A VR program developed at Indiana University promises to provide people in recovery from addiction the chance to meet their future, sober selves

By Mark Mravic

For people with substance use disorder (SUD), the struggle is often day to day. In both addiction and recovery, time horizons are shortened and the future lacks focus, making it difficult to plan for—or even imagine—what life might be like six months, a year or five years down the road.

Studies have shown that for people with SUD, time scales are drastically compressed. “When you take the future out of the decision-making apparatus,” says Brandon Oberlin, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry at Indiana University, “things like 30-year mortgages and career advancement and even cultivating meaningful long-term relationships go out the window—because those require investment in the present for an expected future outcome.” Oberlin believes that for people in recovery from SUD, virtual reality—which presents realistic, immersive visions of imagined worlds—can have a hand in changing that dynamic.

Intrigued by an economics study in which college undergraduates changed their saving behavior after interacting with their future selves through VR, Oberlin thought about how such technology might be harnessed for substance use treatment—particularly in the early stages of recovery, when relapse rates are high. Working with Indiana University’s Informatics, Computing and Engineering department and with Andrew Nelson, an Indianapolis-based VR designer, Oberlin and his team created an immersive virtual reality experience in which people in recovery from SUD encounter “avatars” of their future selves—lifelike, fully animated images that converse with participants in their own voice and discuss potential alternative futures.

The idea is to bolster the subject’s connection with the future, stretching out their decision-making timeline to envision rewards down the road. “If we can make the future more vivid, more real, more salient, we help it compete with the present,” says Oberlin, who has been studying issues in substance use, particularly around decision-making and temporal choice, for the past two decades. “Because of the power of immersive virtual reality, we can make the future seem real and personally relevant.”

Two Virtual Reality Futures

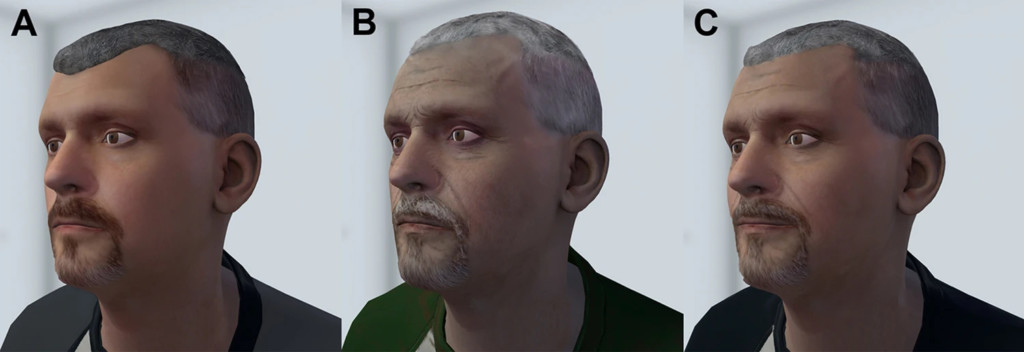

Oberlin’s pilot study recruited 21 people in early recovery, with a median age of 34. Designers created three avatars for each participant: the Present Self, the SUD Future Self and the Recovery Future Self—the latter two both age-progressed 15 years. The SUD avatar was made to display visible signs of sustained drug use, while the recovery avatar appeared healthy—“gracefully aged and looking accomplished,” as Oberlin puts it.

The research team individualized each participant’s narrative with information drawn from clinical interviews—what mattered to them, names of loved ones and how substance use had affected them, as well as their perspectives on the future—what they’re looking forward to, and what they might fear. They were also asked how their substance use had affected them—some had lost their driver’s license or custody of their kids, or spent time in jail—and what they would like to change—rebuilding their relationship with their spouse, for instance, or going back to school.

The VR experience was conducted through an Oculus headset and lasted five to seven minutes. In the paradigm, set partly in a public park, the participant encounters his or her present self, who foreshadows multiple possible futures and then says, “Choose your future.” The participant is taken into the SUD timeline, where the future self describes the past 15 years and the costs of substance use, while displaying telltale signs of continued drug use. Then the participant is given the chance to choose another future. In the recovery timeline, the healthy future self recounts the past 15 years’ successes, the result of continued recovery.

To conclude the experience, participants are debriefed by their present self, who promotes agency and emphasizes the possibility of a positive future. “The future is real,” the avatar says. “The future will happen. Things you do now affect future outcomes. You can do this.”

Afterwards, participants filled out questionnaires about the experience, detailing their connectedness with the future and their confidence in recovery. Over the ensuing 30 days they received daily text-message images of their recovery future selves, reinforcing the positive timeline.

“It was a really powerful experience. I don’t want to be that guy in 15 years. … If I stay on the path, I can see the life I envisioned for myself.”

—VR study participant

The results were promising. Of the 21 participants, 18 (85%) remained abstinent after 30 days, and most said their cravings were reduced. They also improved regarding “delay discounting,” the tendency to prefer smaller rewards immediately versus larger rewards later. In interviews, participants said they were emotionally engaged with the experience, and both of futures depicted—the negative as well as the positive—seemed to motivate them.

Some interview responses:

- “It made me imagine what it would be like the next 15 years to get to that point, all the wasted money, opportunities, and relationships—it made me feel sad. Hearing myself saying getting sober was the best decision I ever made stuck with me.”

- “It was a really powerful experience. … I don’t want to be that guy in 15 years. Having a virtual representation of the future is helpful because in recovery we live in the present, so we don’t know what the future holds. … If I stay on the path, I can see the life I envisioned for myself.”

- “I was shocked. … In the active addiction future, seeing myself twitch and move around a lot … that could be me in 15 years if I don’t do what I need to do.”

- “Having myself speak to myself about the choices I have made, and seeing the bad future and good future, was life-changing.”

One participant spoke specifically about being able see a vision the future, rather than just talk about it (recalling the “show, don’t tell” technique in storytelling): “Putting different futures together, you don’t really visually [see that]. How many people tell you over and over this and this and this can happen? Even though it wasn’t hyper realistic, it was still something to think about.”

While the results were encouraging, Oberlin notes, “This isn’t a cure. I don’t want to overstate it. I’d like to believe that it could help, and if it can help even a little bit, I think it’s a technology and an approach worth exploring.”

The Future of VR and Recovery

Oberlin’s team plans to continue its work, which will include larger clinical trials, supported by more than $4.9 million in recent funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). One planned study will deliver VR experiences remotely via wireless headsets that participants can use at home. Oberlin has also co-founded a startup, Relate XR, to develop the technology and explore its commercial potential.

“This experience enables people in recovery to have a personalized virtual experience, in alternate futures resulting from the choices they made,” Oberlin says. “We believe this could be a revolutionary intervention for early substance use disorders recovery, with perhaps even further-reaching mental health applications. The ultimate goal of our work is to leverage state-of-the-art VR technology for providing therapeutic experiences to support early recovery—a very dangerous time period marked by a high risk for relapse.”

Top photo: Eric Hanus, Indiana University