The Colorado-based organization has provided scores of Indigenous people with a new lease on life

By Jason Langendorf

Twenty-two years ago, when Kateri Coyhis was 16, she had already been addicted to meth and alcohol for about a year. A young Native American woman from the Mohican Nation, who hadn’t spent time around her culture up to that point, was suddenly invited on a journey that she was skeptical of from the start.

Coyhis was intimately familiar with White Bison, the Colorado Springs, Colo.-based organization that had founded the Wellbriety Movement, which strives to inspire people “to go on beyond sobriety and recovery, committing to a life of wellness and healing every day” and which provides training and resources for culturally sensitive addiction treatment to individuals and facilities across the country.

Now White Bison’s founder and president himself was urging Kateri to join his group on what was being called the “Journey of the Sacred Hoop: The Wiping of the Tears”—an expedition that would lead its participants from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., over three months and 3,000 miles … on foot.

“What do you think about that?” asked Don Coyhis, White Bison’s leader and, as fate would have it, Kateri’s father.

“Well, I think you’re crazy,” Kateri told Don. At the time, she meant it.

“Pack your bags,” Don told his daughter. “We leave in two days.”

Origins of White Bison

Don Coyhis had grappled with his alcohol use before (and even after) founding White Bison and the Wellbriety Movement in 1988, when Kateri was only 7 years old. When he decided to give himself over to sobriety, it was with the intention of saving himself and other struggling Native Americans, who have been disproportionately affected by addiction and underserved by the treatment community.

“I just said to the creator when I got sober, ‘You take my life of running, and I’ll do whatever you say from now on,’” Coyhis recalled in Journey of the Sacred Hoop, a documentary detailing White Bison’s L.A.-to-D.C. passage. “‘Every day, I’ll get up and say, ‘What do you want today? And that’s what I’ll try to do.’ So I fell asleep, and when I woke up, that’s when I knew I was to take this hoop across the United States.”

That hoop, inspired by a vision, is at the core of White Bison and the Wellbriety Movement. In a prophecy from one Native American tribe, it was said that someday a white buffalo calf would be born, turn four colors and then turn white again—a signal that a time of healing had come. So when Coyhis, searching for ways to fulfill his promise of service, was instructed by South Dakotan elders to create a hoop symbolizing many of the elements of the prophecy, he did.

In May 1995, in a mountain sweat lodge, Coyhis and his group built the Sacred Hoop—a sapling bent and coupled into a circle, measuring about an arm’s length in diameter. It contains 100 eagle feathers and four colored ribbons—red, yellow, black and white—that represent the Four Directions, as well as people from all races and cultures. Blessed by a multicultural gathering of elders who placed the gifts of healing, hope, unity and the power to forgive, the hoop has since traveled more than 75,000 miles to Indigenous communities across the country.

Although the Sacred Hoop is meant to inspire and give purpose and strength to all people, it holds special meaning to Native Americans. Coyhis and White Bison have traveled with the hoop to visit tribal colleges, reservations, community centers and anywhere with Native American populations interested in helping Indigenous people embrace their culture and begin to break a cycle of trauma, violence and addiction.

“This is a journey we must make ourselves,” Coyhis said. “We are bright, we are brilliant, we are smart, we are educated. We have our culture, elders, songs. We have all the tools necessary.”

Journey of the Sacred Hoop

The Sacred Hoop’s journey was launched to help raise awareness about domestic violence against women and children, specifically those among Native American populations. But the theme made sense to all involved. Almost from the beginning, White Bison recognized that many of the problems in Indigenous communities are intertwined: The organization’s original mission—to help Native American youths find sobriety from alcohol—quickly expanded when Coyhis realized the scope of the problem.

On April 2, 2000, when Kateri Coyhis took her first steps away from Los Angeles on the journey, her father didn’t know precisely what she was going through. But he sensed that something was off, and knew it was significant enough to pull Kateri out of school and have her make the long trip with people from her culture, many of whom had dealt with their own addiction issues.

Perhaps Don suspected that his daughter was dealing with her own substance issues. What he didn’t know was that she was making the trip while experiencing withdrawals.

“Nobody knew that, so I was detoxing in secret,” Kateri says. “But it was the very first time that I got to be around my culture. It was the very first time that I got to really be surrounded by people that were in recovery, too. And that’s kind of what started me on my path to recovery. White Bison and the Wellbriety Movement saved my life, and I’ve been hanging around the membership ever since.”

In fact, Kateri Coyhis is now White Bison’s executive director, a position she has held since 2020. “I definitely wish I could say I never used alcohol or drugs again,” Coyhis says. “But this past April, I celebrated 10 years of continuous wellbriety.”

Although White Bison doesn’t offer direct services, its programs—youth and adult treatment, family wellness, parenting and re-entry from incarceration, among others—are often infused with, or in some cases directly address, the need for healing from intergenerational grief and trauma in Native American communities.

And this fall, in Canada—Red Deer, Alberta, from Sept. 22-25—White Bison will conduct its first international Wellbriety Conference. Kateri says the organization has plans for another in the spring.

“We are also starting to expand programming into New Zealand and Australia and the U.K. and Ireland and Mexico, and all these other places that have indigenous populations as well,” Kateri says. “But even though we do take a culturally based approach, there are many, many different pathways to recovery. We’re one, and if that really happens to work for you, then great, you’re welcome to join the circle.”

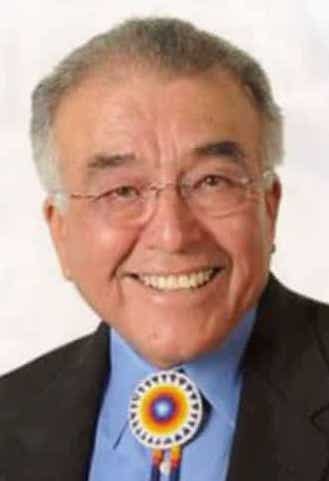

Top photo: Peter Foster