It’s a sordid tale that, on a certain level, shows how deeply the opioid epidemic has burrowed into our society

By Mark Mravic

It’s got a mother-son murder, a fatal drunken boat crash, a botched suicide-for-hire scheme, insurance fraud, embezzlement, abuse of power, mysterious cold cases from years back, shady judicial rulings, curious coroner findings and as many twists, turns, side channels and fetid pools as the languid waters that meander through South Carolina’s Lowcountry, the backdrop for it all. It’s the Murdaugh Murders saga, a sordid Southern noir that has captivated the nation over the course of this summer. And since this is America in the 21st century, it’s inevitable that the story has an opioid angle.

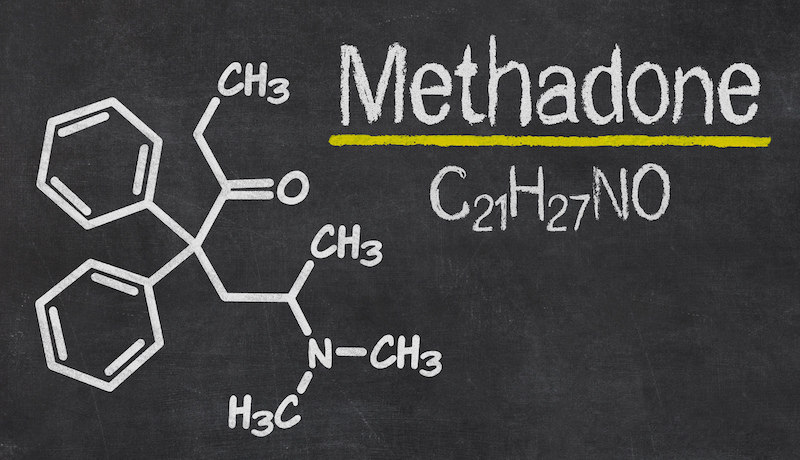

Where to begin? On Sept. 4, Alex Murdaugh [pictured above], a lawyer with the South Carolina firm of Peters, Murdaugh, Parker, Eltzroth & Detrick—founded in 1910 by Murdaugh’s great-grandfather—called 911 to report he’d been shot in the head by an unknown assailant as he was stopped to fix a flat tire along a rural road in Hampton County, S.C. Murdaugh, 53, was airlifted to a trauma center in Savannah, Ga., for treatment of his injuries, which proved not to be life-threatening. But his story began to unravel almost immediately, and days later Murdaugh admitted that he had staged the shooting, hiring a former client to kill him so that Murdaugh’s elder son, Buster, could receive a $10 million insurance payout. Murdaugh released a statement saying he was resigning from the law firm and had checked himself into a rehab center to deal with what he called a “long battle” with opioids.

If, for some reason, the oxy story—like so many in this twisted narrative—turns out to be less than true, it would amount to a cynical exploitation of the actual trauma and distress opioids have caused so many Americans. If Alex Murdaugh does have an addiction, it reveals the depths into which even the most powerful figures in a community can be plunged by opioids.”

“I am immensely sorry to everyone I’ve hurt, including my family, friends, and colleagues,” the statement read. “I ask for prayers as I rehabilitate myself and my relationships.”

But if you’ve been following the increasingly feverish headlines, crazy morning show interviews and gripping true crime podcasts, you’ll know that’s far from the whole story. Indeed, three months earlier, on June 7, Alex Murdaugh had made another 911 call—this one to report that he’d found his wife, Maggie, and younger son, Paul, shot to death on the family’s 1,900-acre hunting estate in Islandton, S.C. Those killings, still unsolved, opened up a pandora’s box of questions and speculation.

A String of Tragedies

Backtrack to 2019. On the night of Feb. 23 that year, Paul Murdaugh and a group of five friends, all underage, loaded up Alex Murdaugh’s 17-foot Sea Hunt fishing boat with illegally purchased booze and headed out to an oyster roast. After partying there for several hours, the group returned to the boat and continued the revelry as they cruised the rivers and streams. But as the hours wore on, some became anxious to get home, as they observed Paul transforming into a violent and angry alter-ego called “Timmy” that emerged when he drank too much. As Paul’s behavior and driving became more erratic, passengers pleaded for him to slow down and take them home. To no avail. Shortly after 2 a.m., the boat smashed into a bridge abutment on a creek near Parris Island. Three people were thrown into the water. One, Mallory Beach, never resurfaced. Her body was found a week later, miles downstream.

Police seemed to drag their feet on the investigation. No breathalyzer test was administered to Paul Murdaugh or the others, and despite the insistence of several passengers, investigators initially said they couldn’t determine who’d been at the wheel at the time of the crash. Witnesses also say Alex Murdaugh turned up at the hospital where the passengers were taken, attempting to influence their recollection of events. Eventually, however, his son was charged with three counts of felony boating under the influence. Paul Murdaugh was out on bond awaiting trial when he was murdered, along with his mother, in June.

