We spoke to the U.S. team’s sports psychiatrist about his role in Beijing and what can be learned about behavioral health in general from the experiences of elite athletes

By Jenny Diedrich

Mental wellbeing is increasingly being recognized as a key part of the equation for elite athletes. It should come as no surprise, then, that Team USA will be providing mental health support to its participants in the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, which begin on Feb. 4.

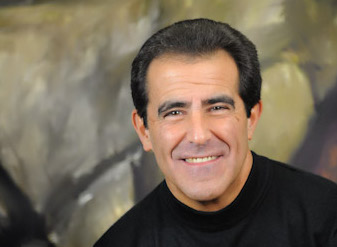

The U.S. Olympic Committee is bringing David Baron, DO, senior vice president and provost at Western University of Health Sciences, to Beijing to serve as Team USA’s sports psychiatrist. He will stay with Team USA in the Olympic Village. Baron has had a long relationship with the Olympics, dating back to the Los Angeles Games in 1984, when he administered psychiatry services related to doping control and anxiety issues to athletes.

The mental health component in sports has come a long way since then. “Thanks to incredible Olympic athletes like Michael Phelps, Simone Biles and others, the stigma often associated with mental health issues in the Olympics is lifting,” Baron says. “I’m interested in and encouraged by the increasing global awareness of the importance of mental health in healthcare.”

Before Baron headed off to Beijing, he spoke to TreatmentMagazine.com about psychological services in sports and what the general population can glean from high-level athletes who speak out about their behavioral health issues.

Q. Is the focus on mental health in the Olympics a new development?

A. Until fairly recently, mental health was something athletes didn’t talk about. It showed a weakness or a flaw. In the past, individual sports had a psychologist who would work with performance. This is a relatively recent phenomenon where the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee has really made a commitment to have behavioral health people on staff.

“In the sports world, every athlete, particularly when they get to the elite level, knows the difference between the gold medalist and the person who doesn’t get on the podium. It’s usually not the physical ability.”

—David Baron, Team USA sports psychiatrist

I truly believe it is the athletes who deserve the credit. They started to say, “This is an important part.” It took awhile until the marquee people came out and said, “It’s okay to not be okay, and we need to address this.” It’s been a slow evolution. In the past, athletes kind of dealt with this in silence and were very cautious about who they discussed it with. Now the world of sport is realizing that optimal performance includes not only the physical—a big part is [also] the mental health piece.

Q. Why is mental health so important in sports?

A. There’s an old saying that there is no health without mental health. And it’s really true. When we look at overall health, part of the stigma of mental health has been that we’ve always kind of walled it off. If you had a psychiatric illness, you went to a special psychiatric hospital. There is still prejudice about substance abuse and mental illness.

In the sports world, every athlete, particularly when they get to the elite level, knows the difference between the gold medalist and the person who doesn’t get on the podium. It’s usually not the physical ability. If you would measure physical ability, most of them are very close. You saw it in the Olympic trials in the 500-meter speed skating. The young woman who was No. 1 in the world on the day of the Olympic trials had a tiny little slip and took third, even though she was clearly the best. On that day, it was that anxiety. It happens with sports.

[Athletes] don’t want to call it mental health because that smacks of being depressed or having to see the shrink, but they know it’s that mental toughness. It’s that ability of an athlete to block out everything and just be laser-focused. You see that with the bobsledders. Before they go down, the person driving the sled has literally run that race in their head before they even take off.

I really feel for these current athletes. COVID has put a gigantic magnifying glass on [them]. For many of them, this is the pinnacle of their athletic career. COVID has been an incredible strain because you just don’t know. Anxiety is, in essence, the fear of the unknown. We get anxious about things where we anticipate a negative outcome or can’t control it.

Q. So is an athlete’s mental health just as important as physical health?

A. Mental health is one piece of that puzzle in overall health. For some individuals, it can be a larger piece of the puzzle, and for some a slightly smaller piece. COVID has shone a bright light on the role of anxiety and also the things that go on in life. What goes on in our lives is part of our overall health. Life still goes on even when you’re an elite athlete.

As a sports psychiatrist and a trained physician, I understand and know what’s going on with recovery from injury, but also how they’re impacted by the emotional. When we work with NFL players after being on injured reserve, they ask, “Am I ever going to make the team again?” It’s really at all levels, down to the Little League player who doesn’t want to strike out in front of Mom or Dad. It’s not only symptomatic anxiety and stress, but it also can turn into depression and other illnesses.

I’m thrilled to be able to help take care of the whole athlete, whether it’s physical or mental. If someone is coming back from a minor sprain and needs to compete in three days, you need to do all the physical and orthopedic things, but then how are they feeling about it? It’s just one piece of that bigger puzzle—not the only piece, but a piece that’s worth exploring.

Q. What can we learn from athletes like Phelps and Biles, who have spoken publicly about their mental health?

A. When he was a kid, Michael Phelps had ADHD. [His mother] got him into swimming to deal with some of his hyperactivity, and he turned out to be probably the world’s greatest swimmer. With ADHD, there are common comorbidities with anxiety, depression and substance abuse. He went through periods where he had those classic comorbidities. In more recent years, he talked a lot about that. Other athletes say, “If Michael Phelps can come out and say it’s okay [to confront and speak out about mental health], then it’s probably okay for me.” You see that in sport a lot. Sports figures become idols and role models.

“Now with COVID and the stress and anxiety, one of the potential silver linings of this very dark global cloud will be an appreciation that you don’t have to be ‘crazy’ to have life stresses affect you and the way you think, feel and behave.”

—David Baron

With Simone Biles, here is probably the world’s greatest gymnast. There aren’t enough superlatives to say how she’s pushed the envelope of what one can do in gymnastics. In gymnastics, the training is grueling. She had primed and prepared herself to compete in 2020 and then get on with the rest of her life. That got put on hold. Then you had COVID, which affected the training schedule for all athletes. You saw this incredible combination of unbelievable expectations and a whole host of things building up. The emotional literally affected the physical. She set a terrific example. You have to listen to your mind and your body. The message is that it is important to deal with all the stresses that come on.

It took courage, and I applaud all the athletes who have come out and said, “Hey, I’m still the best of the best and I deal with these things. I get help, and it has made me better.”

Q. Do other countries have the same focus on mental health in sports?

A. It varies with the country. We have colleagues from around the world, and I mentor a number of sports psychiatrists in countries where this is just coming out. There are countries where there is still significant prejudice and lack of understanding of mental health and drug and alcohol issues. Clearly, we’re seeing an expansion. The number of teams that have sports psychiatrists is small but growing. Everyone knows Michael Phelps and Simone Biles, not just in the U.S. but globally. It’s a work in progress.

We’re also seeing now the role of social media. The world is so interconnected. Something happens in an Eastern Bloc country, and the whole world knows about it in minutes. Social media can connect in a way that didn’t happen 20 years ago. That will hasten the process. Now with COVID and the stress and anxiety, one of the potential silver linings of this very dark global cloud will be an appreciation that you don’t have to be “crazy” to have life stresses affect you and the way you think, feel and behave.