The dynamic of substance use disorder and Indigenous peoples is far more nuanced than meets the eye

By Jason Langendorf

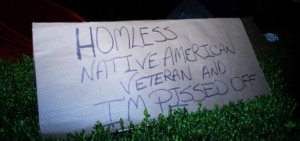

The rich, broad history of Native Americans, as told by non-natives, is too often short and sickeningly problematic. One of the few associations the average American often has with Indigenous populations, sadly, is their disproportionate suffering from the bane of addiction.

That isn’t to say the problem doesn’t exist. But in a 2015 study, Penn State researchers found that 87% of content about Native Americans taught to students in the United States includes only pre-1900 context, with significant portions of it dominated by “Eurocentric narratives,” inaccurate and damaging stereotypes, and portrayals such as the removal of Indigenous peoples being “an inevitable outcome of westward expansion.”

Anytime somebody comes along and says, ‘Hey, I can help you,’ it hasn’t come out that way. When I got here seven years ago, there was a lot of, ‘You’re bringing in the White Man’s medicine.’”—Kevin Markham, behavioral health director for the Muckleshoot Tribe

Based on the growing evidence demonstrating links between trauma and addiction, it would be easy to draw a connection: So much of Native American history has been twisted and whitewashed by those responsible for their genocide, colonization and cultural deprogramming that waves of generational trauma are driving a culturally skewed addiction crisis.

But that conclusion—like the mainstream Native American narrative itself—is too simple, falling short of a nuanced truth that ultimately can lead to solutions that best serve Indigenous peoples.

Native American Substance Misuse

A significant body of research shows that rates of substance misuse among Native Americans have been markedly higher than those of the general U.S. population. According to American Addiction Centers (AAC), 10% of Native Americans have a substance use disorder (SUD), nearly 25% report binge drinking in the previous month, and the population is more likely to report drug misuse in the previous month or year than any other ethnic group.

AAC identifies a variety of factors that contribute to these trends:

- Historical trauma

- Violence (including high levels of gang and domestic violence and sexual assault)

- Poverty

- High levels of unemployment

- Discrimination

- Racism

- Lack of health insurance

- Low levels of formal education

Although it’s a sensitive area to address, at least one more component might be at work: genetics. Some experts, rightfully, seem reluctant to open the door for outsiders to assign blame (and ignore other crucial risk factors) when analyzing the role of genetics in SUD. But according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, “scientists estimate that genes, including the effects environmental factors have on a person’s gene expression, called epigenetics, account for between 40 and 60% of a person’s risk of addiction.”

And from a key 2012 study from researchers at the University of Colorado: “It has been long known that some AI/AN [American Indian/Alaska Native] populations are less likely than Whites to have the protective variations of genes underlying the alcohol dehydrogenase/aldehyde dehydrogenase process essential for alcohol metabolism.” Are Native American populations, then, more predisposed to addiction than others? The short answer: It seems likely.

Providing Addiction Care to Native Americans

Unique challenges require specialized solutions. Experts in the addiction field emphasize the importance of culturally sensitive care in connecting with Native Americans in need of treatment. And because resources are typically found only off tribal grounds, or are from non-native sources, Indigenous populations may feel skepticism even when appropriate care is made available to them.

“I think a lot of it is distrust,” says Kevin Markham, behavioral health director for the Muckleshoot Tribe, based in northwest Washington state. “Anytime somebody comes along and says, ‘Hey, I can help you,’ it hasn’t come out that way. When I got here seven years ago, there was a lot of, ‘You’re bringing in the White Man’s medicine,’ ‘We don’t go to 12-step meetings’—things like that. We had to break through; we had to be compassionate and understanding; we had to be flexible.”

At the same time, the risk of painting Native American populations with too broad a brush—treating all citizens of every tribe, in every region, as a monoculture—is a mistake that only exacerbates the addiction issue.

The path forward for Native Americans suffering from addiction, most experts agree, is a combination of modern science, established best practices and a strong spirit of collaboration that ensures the specific needs of the affected population are being met.”

A 2012 article co-written by Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and published in The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse states: “Although national estimates show elevated substance abuse and related disorders for the [Native American] population as a whole, local and regional research indicate tremendous heterogeneity among AI/AN populations. Thus, it is important to understand that differences in urban/rural dwelling, tribal affiliation, linguistic and regional differences, gender, age cohort and level of acculturation to the mainstream American way of life make broad generalizations inappropriate.”

The path forward for Native Americans suffering from addiction, most experts agree, is a combination of modern science, established best practices and a strong spirit of collaboration that ensures the specific needs of the affected population are being met.

As Joseph P. Gone, professor of Anthropology and Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard University, wrote in a 2009 article published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology: “Consideration of this healing discourse suggests that one important way for psychologists to bridge evidence-based and culturally sensitive treatment paradigms is to partner with indigenous programs in the exploration of locally determined therapeutic outcomes for existing culturally sensitive interventions that are maximally responsive to community needs and interests.”

Effectively treating addiction among Native Americans will require a committed outreach to those communities. Active involvement of Indigenous peoples in the development and ownership of targeted treatment programs is the best way to ensure their proper care and to begin redressing some of the grave mistakes of the past.

Photos: Shutterstock