In a compelling new book, Dave Kindred explores the odyssey of Jared to learn why he was lost to alcoholism

By Jason Langendorf

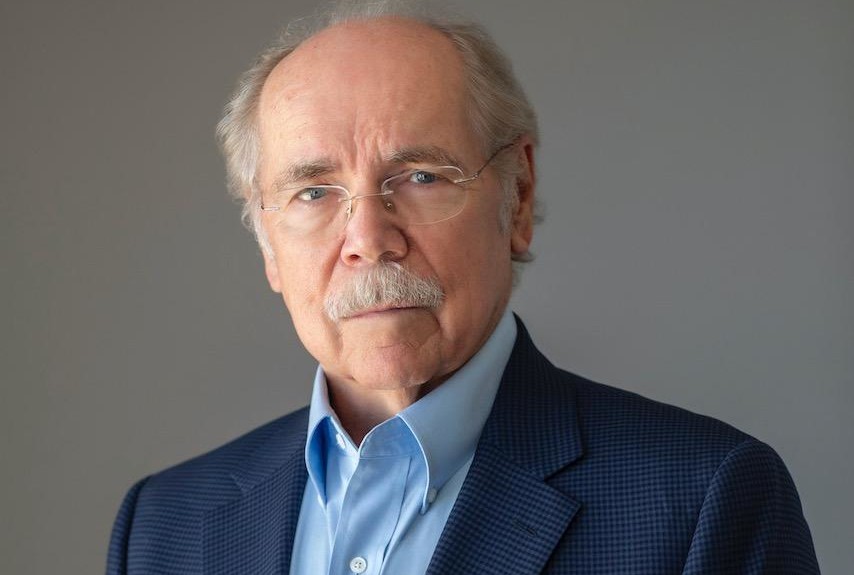

March 11, 2021Dave Kindred has spent over half a century telling poignant and spellbinding sports stories for outlets as wide-ranging as the Louisville Courier-Journal, The Washington Post and Sporting News, as well as authoring several acclaimed books. He’s also passing along his wisdom to the next generations of sports journalists as a professor at Illinois Wesleyan University (his alma mater) and Bradley University.

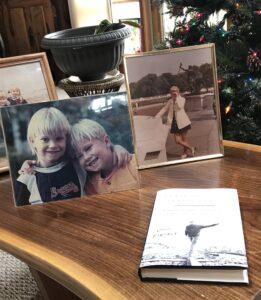

But in his latest book, Leave Out the Tragic Parts, Kindred turns his professional attention from ball fields and athletes to home and his own family—specifically, his grandson Jared’s painful struggles with addiction. Kindred blends reporting and memoir in an effort to make sense of Jared’s journey from happy youth to an itinerant adulthood, alcohol dependency and, ultimately, his death in 2014 at age 25.

Kindred spoke to TreatmentMagazine.com about the book, how he has dealt with the loss and what he has learned from the experience.

My wife and I felt helpless, just helpless. I think parents undoubtedly feel helpless, too. It’s a matter of education: People have to understand what addiction is.”—Dave Kindred, author of “Leave Out the Tragic Parts”

Q: You took a particular approach to this book. Was it important for you to report it out rather than make the book only a memoir of your memories and thoughts of Jared?

A: I had to know what happened. I had to know. Jared disappeared from my life, basically. When he was 18, out of high school, he was gone. I saw him maybe two or three times in the last seven years of his life. I was in contact with him, and his mother kept me in contact with him, but I wasn’t around him. So when he died, when it actually happened, I had to know the events that led to it. I had to know the trials and tribulations. So the reporter in me was able to do that. I was able to hear the hard stories and hear the good stories. I was able, then, to do a memoir that was at least partly an essay on grief and love, and much more a reporter’s journey into a place he’d never been, to find out what happened.

Q: Who was Jared—the person you knew and then the person you learned about through your reporting?

A: The first thing to say is that I would not have written the book if I had discovered in the reporting that Jared was something other than the Jared I knew as a child living in my house—living next door to me, the Jared I told stories to, the Jared who was a sweetheart as a kid growing up. That’s the Jared I knew. If I had gone on the road and talked to all his friends and discovered he was some kind of bum, that he stole purses off little old ladies or something, I would not have written the book.

My thesis in the book—because I cut Jared every break, as I think any grandfather would do—is that the addiction chose him, he didn’t choose addiction. Addiction happens to different people for different reasons.”—Dave Kindred

I didn’t know what I was going to find, but I discovered that everyone he touched, everyone he traveled with, loved him. He was the same kind of happy sweetheart on the road that he had been when I knew him as a child. He was kind of your normal kid. He wasn’t a philosophical wanderer, like the kid in Into the Wild. He was just a boy having fun. How he became that person on the road was what I tried to explain in the book. There are moments of great joy in the book; there’s lots of fun in the book. That leads to the darkness, inevitably. But the Jared I knew as a kid growing up—the sweetheart, the Little League baseball player, the 2-year-old who would sit on my lap and listen to my stories—was still the grown-up version of that. So I was very happy to discover that.

Q: Did you think Jared’s personality—carefree, innocent—made it difficult for him to fit into the world or had anything to do with leading him to his troubles with addiction?

