We caught up with a treatment professional to gather some thoughts on what this solemn day means

By Jenny Diedrich

Today is International Overdose Awareness Day, and addiction treatment centers, recovery professionals and loved ones are remembering those who were lost to drug overdoses.

The global event is held each year on Aug. 31 to raise awareness around overdoses and addiction, and reduce the stigma associated with a drug-related death. International Overdose Awareness Day also is meant to acknowledge the grief of families and friends whose lives were permanently altered by fatal ODs.

Unfortunately, it’s a problem that’s only growing more tragic. More than 93,000 people in the U.S. died from drug overdoses in 2020, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an ignominious record that marked a 29% increase from the 72,151 OD deaths in 2019.

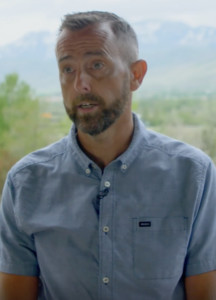

For a few insights into the subject on this important day, TreatmentMagazine.com touched base with Rich McDonald, MS, CMHC, clinical director at the Utah-based Wasatch Crest Addiction Treatment Center. Given the nature of his position, McDonald has had an up-close look at the opioid epidemic and the resulting devastation.

Q: Overdose deaths have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Why is this?

A: There’s probably an impact here that we don’t fully understand yet. Some people lost their insurance, so access to treatment may have changed. Part of it is the lack of connection with services. Isolation has really made an impact. At Wasatch Crest, our alumni program went virtual for a while, which is a huge part of what we do. Access to in-person meetings changed.

Also, when people are unemployed or working from home, the ability to use drugs without anyone questioning them can increase their use. No one is seeing you on a regular basis.

Q: Is there any positive news regarding overdose prevention?

A: There is interesting stuff going on nationally, [such as getting the overdose-reversal drug] Narcan into the hands of everyone who is willing. First responders have Narcan, and it’s available in a lot of health departments. In Utah, you can go to the county health department, and they’ll give it to you for free. That has increased access because it’s expensive at pharmacies. It’s been a big shift. Previously it was more difficult to get.

Q: How does your facility address overdose risk post-treatment?

A: Engagement with your peers in recovery post-treatment is so incredibly important. Our alumni coordinator stays connected with every client on a schedule, reaching out to them quite frequently the first year post-treatment. We do anything we can to create community. There’s no way to stay sober without a community of people around you. You can’t do it alone.

Education is critical. Everyone has heard the story about people coming to treatment, they finish and get out, use [drugs] once and pass away. Helping clients understand that risk is important.”

—Rich McDonald, Wasatch Crest Addiction Treatment Center

When you come into treatment, you’ve alienated yourself from most of the people who really care about you. Having the community that really cares about you is one more thing that you’re not willing to jeopardize by relapsing.

Education is critical. Everyone has heard the story about people coming to treatment, they finish and get out, use [drugs] once and pass away. Helping clients understand that risk is important.

Q: What else should we as a nation be focusing on to help prevent overdose deaths?

A: Giving access to treatment during incarceration and through the legal process is critical. Also funding community treatment programs—that’s one area where everyone wins.

One of the other big components is medication-assisted treatment. Vivitrol is an extended-release injection that can be taken approximately every 28 days. It’s an opioid blocker, so if someone uses, they don’t get the effects of opioids, and they also don’t get cravings. More insurance companies are willing to pay for it, and there are community resources for patients who don’t have insurance to help pay for it.

We try to get everyone who’s willing to get the injection and continue for the first 12 months of their sobriety. I’ve talked to a lot of clients who have said it was a barrier to relapse. It’s overdose protection.

Photo: Shutterstock