Alcoholism academic pioneer E.M. Jellinek’s 1960 study offers four reasons why

By Ryan Blackstock, Psy.D.

August 9, 2020Wherever you are in your experience helping someone you care about struggle with substance abuse, you may be wondering: Why is addiction called a disease? It didn’t use to be so, you may rightly remember.

Every so often this question gets attention in the media, and usually they bring in some celebrity who makes some statement that gets my blood boiling. There is so much moral stigmatization that occurs that people don’t bother to make distinctions between cause of problem and outcomes.

Let’s shed some light on this. When I teach courses in addiction studies at my psychology master’s program, I always ask students: When do you think we figured out alcoholism was a disease? Most guess somewhere in the 1980s or ’90s. This makes sense, as it’s when treatment for alcoholism began to get media attention.

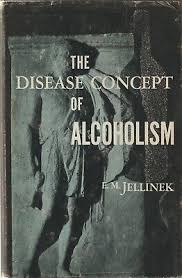

But it actually starts 20 years earlier. Alcoholism scholar and pioneer E.M. Jellinek, a professor at Stanford and Yale, among many honorifics, published a seminal book called The Disease Concept of Addiction in 1960. In it, he laid out his theory that addiction should be conceptualized as a disease, as it follows a parallel path to what one sees with disease. In his book, Jellinek also writes that there are socioeconomic factors at play, and openly published letters of criticism directed to him from other researchers. Jellinek wasn’t the first person to consider alcoholism a disease, but his work still continues to impact the treatment and recovery communities today.

The key term for Jellinek was “concept.” Jellinek intended for addiction to be referred to as a disease concept, and in my early training in the late ‘80s, it was called that. But over time, professionals dropped “concept” and just used the term disease exclusively. Saying “it’s a disease” is a much more definitive statement as opposed to “well, you have to think about it like a disease.” Addiction being viewed as a disease has opened the doors for ongoing research into its treatment. If addiction was simply a moral shortcoming, there would have been no need for scientific exploration.

Let’s look at the four points Jellinek makes about the addiction/disease connection. He cited four ways in which addiction is like a disease: 1. primary 2. progressive 3. chronic, and 4. fatal.

Let’s take each one by one and define what addiction and disease have in common:

PRIMARY: The simplest way to think about this aspect is that with few exceptions, addiction itself is the problem that must be treated in order for real progress to be made. The only exceptions are if the person is suicidal or a danger to themselves or others; psychotic and having active hallucinations or delusions; or has an eating disorder that needs medical intervention. Those factors all take precedent, as you can’t treat people if they are not alive or not functioning safely within reality. That said, besides these very extreme circumstances, addiction should be the main focus of treatment, Jellinek wrote, as it is the primary culprit of dysfunction and psychological pain.

PROGRESSIVE: We know that addiction tends to gets worse over time, and 60 years ago Jellinek was able to track this. He charted his famous “curve” or chart that shows addiction progression from early to late stages over time. The longer you have active addiction, the worse it gets. People in recovery will tell their narrative that reinforces this over and over.

CHRONIC: Jellinek’s believed that addiction and alcoholism were like a disease in that once you contracted it, you were never without it, though you could be non-symptomatic. The American Psychiatric Association’s definitive Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM 5 (2013) diagnostic guide codes the addictions that are non-symptomatic/in recovery as “in remission”—following long-standing diagnostic tradition. While this suggests that there is no cure for addiction, it should not be thought of this way: Much like cancer, the goal and the hope is to healthily stay “in remission.”

FATAL: Jellinek sadly pointed out when he wrote his book in 1960 that most alcoholics and addicts die before getting treatment. We can take hope here: things have improved greatly since. That said, addiction is still a systemic problem regularly affecting a small portion of the population, and there is still a lot of stigma around addiction—but that we can fight. Those of us who work in the treatment community are laboring mightily to help eradicate this stigma and increase instances of successful recovery with the goal of addiction remission.

Treatment continues to evolve, of course, and modern concepts take a different approach than Jellinek. We now focus on models of exposure (studying how the brain changes over time due to drug use, resulting in addiction) as well as susceptibility (looking at genetic risk of becoming addicted, often backed up by family history).

Our field also continues to research addiction from a neurocognitive perspective with the hope of finding medical interventions that help treat addiction. The availability and use of a drug like Narcan to help prevent opioid overdose is one example.

Bottom line: Addiction is not a moral problem. It is still best understood to be like a disease that inevitably results in (often an abundance of) moral consequences—these we can all work to change and permanently put into “remission.”

Ryan Blackstock, Psy.D., received his doctorate of psychology from the Center for Humanistic Studies in 2006 and has worked as an addiction counselor since the early 1990s. He earned a distinguished service award from the National Kidney Foundation (Michigan chapter) for pioneering a substance abuse education program for people awaiting organ transplant. Dr. Blackstock teaches at the Michigan School of Psychology master’s program. In his free time, he enjoys game design, playing heavy metal and studying symbolic aspects of ancient Egypt.