Programs in North Carolina and Alabama are filling a major gap by teaching clinicians how to administer OUD medications

By Jenny Diedrich

Opioid use disorder (OUD) has continued to spiral out of control during the COVID pandemic, partially because just a small number of the afflicted actually undergo treatment.

In the past year, only about 20% of people identified as having an OUD have received treatment, according to Karen Scott, MD, president of the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE), which provides grants to organizations that are working to combat the opioid epidemic. “The data continues to show a tremendous gap between people with an OUD and those who make it to treatment and for whom that treatment provides effective, evidence-based medications,” she says.

“As our grantees are showing, primary care providers need training, mentorship and coaching to build a community of practice in which clinicians can provide high-quality, effective care to patients with OUD.”

—Ken Shatzkes, senior program director, FORE

But FORE is seeing progress in closing that gap through two programs it initially funded in March 2020 that are addressing a main barrier to treatment: the lack of primary care providers who are trained and experienced in treating patients with OUD using medications such as buprenorphine. The programs, in Alabama and North Carolina, have developed effective models for training primary care clinicians. “What our grantees are finding is that primary care providers really benefit from and appreciate ongoing mentorship and guidance from specialists in addiction medicine,” Scott says.

In North Carolina …

In North Carolina, Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) and the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill are working together to train primary care providers and staff at 15 community health centers and clinics. According to FORE’s data, MAHEC and UNC have offered training and technical help to more than 1,400 healthcare professionals across the state.

“[MAHEC and UNC] have significantly expanded the capacity for people to walk into a clinic and have someone there who can treat them with medications for OUD [MOUD]. They have provided everything from the initial introduction to treatment with medications for OUD to ongoing [assistance] available by video or by phone to consult around specific cases,” Scott says.

The work of MAHEC and UNC has helped to fill a major void. Says Maryshell Zaffino, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Ridge Health, which is a participant in MAHEC’s training program and serves more than 50,000 patients in western North Carolina: “In many of our counties, we’re the only place where people can afford the treatment they need.”

In Alabama …

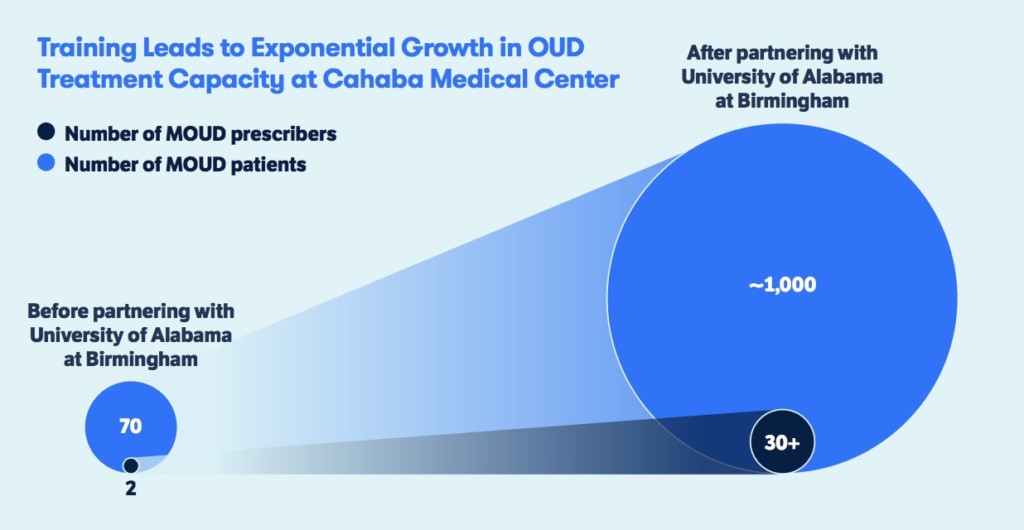

The second project is spearheaded by Li Li, MD, PhD, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurobiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In a state with a pronounced shortage of MOUD prescribers, she has trained more than 100 clinicians, including about 30 from Cahaba Medical Care, which has several locations in Alabama.

“[Li] has provided that virtual hallway consultation to the primary care doctors,” Scott says. “They all have her cellphone number. They can text or call her if they have a patient in front of them and aren’t sure what the next step is in terms of their treatment or have questions about increasing a dose of buprenorphine. What she finds is the phone calls decline over time as the clinicians get more comfortable and see more patients.”

The Overall Impact

Scott believes the type of ongoing mentorship that these two programs provide is critical to building an effective primary care network for treating OUD. “This will be an important additional component for us as a country to continue to put in place. Regardless of where [patients] walk in for care, they have a chance of being met by someone who can help them with treating an OUD,” she says.

“We’re so excited by what they’ve been able to accomplish, in spite of COVID.”

—Karen Scott, president, FORE

Given the success of the programs so far, Scott is hopeful about the future. “[The programs are] very far along in meeting objectives in beginning to build a primary care network of treatment providers,” Scott says. “We’re so excited by what they’ve been able to accomplish, in spite of COVID.”

Or as Ken Shatzkes, PhD, senior program director for FORE, puts it in an issue brief on the programs, “We are learning that merely getting waivered to prescribe MOUD is not enough to drive significant increases in access to care. As our grantees are showing, primary care providers need training, mentorship and coaching to build a community of practice in which clinicians can provide high-quality, effective care to patients with OUD.”

Top photo: Bruno Rodrigues; graphic: FORE