The notorious “party” drug has a complicated history and complex recreational profile—but it shows major promise in treating trauma and addiction

By Mark Mravic

MDMA occupies an unusual position in the landscape of substance use. Recreationally, under the street names ecstasy (usually the pill form) and Molly (powder or crystal), it’s seen as a party drug, with a reputation for being comparatively “safe” and non-addictive—despite significant adverse effects and even deaths associated with its use. Taken recreationally, it creates a sense of euphoria and well-being, as well as feelings of closeness and bonding with others.

As a synthetic drug related to amphetamine, MDMA also has stimulant effects—hence its propensity as a dance drug. It’s often grouped with LSD, mushrooms and ketamine as a psychedelic, but its hallucinatory effects are mild in comparison.

On the therapeutic side, MDMA has gained traction in recent years as a promising treatment for a range of mental health conditions, notably post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Some users insist on a distinction between MDMA, ecstasy and Molly, though that may have something to do with the widespread adulteration of the substances sold as MDMA. Because the current market for the drug is illegal and unregulated, what passes for MDMA often contains other substances as well or no MDMA at all.

The Long, Strange History of MDMA

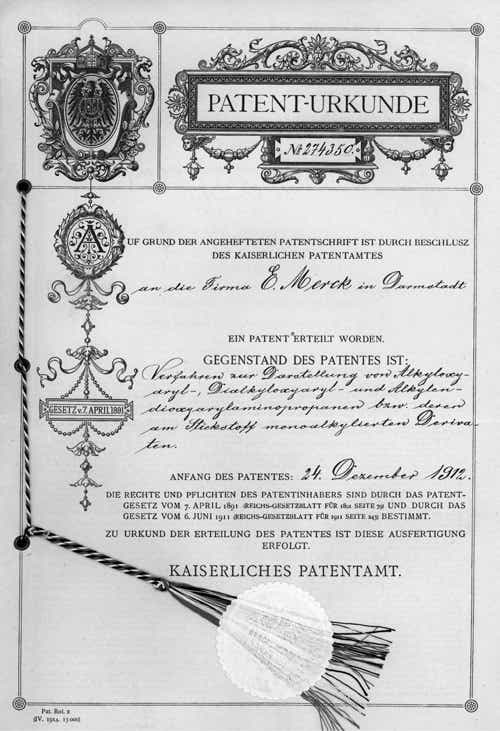

MDMA—the chemical name is 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine—was first synthesized in Germany in 1912 by Merck as it was looking into blood-clotting medication. The company, however, didn’t pursue clinical research or pharmacological applications, and the first studies in animals didn’t take place until 1927. (The myth that German scientists “invented ecstasy” as an appetite suppressant for soldiers in the First World War was so widespread that Merck commissioned its own historians to explore its archives and uncover the truth.) MDMA next emerged—surreptitiously—in the early 1950s, when the U.S. military and the CIA began animal experiments with it as part a secret program looking into drugs for behavior modification.

MDMA emerged from this shadow world only in 1960, when a Polish scientific journal published its chemical formula. Anecdotal reports of its recreational use began to surface in the following years, and in 1970 the first MDMA tablets were seized by authorities in Chicago. MDMA’s therapeutic use was kickstarted in the ’70s when chemist Alexander Shulgin—sometimes called “the Godfather of Ecstasy”—synthesized MDMA and self-administered the drug. “It was not a psychedelic in the visual or interpretative sense,” Shulgin wrote in his memoir, “but the lightness and warmth of the psychedelic was present and quite remarkable.” He dubbed MDMA the “low-calorie Martini.”

Shulgin subsequently introduced MDMA—then called “Adam”—to San Francisco psychotherapist Leo Zeff, who became a pied piper of sorts, influencing hundreds of psychologists and therapists across the country to incorporate the then-legal drug into their treatments for disorders such as anxiety, trauma and couples therapy. Not surprisingly, word of MDMA’s mood-altering effects spread, and in the early ’80s it became popular recreationally among certain discrete groups—college students, yuppies, gay men and New Age adherents. MDMA also spread to Europe around that time, insinuating itself into the burgeoning electronic dance music scene in Spain and the U.K.

It was then that MDMA ran smack dab into the newly launched War on Drugs. In response to its growing street presence and the absence of established clinical research into its therapeutic value, in 1985 the U.S. issued an emergency authorization classifying MDMA as a Schedule I drug, meaning it had no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. The status was made official in 1988 despite opposition from some in the therapeutic community. Overseas, the U.K. cracked down in 1990 after a number of high-profile ecstasy-related deaths.

