Karen Scott, president of the foundation, talks about the heavy lift of her mission and the headway that has been made in a short period of time

By Jenny Diedrich

Grim statistics confirm that America’s opioid crisis has only worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, driven by unprecedented social isolation and disruption in services, as well as the increased availability of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.

The Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE) is a private grant-making foundation that’s funding a group of diverse projects committed to bringing solutions to the crisis. Since its founding in 2018, FORE has provided $15 million in grants to numerous recovery-oriented organizations across the country, from the Addiction Policy Forum to Faces & Voices of Recovery.

“We continue to learn and be so impressed by people who see a need and are on the front lines trying to do what they can and make a difference,” says Karen Scott, MD, president of FORE. “When things are most effective, it goes back to starting by listening to the patient or the person with lived experience and really putting them at the center of the work.”

TreatmentMagazine.com talked with Scott about the current state of the opioid crisis and how FORE-funded projects across the country are having a life-saving impact.

Q: What is FORE’s mission?

A: FORE was launched late in 2018 as a brand-new national grant-making foundation. I believe we are the only national, private foundation that has a mission solely based around supporting solutions to the opioid crisis. We spent our first year creating a network of advisors from very different perspectives—from policy, front-line providers and people with lived experience—to help us identify where we can put the resources we have to really try to move the trajectory in addressing the opioid crisis.

As a foundation, we also understand that we need to think about the work in a very holistic way. We didn’t start off with an assumption that we were only going to put the foundation dollars toward one area. We need to have a holistic approach to how we think about opioid use disorder [OUD], and we need to incorporate an understanding that over the last 20 years this has become a crisis in many different communities across the country and to recognize how the crisis has changed over time. Most recently, that means that in the last couple of years the communities that have been most impacted by overdose mortalities are communities of color, particularly Black and Native communities. That reflects also the changing nature of the opioid crisis, in terms of moving from prescription painkillers to heroin and then fentanyl.

Q: What are some of the current statistics?

A: Just before the pandemic, we saw the beginning of a drop in overdose mortality between 2017 and 2019. But that’s been erased. The most striking, sobering statistic at the moment is that we surpassed 100,000 American lives lost due to overdose from 2020 to 2021. As you look within that 100,000, the populations where the overdose rate has gone up the fastest and the highest is for Black and Native [American] adults.

The opioid involved in many of those is fentanyl, which we know is extremely lethal, even in small amounts. We also know that the lethality of fentanyl itself in terms of potency continues to increase. It’s becoming more and more dangerous.

“The data points that really stand out to me are around comorbidities. I think it’s a really important message for us that OUD is not happening in isolation. Many struggling with an OUD are also already struggling with depression, anxiety or another behavioral health disorder.”

—Karen Scott, president, FORE

Q: What are some of the reasons the crisis is worsening?

A: We’ve seen a number of things happen, particularly in the early months of the pandemic. The isolation generated more people either relapsing or using drugs alone where [before] they might have been in more social situations with someone to rescue them. So many services were disrupted that many people lost their regular access to treatment or recovery services. We know it took a little while for telehealth or remote technology to replace some of those services. In some parts of the country, that never really happened. It also made it harder for people to start treatment. All of that was happening at the same time that the drug supply itself was getting more dangerous.

A couple of our grantees are doing a lot of data analysis for us. The data points that really stand out to me are around comorbidities. I think it’s a really important message for us that OUD is not happening in isolation. Many struggling with an OUD are also already struggling with depression, anxiety or another behavioral health disorder. All of those things just got worse within the last couple of years. When we start thinking about the longer term, it’s great that because of the pandemic there’s increased attention on mental health. We need to think about treatment and recovery interventions in a way that recognize that very few people have just one thing.

Q: What are some examples of how FORE’s grant-making approach is making a difference?

A: The first program we launched in March 2020 was a focus on supporting models to improve access to treatment for vulnerable populations. Underpinning all of our work as a foundation, we have prioritized how we can help support services that reach some of the highest-risk populations to have an impact in the short term, as well as which projects are going to provide important lessons learned. We’ve got relatively small dollars, but we look for the opportunities to provide learnings and resources to the much broader community.