A: Well, I think that’s an unanswerable question. I think all the kids I met on the road or who I talked to about Jared are all running from something. They’re all running from some kind of pain. An administrator in Louisville told me, “We’re all alcoholics because we want to change the way we feel.” You don’t change the way you feel unless you’re unhappy with the way you feel. And I think that’s what they all were doing. They’re altering the thing that causes them pain. And by running from something, they’re also running to something—to a place where they fit in. They’re running to a place where they feel comfortable. They’re running to a place of their kind, where they’re accepted for who they are. No one is trying to change them. No one is trying to tell them they must do this. And he felt comfortable in that. Certainly you wish that he didn’t; you wish he had had the normal kid growth. That’s all we want for the people we love. But that wasn’t in the cards for him.

Q: Did Jared know how deeply his drinking was affecting him?

A: When he was 13 or 14, one day he told my wife, “Grandma, I’m an alcoholic.” And we thought, because we were ignorant, How does a13-year-old kid know anything about alcoholism, let alone announce that he’s an alcoholic? So we just ignored it, I’m afraid. If there’s one thing I learned—and it might not even be true; I still don’t know—but we should have intervened then. When he’s 13, if a kid tells you he’s an alcoholic, if he tells you he’s in trouble, there’s some reason he’s telling you. Maybe that was the first cry for help. We heard, and we didn’t even know what it was. But now I’d intervene quickly and as strongly as I could.

Q: As the grandparent of a person with addiction, what are the difficulties beyond what you just mentioned?

A: My wife and I felt helpless, just helpless. I think parents undoubtedly feel helpless, too. It’s a matter of education: People have to understand what addiction is. And by the time my wife and I understood the enormity of the problem, it was much, much too late to do anything about it. Most of what I think and know about addiction I learned just by reading David Sheff’s Clean, in which he talks about addiction as a disease, not a character flaw and not a moral failing. It’s a disease that has to be treated as a chronic disease.

For instance, Jared suffered seizures all the time. As an ignorant layman, I thought the seizures were caused by drinking too much. And, yes, sort of. But basically, the seizures are caused when the substance—in this case, alcohol—is denied to the brain. The brain has been wired to need the substance. And if it doesn’t get it, it rebels, and the seizure comes. My thesis in the book—because I cut Jared every break, as I think any grandfather would do—is that the addiction chose him, he didn’t choose addiction.

Addiction happens to different people for different reasons. Some brains are resistant, some brains are susceptible to it. His brain at 13 probably was susceptible to it. So addiction chose him, addiction owned him, addiction made his choices. Jared would not have chosen that life had he been able to choose anything else. The best illustration of that in the book comes when his mother, an amateur photographer, had an idea for a book of photography. She lives in Myrtle Beach, S.C. She would take people to the beach and have them write in the sand one word, a part of their life they would want to wash away. So when Jared was maybe 20, 21 years old, she took him to the beach. With a walking stick that he had, he wrote in the sand the word “booze.” That was as close as he ever came to acknowledging the depth of his problem. He wanted booze washed out of his life, but he couldn’t do it.

Q: Book titles often get put through the wringer. Can you explain how you arrived at yours?

A: The last time I saw Jared was in October of 2013. He was at his father’s house in Virginia. My wife and I went there to see him. We’re talking, and I had been keeping notes on his life as best I could, because I thought at some point I’m going to write something about this life that he’s leading. Of course, I was looking for the happy ending. I was looking for a time when it would all change, that this would be a phase, because I was stupid. I didn’t understand the addiction. I was waiting for a time when this would be over. So I said to him and a couple of his friends traveling with him, “I’m going to write about this, so I want you guys to remember everything. Tell me everything and make it funny.” And my son was standing there and said, “Leave out the tragic parts.” And Jared said, “Yeah, nothing tragic.” The editor of the book chose the title. He picked out that sentence the absolute first time he read the book.

Q: You’ve now written eight books. How was this one different from the others?

A: Every other book was a sports-centric book. This one has no sports in it of any kind. I’ve always written about people and ideas. But my goal with this book was, I wanted it to be as good as I could make it. Because I didn’t want to write a book that people would just toss away and say, “This is just another addiction book. There’s nothing new in here. There’s nothing that we can learn from this.” I wanted people to be able to read the book and see Jared, and see that behind the addiction there is a real person we should care about, and that we should do everything for that person that we can do, because they no longer are in charge of their life. The addiction is in charge.

There’s an underbelly of America that nobody even knows exists. Who knows how many of these kids running from pain are out there? It’s important to tell every one of [their stories] as well as you can, as a cautionary tale for other people.”—Dave Kindred

As a grandfather, I can say, as I did, a thousand times, “Jared, you gotta quit. You gotta quit drinking this stuff all the time.” He’s heard that a thousand times, and he has said a thousand times the thing that an addict will always say to you: “Yeah, I’m gonna do it, I’m gonna change, I’m better.” Jared would say, “I’m cutting down, Grandpa.” Well, no. They lie to you. Because they can’t help it. And you can’t get angry at them about it. You just despair. So that’s what I come back to: Once you recognize there’s a problem, do everything you can to help them. But know that there’s a limit. They have to do it.

Q: What was your takeaway after finishing the book? Do you have a different outlook on addiction than you did before?

A: I know more about addiction now than I ever did, for sure. Just even the mechanics of the brain, the logistics of the brain, the way the brain works, how a substance or an idea—sex, for instance—can rewire the brain to a place where it needs that substance. That idea, I never knew the physical nature of the way the brain reacts. It was not that I ever thought addiction was a moral failing. But it was like, “Just tell him to stop drinking.” Well, OK, that’s like telling the sky to stop being blue. They’re no longer in charge of the decisions.