Despite being driven underground—or maybe because of it—MDMA’s recreational use grew rapidly, creating a huge illicit and unregulated international market in production and trafficking. By the mid-’90s, ecstasy had become engrained in certain youth cultures in the U.S. and U.K. Its depiction in movies and music—in 2012, Madonna released her MDNA album—spurred curiosity and only further drove its use.

The Extent of MDMA Use in the U.S.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), MDMA is predominantly used in the U.S. by males between the ages of 18 and 25. LGBT men and women are more likely to have reported ecstasy use in the past 30 days. Overall, according to the 2020 National Survey of Drug Use and Health:

- 7.4% of people over the age of 12 reported using ecstasy sometime in their life

- 0.9% of those over the age of 12 reported ecstasy use in the past year and 0.2% in the past month. Those numbers are roughly on a par with LSD use and about a third that of cocaine

The annual Monitoring the Future survey reveals trends in substance use among high-school-age children in the U.S. Among the findings:

- MDMA use among high school seniors peaked in 2001 at 9.2%, before stabilizing at 4% to 5% annually in the mid-2000s. The decline since 2011, when prevalence was 5.3%, has been steady.

- MDMA use among high school students has dropped by half in the two years of the COVID pandemic. In 2019, 2.2% of 12th-graders, 1.7% of 10th-graders and 1.1% of 8th-graders reported using MDMA. In 2021, those numbers dropped to 1.1%, 0.7% and 0.6%, respectively.

How MDMA Works

MDMA primarily functions by releasing the neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine and/or blocking their reuptake. The effects begin about 30 to 60 minutes after taking a dose and typically last for three to six hours. Many recreational users will take additional doses to extend the effects.

Because of the complexity of the central nervous system’s response to MDMA, effects from the same dosage can vary widely from user to user. Effects also are strongly influenced by the concentration of actual MDMA in a dose, the potential adulteration of pills and powder by other compounds, and the extremely common use of a wide range of other substances alongside MDMA.

Among the short-term effects of MDMA are:

- Enhanced sense of well-being

- Increased extroversion

- Emotional warmth

- Empathy toward others

- Willingness to discuss emotionally charged memories

- Enhanced sensory perception

MDMA also influences the body’s levels of oxytocin, sometimes called “the love hormone” because it enhances feelings of emotional connection and empathy. In therapeutic use, researchers believe that effect accounts for MDMA’s help in building a strong therapeutic alliance, which is critical to MDMA-assisted therapy.

Of course, there’s no upside without a downside, and MDMA’s short-term adverse effects can include:

- Involuntary jaw clenching and teeth grinding

- Lack of appetite

- Mild detachment from oneself (depersonalization)

- Illogical or disorganized thoughts

- Restless legs

- Nausea

- Hot flashes or chills

- Headache

- Sweating

- Muscle or joint stiffness

The Dangers of MDMA

Strict overdoses—that is, someone dying after taking more than a “normal” amount of MDMA—are rare, but they do happen. For instance, in 2017 a law student in the U.K. attending a music festival died after taking 2.3 grams of MDMA—some 20 times the “normal” recreational dose of 75 to 125 mg. Anything above 1.8 grams is considered toxic, and beyond that can be fatal.

Most MDMA-related deaths, however, occur when an individual takes a “normal” dose. (DanceSafe.org, a harm reduction advocacy group, goes so far as to say, “Stop Calling Them Overdoses.”) The dangers increase with inexperienced users, lack of on-site harm reduction resources and use in combination with other drugs.

A U.K. study based on coroner reports and crime data estimated a death rate of 1.75 out of every 100,000 users when MDMA was the sole drug reported, but substantially higher—10.89 per 100,000—when taken alongside other drugs. A study in Australia reported similar results, with MDMA the sole cause in 15% of deaths in which it was identified in mortality reports, with psychostimulants (54%), alcohol (43%), opioids (30%), cannabis (25%) and benzodiazepenes (23%) also involved.

In the U.S., a 2021 study originally intended to evaluate MDMA-related deaths from the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) noted that there were so few cases of sole ingestion of MDMA in the data—just two among nearly 14 million records dating to 2003—that the aim of the research had to be revised to look at MDMA-related deaths when taken with other drugs.