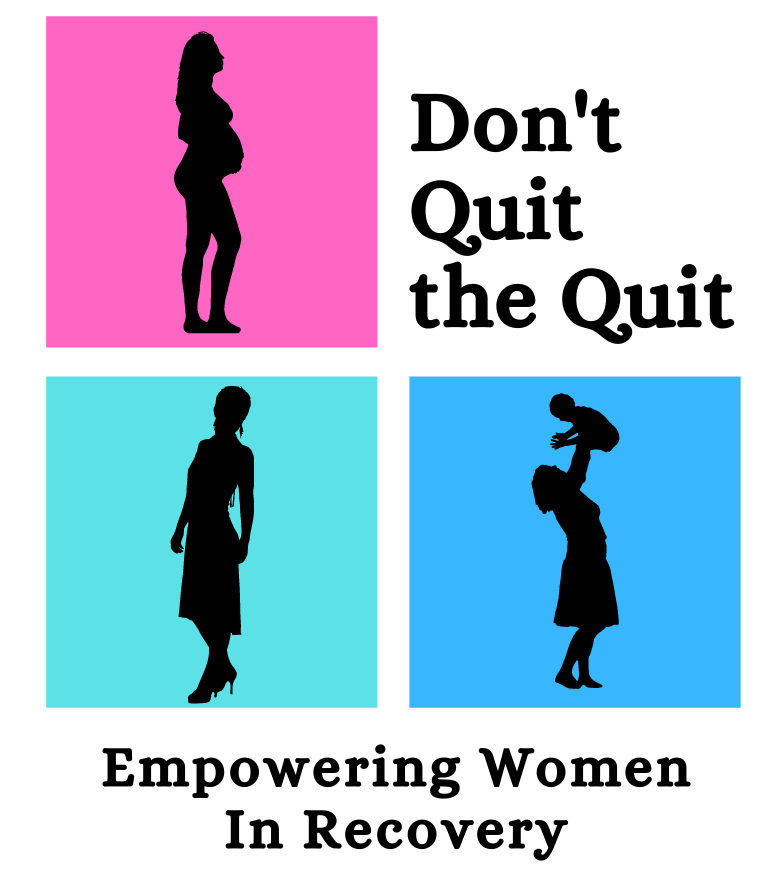

With the Access to Treatment program, we selected 19 projects and committed $10.2 million. That was our first round of grants. They are different types of projects around the country. A project with the University of North Dakota School of Nursing is called Don’t Quit the Quit. The project there focused on women they saw engaged in OUD treatment prenatally. They saw a rapid falloff in women sticking with treatment postpartum. At 12 months postpartum, we know women with an OUD actually have an increased risk for an overdose if they’re not in treatment. That’s the time period and the population they really wanted to target. They’re doing that by training women to be postpartum doulas. They’re doing it by educating staff at the local WIC [Women Infants, and Children] centers so the staff has information about local treatment resources. That program was recognized by the governor and first lady of North Dakota in the fall as one of the promising practices.

Another example is that we’re supporting a federally qualified health system in West Virginia called Cabin Creek Health Systems. They have developed a very comprehensive approach to supporting their patients with OUD. The centers are making sure there is availability of medication for OUD. They have prescribers who are trained to prescribe buprenorphine. They continue to work with their patients to build a comprehensive approach to providing medication treatment, counseling and connections to other services that their patients need in order to make it to recovery. As a federally qualified health center, they are working on the payment model to sustain the comprehensive services they’re providing. I’m looking at that as a model we’ll be able to share with other health centers around the country.

“We have some very exciting projects around bringing data together to look at different approaches to identify much more quickly what’s happening in a community and target responses.”

—Karen Scott

We added to our portfolio with some smaller grants starting in the summer of 2020 in response to what we were hearing were gaps during the first few months of the pandemic. For the foundation, we are in very regular contact with our grantees as well as with other advisors. We view our grantees as our partners. We listen to them, and that’s part of how we shape our next programs and our funding.

Q: Just this week, FORE announced $4.8 million in new grants. What is the focus of those?

A: As someone who did not spend my whole career focused on substance use, I keep hearing that it always seems to come down to these longstanding barriers around stigma and bias. Or the challenges with data and waiting months and months for perfectly clean numbers to come from the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]. By the time they come, how is that helpful to a city that is trying to respond right now to overdoses?

That led to several advisory discussions and a call for projects to think differently about those topics. One of the things that was of interest to me was trying to use funding to encourage different disciplines or agencies to work together. These wouldn’t be grants for only one department, but who else could they bring in to help think differently? That led to our Innovation RFP [Request for Proposals], which we put out last May. We received 479 responses and went through a very extensive review process. From that, we’ve selected 11 projects that will make up the core of our innovation work.

We tried to choose projects that would not only provide more immediate impact in the population they work with, but also some promising approaches and ways of thinking. If they work, they could spread to other parts of the country and provide information, tools and resources. We have our first project supporting training nurses. Another is around communication to address the stigma and bias. We have some very exciting projects around bringing data together to look at different approaches to identify much more quickly what’s happening in a community and target responses.

Top photo: Shutterstock