Stigma is a core problem with addiction. The words we use are at the core of the solution

By Darya Daneshmand

At the start of my freshman year in college, one of our welcoming speakers addressed issues of diversity. During his lecture, he listed a series of identities and asked members of the audience to stand up when he named one of ours. “I am a first-generation college student.” “I am a student-athlete.” “I am of Middle Eastern descent.”

What I remember most clearly was the identity no one stood up for: “I am an addict.”

Walking away with a friend afterward, I said there was likely someone in that audience to whom it applied.

“Really?” she responded, adding, “Even if you’re right, I doubt anyone would stand up.”

That raises the question, Why would it be so difficult to stand up?

Societal views toward addiction are rife with stigma, negative stereotypes and misinformation. It is unsurprising that many do not want to expose a piece of themselves that may not be well-received or understood by much of the population.

A few years later, when I began working with TreatmentMagazine.com, I learned more about the weight of words, their pejorative force and the importance of understanding that only the community in question retains the right to use terms such as “junkie” and “addict.” So someone may indeed courageously stand up and say “I am an addict.” But others—those in the audience—should say, “She has a substance use disorder.”

The Research on Stigma’s Impact

Years of investigation have shown that stigma around addiction substantially influences health outcomes and creates a treatment barrier for those seeking help. And we well know that a mere 10% of people with substance use disorders receive treatment.

The words we use help create this barrier; the evidence is overwhelming.

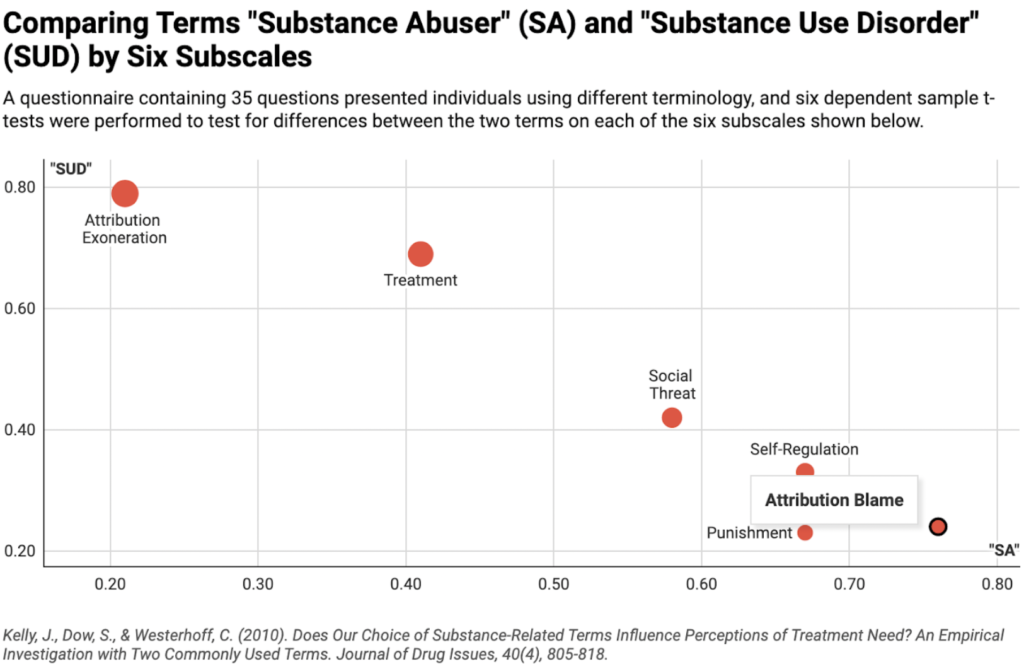

In one study, individuals were presented with vignettes describing those struggling with addiction using different terminology—either “substance abuser” (SA) or “person with substance use disorder” (SUD). These participants were then asked questions aimed at their perceptions of the individuals described. Questions and their corresponding responses were categorized into six areas for analysis of how different views may be influenced by word choice. The categories:

- Treatment – Recommend treatment to decrease substance use; need for psychiatrist referral, etc.

- Punishment – Recommend punishment to decrease substance use; benefit from disciplinary procedures, etc.

- Social threat – Act violently; willing to have as a neighbor or close friend, etc.

- Causal attribution: Blame – Substance use problem caused by a reckless lifestyle; responsible for consequences of use, etc.

- Causal attribution: Exoneration – problem is more likely inherited; problem is genetic in origin, etc.

- Self-regulation – Able to stop using alcohol/drugs if they wanted; overcome problem without professional help, etc.

The most striking discovery was the contrast between responses to questions categorized under “exoneration” and “blame.” The data show that individuals were far more likely to attribute a person’s addiction to external factors when the term “SUD” was used, while they were more likely to blame that same person for their addiction when the term “substance abuser” was used. Those described as having a substance use disorder were also perceived as having a greater need for treatment, while “substance abusers” were more likely to be expected to overcome their addiction on their own.

Such findings are corroborated by an analysis of implicit biases elicited by different addiction terminology. In a 2018 study on substance use, recovery and linguistics, participants performed an association test, with results finding that the strongest associations were those between terms such as “opioid abuser,” “alcoholic” and “addict”—negative words, according to the hypothesis—and bad. In comparison, hypothesized positive terms such as “opioid use disorder” and “alcohol use disorder” were associated either more with good or significantly less with bad, even if they retained their negative association. Essentially, participants’ immediate perception improved across all four areas of comparison when using terms aligned with the disease model of addiction.