That study found that the most common drugs reported alongside MDMA in FAERS were opioids, benzodiazepines, amphetamines and stimulants, MDMA metabolites such as MDA, as well as cannabinoids, cocaine and antidepressants. But just how those drugs interact with MDMA to cause emergencies and deaths is extremely difficult to pin down. The study’s authors note they were limited because FAERS reporting is voluntary and observational (rather than clinical), and lacks information on demographics, dosing and drug purity.

In other words, hard data on MDMA’s mortality risk is difficult to come by and complicated by the fact that the drug is almost always used recreationally in conjunction with other substances. “It should be highlighted that MDMA used by itself was very uncommon in FAERS reports,” the researchers noted, “speaking to the rarity of severe adverse reactions when taken alone.”

Common Adverse Effects of MDMA

The most common cause of MDMA-related emergencies and deaths is hyperthermia, or heatstroke. A normal dose of MDMA raises body temperature by about one degree and inhibits the body’s ability to regulate temperature. Considering that ecstasy is often taken in hot, crowded environments like dance clubs and involves aerobic exertion, that’s a recipe for trouble. In 2014, for instance, more than 100 people who attended a series of North American concerts by Swedish DJ Avicii were hospitalized for heatstroke, and many were found to have taken MDMA. Authorities blamed the conditions in the venues and also noted that alcohol, which can exacerbate dehydration, was a contributing factor in many of the cases. As DanceSafe puts it, “MDMA is very often a contributing factor but rarely the sole factor in heatstroke emergencies.”

Compounding, or maybe confusing, MDMA’s danger is that the drug itself causes the body to retain water. Given MDMA’s overheating potential, ecstasy users in the past were instructed to consume plenty of water when taking the drug. But because of its water-retention effects, drinking too much water while on ecstasy can bring on hyponatremia—or water-toxicity, a potentially fatal condition in which the concentration of sodium in the blood becomes diluted to dangerously low levels. Women are at greater risk due to estrogen’s effects on cell regulation. One study on MDMA and water toxicity referred to a “perfect storm” of ecstasy-induced effects on water balance. Another study concluded that “otherwise healthy young females are at risk of a potentially fatal complication that could easily go unrecognized and untreated.” It urged that emergency personnel at raves and concerts be trained to recognize the symptoms of water toxicity—headache, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, confusion, altered mental status, or seizure—and be prepared to treat it with a quick infusion of sodium.

In addition, MDMA causes an increase in heart rate and blood pressure that puts users with cardiac issues at risk. Indeed, when journalist Michael Pollan set out to experiment with psychedelics for his book How to Change Your Mind, his cardiologist told him to leave MDMA out of his experiments.

In rare cases, often involving high doses or chronic use, users can develop seratonin syndrome, the build-up of dangerously high levels of serotonin in the body. Severe symptoms include muscle rigidity and seizures.

One of the most notorious and widely reported effects of MDMA is the “hangover,” often called “Blue Monday” or even “Suicide Tuesday”—when effects such as depression, fatigue and sleeplessness set in during the days following MDMA use, as the body attempts to replenish serotonin levels. One study of MDMA in a clinical context, however, found that the effect doesn’t occur after controlled medical use—indeed, participants reported something of an “afterglow.” That suggests the hangover may be a vestige of polydrug use, lack of sleep or other factors.

Given MDMA’s potentially dangerous effects, advocates have strongly pushed for harm reduction measures at large music events, raves and other activities where ecstasy is expected to be used. Those measures include reducing temperatures inside the venue, providing chill rooms and making Gatorade or other drinks with electrolytes readily available. Harm reduction groups also recommend providing drug-checking, making educational materials available and having medical staff on-site who can recognize and treat heatstroke, water imbalance and other adverse effects.

Is It Even MDMA?

A considerable danger in MDMA use is that pills or powder sold as MDMA, ecstasy or Molly are often cut with other substances unknown to the user or contain something else entirely. In addition, the amount of MDMA in a single pill can vary widely. Last year a tablet circulating in the U.K. called “The Punisher”—bearing the logo of the Marvel character of the same name—was found to contain 477mg of MDMA, four to five times a regular dose. A wheelchair-bound 19-year-old in Wales died in June 2021 after taking two of the pills. Online resources such as PillReports and The Trip Report have arisen in recent years to warn of high-dose and adulterated tablets.

