We spoke to Brandee Izquierdo, executive director of SAFE Project, about the importance of disposing of unused medications and about a host of other topics

By Jenny Diedrich

The recovery community sees the disposal of unused prescription drugs as one more tool in the fight against the opioid epidemic, and it is promoting its necessity during National Prescription Drug Take Back Day on Oct. 23.

Overdose rates continue to spike during the COVID-19 pandemic, with preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicating that at least 93,000 people died from a drug overdose in 2020. That’s an increase of almost 30% from 2019.

National Prescription Drug Take Back Day encourages people to properly dispose of dangerous unused and expired medications in their homes, according to Brandee Izquierdo, executive director of SAFE Project, a national nonprofit that uses a collaborative, non-partisan approach to work to end the opioid epidemic.

As part of National Prescription Drug Take Back Day—and beyond—SAFE Project and its partners are distributing free, at-home drug disposal pouches to prevent medication misuse and abuse. The pouches use activated charcoal and tap water to make unused or expired drugs inactive and safe to put in household trash. “It’s important for us to provide prevention tools that can be used on a daily basis,” Izquierdo says.

TreatmentMagazine.com recently talked with Izquierdo about her own recovery journey, her work leading SAFE Project and the importance of removing unused prescription drugs from homes.

Seventy percent of opioids that were prescribed for post-surgical use are left unused. We work with companies to provide disposal bags for prescriptions. We know … that substance use is running rampant right now.”

—Brandee Izquierdo, executive director of SAFE Project

Q: You’ve been in recovery for 10 years. When did your addiction start?

A: Addiction really sneaks up on you, and you’re not sure what’s happening at the time. At the age of 11, it started with alcohol and marijuana use. Between the ages of 11 up to 21, it progressed pretty rapidly, to the point where I was using prescription drugs. At that time, prescription drugs were online, and I was doctor shopping and hopping around to find them any way I possibly could.

I didn’t think I had a problem. Other people saw it. I hit a brick wall, and that was actually a jail cell. At that time, I wasn’t really quite sure what the issue was. I was always blaming other people and other factors in my life. It wasn’t until I was in that jail cell and had to detox. It was an extremely difficult detox. I was a mother of four, and I couldn’t fathom how I’d gotten to that point. During detox, I realized maybe I did have a problem.

Q: Tell me about your recovery journey.

A: Being in the jail cell, one of the things I learned was to ask for help. I wasn’t really quite ready to ask for treatment, but it was my get-out-of-jail-free card. I was transferred to a treatment center, and that was really the first time I had been introduced to the disease of addiction rather than the moral failing of addiction. I was surrounded by other individuals who were just like me. I felt like I was home for a change. I let other people take me under their wing.

Next month I’m defending my dissertation. I went from one extreme to the other. I knew I had to do something for the system.”

—Brandee Izquierdo

Once I got out of treatment and cleaned up the wreckage of my past, I knew I wanted to help other people. From there, I was told about this thing called peer support. I had felonies so I thought my life was over and I would never get a job. I didn’t want other people to go through what I’d gone through. I continued to refine my craft in recovery support services, but I also knew there were gaps in the system, and I got hooked on policy. It’s important to recognize the issue but also to implement solutions.

I went back to school, and next month I’m defending my dissertation. I went from one extreme to the other. I knew I had to do something for the system. When I left the jail cell and was hearing the ladies’ stories, I said, “I’m coming back for you. I don’t know how or when, but I’m coming back for you.” I’m trying to change infrastructures in behavioral health and criminal justice.

Q: What type of work is SAFE Project doing?

A: We work to create programs that are initiative-conducive so we can meet stakeholders where they are and move them toward their end goal. We have SAFE Workplaces [for employers and employees] that don’t believe they have a problem. We wouldn’t just walk away from that. We would create a softer approach for them and get them started. It might be with our No Shame pledge. It’s very simple, but at least it opens the door and starts conversation. Then we can move them into our other programs. If you’re a construction organization, do you have naloxone in your safety kits?

We customize programs. How I talk to SAFE Communities is going to be different than how I would talk to a SAFE Campuses administrator or a SAFE Veteran. With our SAFE Campuses initiative, we reach out to campuses and provide resources and educational assistance. We help them develop programs for collegiate recovery on campus. It depends on the community or the individual and what they need.

Q: How would you define SAFE Project’s mission?

A: Our overarching mission is to save a life every day. The reality is that how we save a life every day is going to be different. That was the reason SAFE Project was created. We can do things that perhaps other organizations can’t do because they’re bound to their missions. I say the broader the base, the higher the point of freedom. We have more opportunity to help people.

