Get ready, treatment community: New research foretells lasting post-COVID addiction and mental health aftershocks and problems

By William Wagner

October 22, 2020

We’re still in the tight grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, yet the time is now to begin preparing for the addiction and mental health aftershocks. Much like with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), certain segments of the population will continue to be damaged by the pandemic even after it has receded into history.

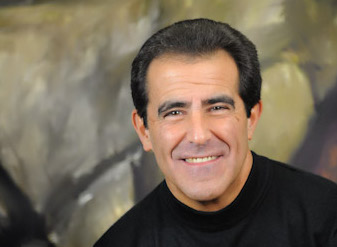

The message couldn’t be more blunt, and it comes courtesy of research from Michael Zvolensky, Ph.D., and his team at the University of Houston. Their findings recently were published in Psychiatry Research and Behaviour Research and Therapy.

All the models of psychological vulnerability predict that we’re going to see long-term effects from a psychological perspective as a result of the pandemic, which would include behavioral health and addiction, regardless of whether a vaccine or drug treatment comes around.”— Michael Zvolensky, Ph.D., director, University of Houston’s Anxiety and Health Research Laboratory/Substance Use Treatment Clinic

“All the models of psychological vulnerability predict that we’re going to see long-term effects from a psychological perspective as a result of the pandemic, which would include behavioral health and addiction, regardless of whether a vaccine or drug treatment comes around,” Zvolensky, director of the University of Houston’s Anxiety and Health Research Laboratory/Substance Use Treatment Clinic, told TreatmentMagazine.com.

“COVID represents a large-scale unpredictable, uncontrollable kind of stressor. Individuals with certain types of psychological vulnerabilities, such as preexisting mental health problems, are going to be highly reactive to that. As a result, their mood problems will heighten. That will increase the probability that they’ll try to down-regulate the stress through many different means: isolation, substance use, etc.

“Therein lies a very sticky situation. Once those problems start to emerge, they’re very difficult to change.”

Zvolensky is conducting six separate studies involving 800 people. The results of the first three studies, with 180 participants who were surveyed about their COVID behaviors, were what wound up in Psychiatry Research and Behaviour Research and Therapy. So far, his work has created at least an outline of the potential fallout from the pandemic.

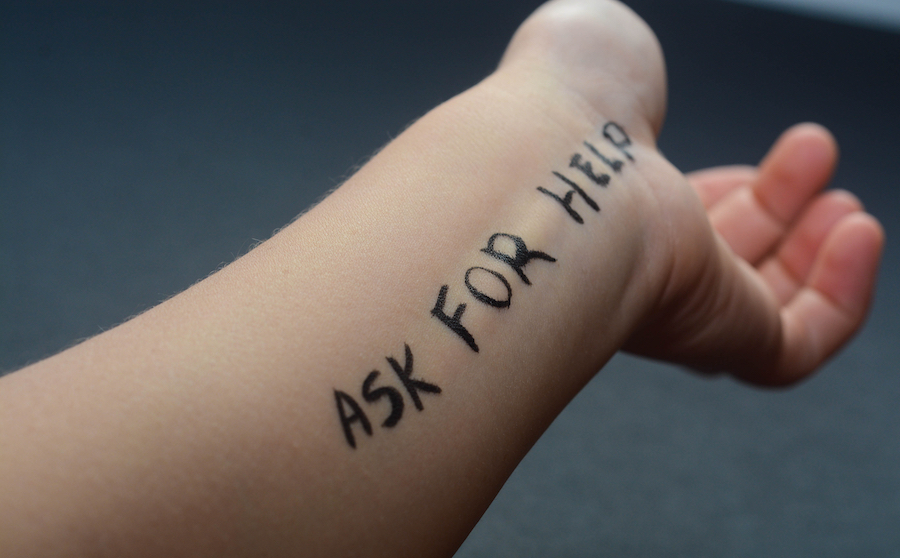

But if you start to notice you’re slipping—losing control of substance use in whatever capacity—you also need to be in a position to recognize it’s okay to reach out, whether that’s AA or a religious area or social support or evidenced-based care.”— Michael Zvolensky, Ph.D.

“For a certain subset of the population with vulnerabilities—or from what’s nerdily called a diathesis-stress perspective—psychological and biological stress is activated [by the pandemic],” Zvolensky says. “Some people might have already been struggling with mental health problems. For that certain subgroup, COVID probably brought out clinically significant distress.

“Many people [in the general population] will recover just fine, but a subset won’t. We don’t know the exact percentage, but a subset won’t without intervention or targeted care. It’s not that it can’t be treated, but we’ll have to roll out targeted public health efforts to address this need.”

In the meantime, Zvolensky has some common-sense suggestions for keeping it together.

“I have been encouraging people to be very mindful that this is a real thing. This is a real stressor,” he says. “Focus on self-care, doing things that facilitate clear thinking, cognitive control and emotional health. For example, make sure you get extra sleep and are eating nutrient-rich food. Engage in regular physical activity. All those things bring about a strong response over time. But if you start to notice you’re slipping—losing control of substance use in whatever capacity—you also need to be in a position to recognize it’s okay to reach out, whether that’s AA or a religious area or social support or evidenced-based care.”

COVID-19 has forced the public health community to refine emerging ways of reaching out, namely telehealth and addiction-oriented apps. The potential in these virtual areas was apparent even in the early days of the pandemic. Tessa Voss, MA, LADC, CADC II, executive director of the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, Calif., noted it in an interview with TreatmentMagazine.com last May.

“Addiction treatment won’t ever be the same,” Voss said. “The doors to virtual care have swung open, and it’s been remarkably successful. We have been able to reach people who otherwise may not have access to treatment.”

Tech, however, will be only part of the solution when the dust from COVID finally settles.

“[Virtual care] won’t be a panacea,” Zvolensky says. “It will be another layer of potential therapeutic resources that the public can access. As a population, we really need to learn from this experience. The chance of future pandemics is certainly there. We need to teach ourselves to be more adaptive in the future.”