Among the substances regularly cut with MDMA, as reported on the drug-checking site drugsdata.org, are:

- MDA (“Sally”)

- ketamine

- methamphetamine

- cocaine

- “bath salts”

- caffeine

In 2021, 16% of drugs sold as MDMA and tested on drugsdata.org contained no MDMA at all. Some were a single substance, such as MDA, ketamine, methamphetamine or a “bath salt”; others were combinations of those and other substances. A pill sold in Chicago as ecstasy and called “Fish” contained seven parts caffeine and one part methamphetamine.

Contaminants and misidentified drugs, of course, can cause unexpected effects or lead a user to take additional doses if the drug feels weaker or different. They can also complicate treatment by medical personnel in the event of an adverse incident. In November 2021, a Canadian medical student was sentenced to a year in prison for providing a Virginia woman with what he thought was MDMA but was actually MDA; she died after taking the drug.

Addiction and Long-Term Effects

Research isn’t conclusive as to whether MDMA is addictive, though it does influence some of the same brain mechanisms associated with addiction in other drugs. Several studies of heavy MDMA users showed that they met diagnostic criteria for dependence and abuse, such as continuing to use despite knowing the physiological and psychological harms, as well as tolerance and withdrawal. How much of that is due to behavioral or psychological factors, as opposed to physiological processes that cause addiction in other addictive drugs, has been difficult to determine.

Research involving regular MDMA users has also shown some level of craving, though not as intense as other drugs. Studies have shown that animals will self-administer MDMA, a sign of addictiveness, though, again, the level of self-administration was less than in other drugs, such as cocaine. “Studies examining the structure of dependence upon ecstasy suggest it may be different from drugs such as alcohol, methamphetamine and opioids,” a 2009 report noted. “Regardless of the nature of any dependence syndrome, however, there is evidence to suggest that a minority of ecstasy users become concerned about their use and seek treatment.”

As to long-term effects, studies of heavy recreational MDMA users have shown evidence of memory impairment, impulsiveness, depression and sleep disturbance. As with other aspects of MDMA, research into its recreational addictiveness and long-term effects varies widely depending on populations studied and measures used. Importantly, however, users who have been given MDMA in clinical settings have not shown signs of addiction or illicit use outside of treatment.

MDMA’s Therapeutic Potential

Recreational use aside, MDMA has shown itself in recent years to be a promising medication in a controlled clinical setting for a range of therapeutic applications related to trauma and substance use disorder. As Ben Sessa, MD, senior research fellow at Imperial College London, told The Guardian, “MDMA selectively impairs the fear response. It allows recall of painful memories without being overwhelmed.” Sessa, who is also chief medical officer at Awakn, a UK R&D company that focuses on psychedelic treatments, added, “MDMA psychotherapy gives you the opportunity to tackle rigidly held personal narratives that are based on early trauma. It’s the perfect drug for trauma-focused psychotherapy.”

In a 2014 study of MDMA’s effects on recollecting strong memories, participants reported experiencing their favorite memories as more vivid, intense and positive after MDMA, and their worst memories as significantly less negative. “The bad memories were less salient,” one subject said, “and I thought about them in a matter-of-fact way.” Another subject said: “When I reached back for the bad memories, they did not seem as bad. In fact, I saw them as fatalistic necessities for the occurrence of later good events.”

The Awakn website notes: “It is believed that MDMA suppresses chemicals released in response to negative stimuli (such as revisiting trauma), thereby allowing clients to engage these painful memories without being overwhelmed. It also creates temporary changes in brain functioning that support the learning of new behavioural responses.”

But taking the drug on its own won’t necessarily create those responses. Psychotherapy with trained counselors is an integral aspect of MDMA treatment. Unlike other trauma therapy, such as prolonged exposure, patients aren’t instructed to confront painful memories directly. Instead, the daylong therapy sessions with MDMA are more free-flowing, with counselors creating a sense of trust and supporting the participants’ unfolding experience.

MDMA for PTSD

One of the most prominent therapeutic MDMA studies involves patients suffering from severe PTSD who have not responded to other treatment. At the forefront of this research is the Boston-based Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). In 2017, after MAPS’ Phase 2 clinical studies showed MDMA-assisted treatment to be safe and potentially effective, the FDA designated it as a breakthrough therapy for PTSD.