I definitely think we’re accomplishing [the mission] either directly or indirectly. It’s six degrees of separation in this recovery world. If I can impact one person, I can impact six more. Sometimes it’s exhausting because I live and breathe this every day. Some days it’s rainbows and sunshine; other days it’s a roller coaster, and I put my hands up and enjoy the ride.

Q: Why is it so important to dispose of unused prescription medications?

A: There’s a level of temptation. There’s the time where you may feel an ailment and you have a prescription in your medicine cabinet. My mother is living with me and had surgery, so opioids are in the house. Sixty-two percent of teenagers start using drugs because they’re easy to get in their medicine cabinets. The mental well-being of adolescents and youth is at a low point now. It’s about having conversations. Not everyone is willing or ready to have conversations with their kids, so having tools in the house to have those conversations is very important.

Q: How is SAFE Project participating in National Prescription Drug Take Back Day?

A: We know addiction doesn’t start on National Prescription Drug Take Back Day. It’s all year long. The CDC just released data, and we’re up to 93,000 overdose deaths [in 2020]. We’re also seeing an uptick in prescription drug prescribing. People are trying to figure out what to do in terms of substance use and mental illness.

Seventy percent of opioids that were prescribed for post-surgical use are left unused. We work with companies to provide disposal bags for prescriptions. We know everyone is stuck at home and that substance use is running rampant right now. We built a strong health partnership with [the company] Deterra and work [together] on a consistent basis. There’s a web address people can go to and request an individual pouch or bulk orders.

I was at a conference a couple weeks back, and none of the workplaces thought they have a problem. I know differently because I was that problem. Sometimes it’s an easier blow if you say, “You can continue to prevent that problem in the future by providing Deterra bags.” We keep having those conversations with everyone we engage with.

My endgame is having the ability to have a conversation with TreatmentMagazine.com just like I would with the barista in my coffee shop. Let’s normalize this to the point where people don’t feel shameful for having an addiction.”

—Brandee Izquierdo

We do larger media campaigns [around prescription drug disposal] during the months of October and April. I’m going to be honest—people are lazy. We’ve become accustomed to not doing things outside of our houses. At the beginning of recycling, everyone had to take it to an outside location. Now I have a recycle bin in our garage. We do a media campaign because it’s going to take some time to get everyone to a point where this is normalized.

Q: What is your ultimate goal in addiction prevention?

A: I come from a background in the behavioral health arena where there’s a lot of competition. It’s not intentional competition, but we waste a lot of time duplicating services. My goal is for us to unify and use resources in a cost-effective way to reach a broader population.

My endgame is having the ability to have a conversation with TreatmentMagazine.com just like I would with the barista in my coffee shop. Let’s normalize this to the point where people don’t feel shameful for having an addiction. If that conversation would have been happening around me earlier, it would have been such a different pathway for me.

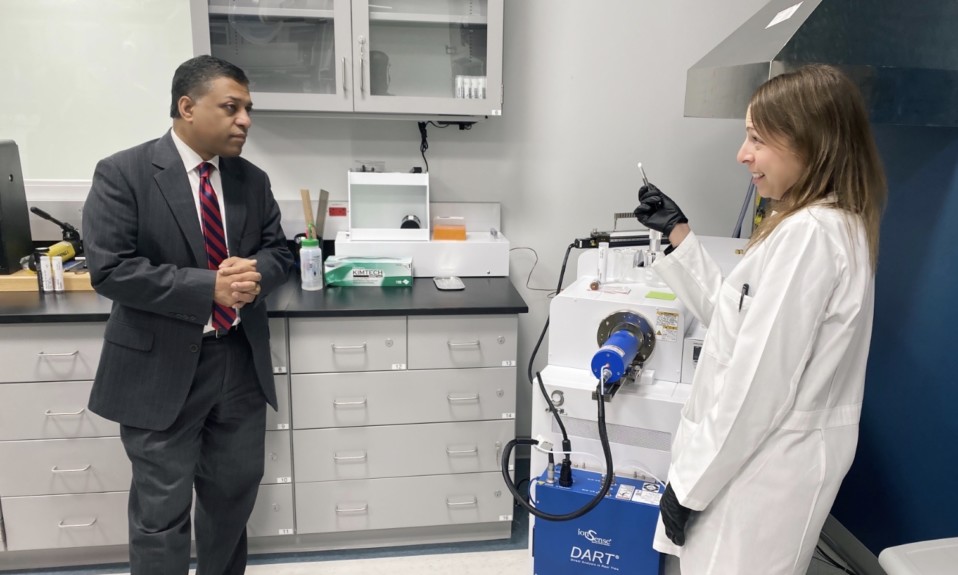

Top photo: Altin Ferreira