Research continues to explore the neurological, genetic and environmental roots of addiction, but the language we use has the power to either reinforce or undermine the relationship between these facts and public perceptions.

Guidelines to Destigmatize Language

In recent years, a positive shift has occurred in the way substance use is viewed both within medical communities and among the public. The American Psychological Association (APA) first listed the categories “substance abuse” and “substance dependence” in the 1980 edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-3). In DSM-5 in 2013, it revised its approach to substances and addiction, removing the words “abuse” and “dependence” and creating the single category, “substance use disorders.” In the next few years, organizations such as the National Center on Disability and Journalism (NCDJ) and the Associated Press (AP) changed their guides for writing about addiction to align more closely with the disease model, which places the individual before the struggle and eliminates the connotation of personal culpability.

Among the recommendations in the NCDJ’s 2021 guide:

- Addiction differs from dependence, so refrain from using the words interchangeably

- Use the word “misuse” in place of “abuse” when describing harmful drug usage

- The terms “clean” and “dirty” with regard to drug test results are considered derogatory because they equate symptoms of illness to filth. When referring to a drug test, state that the person “tested positive for (drug).”

The AP, whose style guide is the leading reference for media and corporate communications in the U.S., provides similar guidelines for word usage. The NCDJ notes:

- The Associated Press suggests avoiding words like “abuse” or “problem” in favor of the word “use” with an appropriate modifier such as “risky,” “unhealthy,” “excessive” or “heavy.” “Misuse” also is acceptable

- Don’t assume all people who engage in misuse have an addiction

- Avoid “alcoholic,” “addict,” “user” and “abuser” unless individuals prefer those terms for themselves or if they occur in quotations or are names of organizations, such as Alcoholics Anonymous

The emergence of such guides points to a positive trend, but the lack of consistent implementation in public communication and discourse shows that progress is slow. I asked TreatmentMagazine.com Editor in Chief William Wagner about his perspective on the most pressing barriers in the field of addiction treatment. “In two words,” he said, “data, stigma.” A number of entities—nonprofits, businesses and advocates alike—are joining to uplift communities by tackling the two in one stroke.

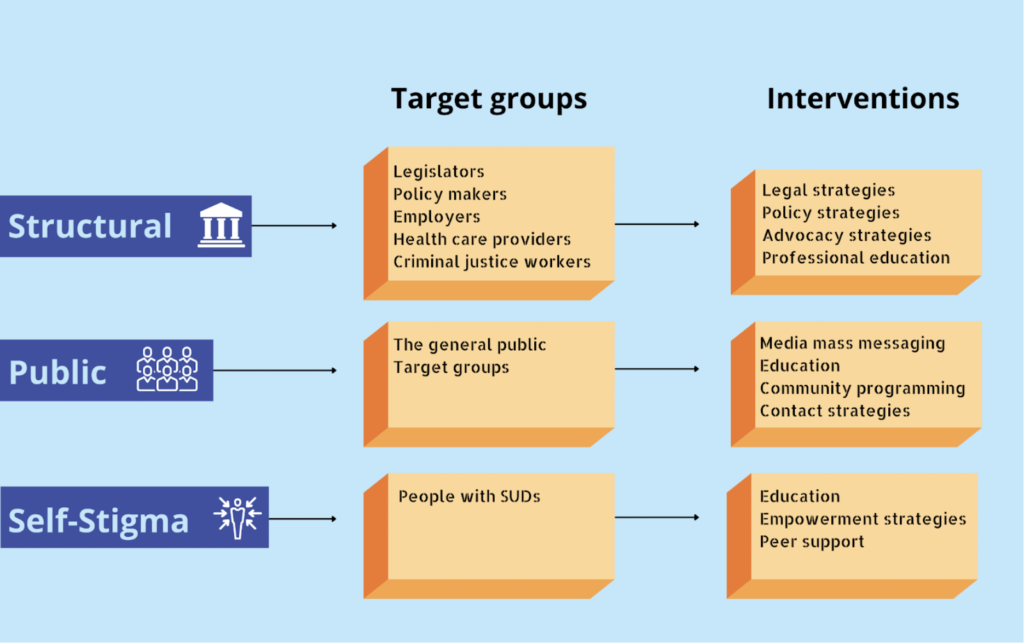

In collaboration with The Hartford, Shatterproof developed the Shatterproof Addiction Stigma Index (SASI) to assess attitudes about substance use and perceptions of those with SUD. Internalized feelings of exclusion and shame, or self-stigma, are prevalent side effects of widespread structural and public stigma. Other groups, including TreatmentMagazine.com, publish personal stories of hope, confronting stigma through exposure. Methods of fighting stigma are numerous and address its different forms.

What You Can Do to Fight Stigma

Start dialogue about addiction and recovery, and the stigma surrounding it. Exposure has been proven to lessen stigma by humanizing the experience of addiction.

Pay attention to the words you choose, and learn about the ways they may influence others’ beliefs.

Learn, and educate others. Ignorance allows stigma to thrive, so this is a great way to lessen prejudice.

Speak up where you see stigma being perpetuated. Upon hearing inaccurate portrayals of addiction or those with SUDs, use language that questions misinformed perceptions without anger or eliciting guilt, and people are likely to listen and hear you.

Together, we can create a space where it isn’t as difficult to stand up and lay claim to our personal battles, where we can expect the eyes that fall on us when we do to view us without judgment, and where a desire to understand is cultivated as the response to discovering the struggles of our neighbors and peers.

Artwork by Sara Akhtar @saraakhtar.art