MAPS’ first Phase 3 trial, which was published last May in Nature, involved 90 subjects who suffered PTSD from military experiences and child abuse. Participants underwent three 90-minute preparatory therapy sessions, then three eight-hour guided sessions with MDMA (or a placebo), spaced a month apart. Nine 90-minute sessions followed, to consolidate and integrate the experience. The results were eye-opening. Two months after treatment, 67% of participants who received MDMA-assisted therapy no longer qualified for a diagnosis of PTSD, compared to 32% in the control group.

“It is intriguing to speculate that the pharmacological properties of MDMA, when combined with therapy, may produce a ‘window of tolerance,’ in which participants are able to revisit and process traumatic content without becoming overwhelmed or encumbered by hyperarousal and dissociative symptoms,” the study’s authors wrote. “MDMA-assisted therapy may facilitate recall of negative or threatening memories with greater self-compassion and less PTSD-related shame and anger.”

And there’s a reason MAPS’ research and other studies of MDMA and trauma have involved military veterans. “We had to choose which psychedelic and which patient population would be most likely to be successful from a political perspective,” MAPS founder Rick Doblin, PhD, told Boston magazine. “The choice of working with PTSD and MDMA with a lot of veterans has been fundamental to our success. It’s insulated us from this ‘psychedelics, left-wing, counterculture hippies’ thing that we have taken 50 years as a culture to get past.”

MAPS is now conducting its second Phase 3 study, looking to confirm its previous results. If successful, the FDA could approve MDMA-assisted PTSD therapy as soon as next year.

MDMA for Alcoholism

Additional promising research on MDMA involves treating alcohol use disorder (AUD). Last year at Awakn, Sessa and his U.K. team concluded a Phase 2 study, which found the treatment safe and tolerated. As with PTSD, the AUD treatment involves preparatory psychotherapy, then several daylong therapy sessions combined with MDMA, as well as follow-up therapy without the drug.

Results among the small cohort (14 subjects) suggest MDMA treatment may have significant long-term effectiveness in reducing alcohol consumption. In the study, three-quarters of subjects who underwent MDMA-assisted therapy showed continuing improvement after nine months, compared to 21% in the control group that received standard AUD treatment. Alcohol consumption among the MDMA group dropped dramatically—from an average of 130.6 units per week per subject to 18.7 units (a standard glass of wine is about two units). Nine months after the trial, only three of the 14 participants were drinking more than 14 units a week. In comparison, relapse rates for AUD under standard treatment are about 60% after a year.

Additional studies are ongoing into MDMA’s potential for eating disorders, social anxiety, couples counseling and fear among people with advanced-stage cancer and other life-threatening illnesses.

The Future of MDMA

MAPS researchers argue that trauma therapy could be more critical than ever in the coming years, as people process the pain and disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We may soon be confronted with the potentially enormous economic and social repercussions of PTSD, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic,” the Phase 3 study noted. “Overwhelmingly high rates of psychological and mental health impairment could be with us for years to come and are likely to impart a considerable emotional and economic burden. Novel PTSD therapeutics are desperately needed, especially for those for whom comorbidities confer treatment resistance.”

Thanks to the success of these preliminary studies, MDMA-assisted therapy may soon be an accepted treatment for a wide range of mental health issues. Part of that will require overcoming a longstanding aversion to psychedelics, and distinguishing therapeutic MDMA from its unregulated and potentially dangerous recreational use. “If there was a craze of people going around abusing cancer chemotherapy drugs, you wouldn’t then think: ‘Oh well, it’s not safe to take cancer chemotherapy when doctors give it to you,’” Sessa told The Guardian. “Scientists know it’s not dangerous.”

Doblin, the MAPS founder, would like to see MDMA accepted, regulated and incorporated into the mainstream. “I think we all have subclinical levels of trauma or depression just by paying attention to the newspaper,” he said in the Boston magazine interview. “The world is running off a cliff, and we need more people to process their trauma and not be run by fears and anxieties and hatred… . ”

Eventually, Doblin wants MDMA and other psychedelics to be licensed for what he characterizes as “adult” (as opposed to “recreational”) use. “Think of licensed legalization as a little bit like drivers’ education,” he says. “You go to a psychedelic clinic, you learn about what it is, you get permission, you get a license, and you can go buy it.” And what about a freakout? Simple. If “you decide that you are God and you take off your clothes and you run down the street preaching to everybody and the police bust you,” Doblin says, “you lose your license.”

Top photo: Shutterstock; concert photo: Mika Rekar