While investigators have yet to identify a suspect in the killings, Alex Murdaugh was named a “person of interest.” In addition, the probe turned up evidence that has led investigators to re-open a previous case. In 2018, the Murdaugh’s longtime housekeeper, Gloria Satterfield, died from what was deemed an accidental “trip and fall” in the Murdaugh house. Recent reports suggest Alex Murdaugh saw the death as an opportunity to bilk his own insurance company. He connected Satterfield’s sons with friendly lawyers and bankers to carry out a wrongful death claim against Murdaugh. The suit was apparently settled for $505,000; but while the lawyers allegedly received some $166,000 in fees from the insurance company, the sons said in a lawsuit filed this month that they had yet to receive anything. Now their lawyers say they have reason to believe there might have been as much as $4.3 million paid out on the claim, of which their clients haven’t seen a dime.

The June murders also cast new light on yet another unsolved fatality. In 2015, the body of Stephen Smith, 19, was found on a rural road in Hampton County. He’d suffered blunt force trauma to the head, which a coroner eventually attributed to his having been struck by the sideview mirror of a truck while he was walking along the road—though no evidence of a vehicle impact was ever found. Smith’s mother, Sandy, didn’t buy the account, telling reporters after his death that she believed he had been killed by several local youths from “prestigious families” because he was gay, and that Stephen may have had a “fling” with one of those youths. Investigators at the time received anonymous tips that linked Stephen Smith and Buster Murdaugh, who had been high school classmates. Still, the case went cold—until June 22 of this year, when the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division announced it was opening a new investigation into that death, based on evidence that turned up in the June double-murder probe.

The Murdaugh Opioid Connection

The Murdaugh family has ruled the Lowcountry of South Carolina for nearly a century. The same great-grandfather, Randolph, who founded the law firm also served as Solicitor of the 14th Circuit, the chief prosecutor for the five counties in the southeast corner of the state. That job passed down to his son, and then to Randolph Murdaugh III, Alex Murdaugh’s father. Randolph’s departure for private practice in 2005 marked the first time in nearly nine decades that a Murdaugh didn’t run the prosecutor’s office in the area, giving the family immense power over the justice system. And their tentacles still run deep. In June, Connor Cook, who was injured in the 2019 boat crash, filed a petition alleging that state and county investigators attempted to divert the focus of the probe away from Paul Murdaugh and make Connor the fall guy. Moreover, speculation is now rampant that the reason the Smith and Satterfield deaths went cold is down to the influence of the Murdaughs, and the fear of crossing them.

Now, however, Alex Murdaugh is reportedly being investigated by a grand jury for potential obstruction of justice related to his activities after the boat accident. New investigations also offer the promise of truth emerging in the other deaths. And Alex’s departure from his law firm? It turns out he had actually been forced to resign after his partners discovered he’d “misappropriated funds” from the firm—with the figures reported to be in the millions of dollars. “The Murdaughs were once seen as the law,” one South Carolina resident told The Daily Beast. “Now they’re finally seeing the other side of it.” It’s telling, though, that the person and others quoted by the Daily Beast wished to remain anonymous “for fear of professional retribution.”

Harpootlian said Murdaugh had used oxy to get through the murders of his wife and son, as well as his father’s cancer death shortly thereafter, and he was in a ‘massive depression’ when he concocted and went through with the suicide scheme.”

As for opioids, in September, Murdaugh’s lawyer, Dick Harpootlian, told the Today show’s Craig Melvin that when he and a colleague spoke with Murdaugh in rehab, it was “the first conversation we ever had with him where he wasn’t on opioids or oxy.” Harpootlian said Murdaugh had used oxy to get through the murders of his wife and son, as well as his father’s cancer death shortly thereafter, and he was in a “massive depression” when he concocted and went through with the suicide scheme. Harpootlian also said that Murdaugh spent the “vast majority” of the money he embezzled from the law firm on drugs—to which Melvin, a South Carolina native, responded skeptically, “Dick, that’s a lot of oxy.”

Melvin may have been right to raise an eyebrow. Given that Alex Murdaugh already lied about his roadside shooting and is the subject of multiple investigations involving fraud, obstruction, abuse of power and more, there’s plenty of reason to question other claims he’s made.

If, for some reason, the oxy story—like so many in this twisted narrative—turns out to be less than true, it would amount to a cynical exploitation of the actual trauma and distress opioids have caused so many Americans. If Alex Murdaugh does have an addiction, it reveals the depths into which even the most powerful figures in a community can be plunged by opioids. Whichever the case, the Murdaugh Murders saga is yet more evidence of how the opioid epidemic has insinuated itself into every stratum of society, and practically every story we hear—even the wildest ones.

Top photo: AP Images; bottom photo Conrad Ziebland