Many U.S. counties have zero approved caregivers

By Jason Langendorf

August 15, 2020Forty percent of counties in the United States had no healthcare provider with a waiver permitting them to prescribe buprenorphine, the medication used in treating opioid use disorder (OUD), according to a report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General.

Based on Centers for Disease Control 2020 pre-COVID calculations, the number of drug overdose deaths since 1999 is expected to approach 1 million by the end of 2020—two out of three of which will likely involve an opioid. Although the rate of overall overdose deaths declined in 2017 to 2018 (a decrease of 4.1% from 2017 to 2018), death rates involving synthetic opioids (excluding methadone), rose by 10% during that same period.

While certain legislative efforts appear to be helping stem overall drug overdose rates in the U.S., the number of doctors approved to prescribe buprenorphine—and their geographic distribution—has created a treatment vacuum. Geographic disparities where waivered physicians can be found has effectively created a vacuum for a large population of rural patients in need of treatment medication. Worse, a looming shortage of total physicians could make it more difficult to address opioid-addicted patient needs in the coming years.

Currently, fewer than one in 10 of U.S. physicians are waivered to prescribe buprenorphine, and despite a recent loosening of certain regulations around prescription and administration of the medication due to the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act,, the number of caregivers who are waivered doesn’t come close to serving the patients allowed under the current laws.

“Fewer than one in 10 of U.S. physicians are waivered to prescribe buprenorphine, despite a recent loosening of certain regulations around prescription and administration of the medication.”

One strategy proposed to reach underserved patients has been waivering i emergency room doctors, but a 2019 Yale study published in May 2020 issue of JAMA Network Open weighing this approach identified significant pushback from caregivers—including a lack of formal training, limitations on time, and limited knowledge of local treatment resources.

Liability is likely another significant concern for ER physicians, who can be the target of litigation based on how, and whether, they address a specialized condition.

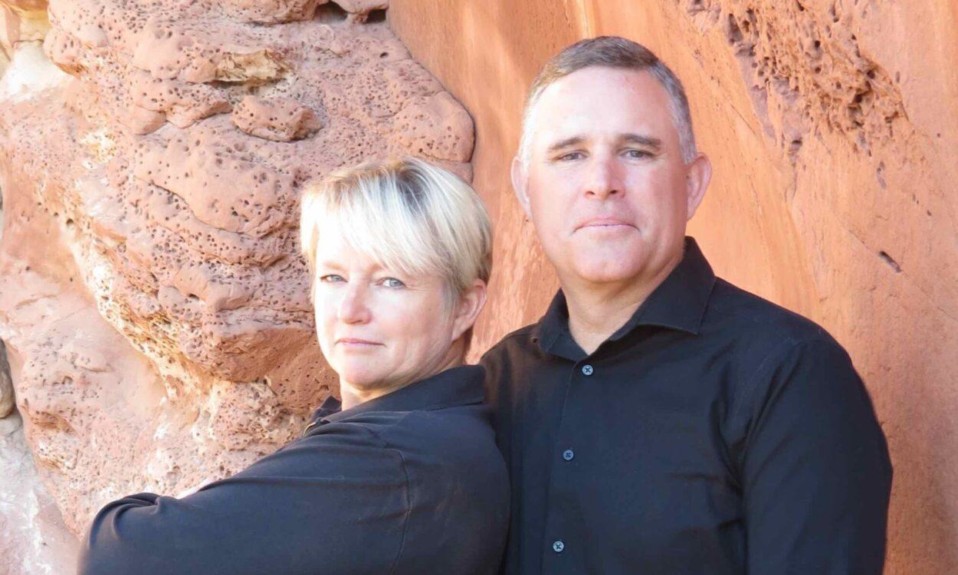

“The risk for me is too high,” says Dr. Bradley Peterson, MD, an emergency medicine physician at s. “Long-term care is not my specialty. Patients need to see a primary-care doctor who’s going to provide the necessary follow-ups to make sure their addiction is being treated appropriately by medication—not just by one busy ER doctor after another who refills buprenorphine for someone they’ve never met before.

“One in 20 opioid native patients get addicted to a narcotic prescription given to them in the ER. I don’t want to be the initial cause of a patient’s exposure, and I’m aware that I’m not the right doc to get them better once they have an opioid addiction,” Peterson says.

Legislators have made some progress in addressing the need for qualified buprenorphine prescribers, and more may be on the way. The Opioid Workforce Act of 2019 is intended to increase the number of residency positions eligible for Medicare reimbursements at hospitals with addiction or pain management programs. The bipartisan bill, introduced in May of 2019, has yet to pass the House of Representatives.