adults were unaware of alcohol’s cancer links. The labels are also ineffectively designed, they say, with small type, poor positioning and no imagery.

So what should a new label look like? One potential message they propose—in large white lettering on a black background, with a bold yellow warning image—is the simple yet direct: “Alcohol can cause cancer including breast, colon, stomach cancer.”

“New alcohol warnings could empower consumers to make more informed decisions and reduce alcohol related harms.”

—Anna Grummon and Marissa Hall

Grummon and Hall acknowledge the “information asymmetry” around booze in the U.S., where the alcohol industry spends more than $1 billion a year on marketing its products and would surely push back against efforts to better inform consumers of the risks. But the authors point to a study in Canada’s Yukon Territory that recorded a 6% to 10% decline in alcohol sales when strong warning language was temporarily introduced. “Given the high burden of alcohol-related harm in the United States,” they write, “a reduction of this size in alcohol consumption could have meaningful population health benefits.”

The authors go on to conclude, “Alcohol consumption and its associated harms are reaching a crisis point in the United States. Evidence suggests that new alcohol warnings could empower consumers to make more informed decisions and reduce alcohol-related harm. We believe Americans deserve the opportunity to make well-informed decisions about their alcohol consumption.”

From the Addiction Technology Transfer Network:

“Secret Shopper” Studies Show Continuing Shortfalls in MAT Access

Over the past five years, the federal government has more than doubled its investment in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment. In parallel, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has dramatically ramped up funding for Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs), which are seen as a critical piece of the community-based treatment puzzle. That windfall of funding led Ned Presnall, a treatment provider in St. Louis, to collaborate with researchers from St. Louis (Mo.) University and answer a simple question: “Has SAMHSA’s unprecedented investment in SUD treatment and CCBHCs led to widespread access to buprenorphine and methadone for persons with OUD [opioid use disorder]?”

“The lived experience of OUD patients seeking treatment is considerably less optimistic than the agency-level reports.”

—Ned Presnall

The researchers set up two “secret shopper” studies to test access under real-world conditions for people seeking medication-assisted treatment (MAT). In each of the studies, a caller would pose as a family member of someone seeking SUD treatment and ask about the availability of buprenorphine and methadone at a particular facility or program. The results revealed a wide gap between the expectations for these facilities and what’s actually happening on the ground. Surveying 520 publicly funded SUD treatment programs, the researchers found that only 26% offered buprenorphine and just 6% would make a prescription available on the first visit. The numbers were equally paltry for CCBHCs: Of the 257 that were contacted, 34% offered buprenorphine and methadone, and just 3% said a patient could see a MAT provider on their first visit.

Summarizing the studies for SAMHSA’s Addiction Technology Transfer Network, Pensall had two key takeaways:

- “The lived experience of OUD patients seeking treatment is considerably less optimistic than the agency-level reports. Buprenorphine availability is over-reported, and there exist significant barriers between availability and access”

- “The massive investment in OUD treatment delivery since 2016 has not led to widespread buprenorphine and methadone availability”

The main issue, he argues, is that most federal funding for OUD treatment has come in the form of non-competitive, unrestricted block grants to state agencies, which then contract with treatment providers or local entities—many of them the same ones that failed to adopt MAT in previous years. And he notes that CCBHCs, while strongly encouraged to provide methadone and buprenorphine treatment, are not required to do so to receive federal money. The better model, Pensall suggests, is SAMHSA’s smaller but targeted grant program called Medication Assisted Treatment—Prescription Drug and Opioid Addiction (MAT-PDOA). Grants in that program have clear and measurable requirements to start patients on MAT and retain them in treatment.

“Now that Congress has begun to appropriate funds to address the opioid crisis, it must hold SAMHSA, state [agencies] and treatment providers accountable for making buprenorphine and methadone universally accessible,” Pensall writes. “This goal will likely require stricter grant requirements and increased investment in medical settings such as federally qualified health centers and rural health clinics—agencies with the medical workforce necessary to make buprenorphine and methadone universally available to persons with OUD.”

From PLOS Digital Health:

A Troubling Percentage of New Prescription Opioid Users Develop Chronic Use

A new study from Stanford University and healthcare tech company Gainwell found that nearly 30% of Medicaid patients who were given their first-ever opioid prescription following surgery developed a dependence on the drug—a troubling result that the authors say calls for reconsidering opioid prescribing guidance and developing technology to better identify at-risk patients.

Researchers analyzed claims data from 2015 to 2019 for 180,000 previously opioid-naïve Medicaid patients, and defined the progression to chronic opioid use (COU) as receiving at least one additional opioid prescription three to nine months after the initial prescription. Of that cohort of 180,000 patients, 53,820 developed COU, with risk factors for dependence including the quantity, strength and length of the initial prescription. The type of opioid mattered, too: Higher proportions of tramadol—typically seen as a “safe” opioid—and long-acting oxycodone in prescriptions also increased the dependency risk, according to the researchers.

Part of the goal of the study was to develop machine-learning algorithms that can use claims data to help identify patients who might be at greater danger of developing opioid dependence after surgery, especially among the more vulnerable Medicaid population, and to adjust pain management strategies to lower the risk.

“The U.S. is being ravaged by an opioid epidemic that costs us tens of thousands of lives and billions of dollars each year,” said lead author Tina Hernandez-Boussard, PhD, MPH, associate professor at Stanford’s School of Medicine, in a release. “Data holds the key to solving the opioid epidemic. This study should provide some pause to doctors who prescribe only opioids as a first-line treatment for pain rather than non-opioid pain medications.”