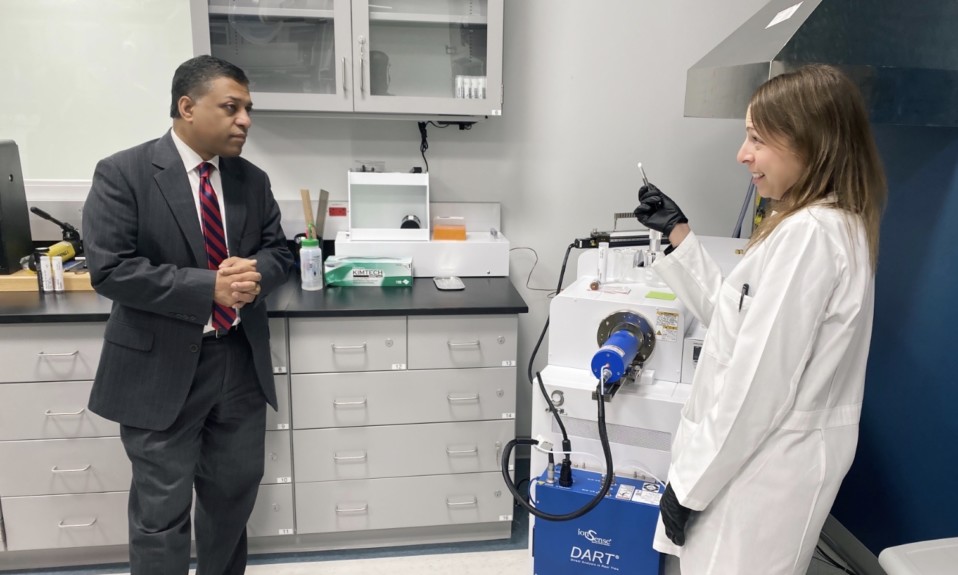

Emily Neely is using a fellowship from Equal Justice Works to help low-income West Virginia families that are in recovery navigate their legal issues

By Jenny Diedrich

Navigating the court system in opioid-impacted child custody cases can be especially challenging for people in recovery, threatening their progress and potentially triggering a relapse.

Emily Neely, a West Virginia native and 2021 graduate of the West Virginia University College of Law, is supporting people in recovery in her home state, an area of the country that’s been hit particularly hard by the opioid epidemic. Through an Equal Justice Works fellowship, Neely works with families in recovery to understand and resolve their legal issues.

“We’re offering an alternative so people in recovery don’t have to go through the pressure of court,” Neely says. “Putting them in a confusing environment can be triggering and very stressful.”

Her program, which is funded by the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE), provides alternative dispute resolution services to low-income families in which a biological parent is suffering from substance use disorder. She’s also creating a referral network with established recovery support programs and other organizations.

TreatmentMagazine.com recently talked with Neely about the development of the program and the benefits of alternative dispute resolution for people in recovery.

Q. How was your program created?

A. I was introduced to Equal Justice Works, a national organization that provides funding for public interest work, during my first year of law school. I was told about their Rural Summer Legal Corps program, which was trying to place summer fellows in different rural communities across the country. Luckily, they had a placement in Martinsburg at Legal Aid, where I work now. I had volunteered with Legal Aid during undergrad because I knew I wanted to be a lawyer and serve low-income families.

As graduation from law school got closer, I started to think about what I was going to do. I had learned that Equal Justice Works had a “design your own fellowship” program for graduating students. I thought I could create my own job, basically, and do it at Legal Aid. At the same time, I was in contact with an attorney in this area, and we were talking about how low-income families don’t have access to what’s called alternative dispute resolution. That means richer people can hire mediators and settle their disputes outside of court, but if you’re low-income, you can’t afford that. We talked about how that was not equal access to justice, and that was bothersome to us.

“Because West Virginia, unfortunately, is an epicenter for the opioid epidemic, we have a lot of people going through recovery. I realized something that could be helpful was reconnecting people in recovery with their children, as long as it was safe.”

—Emily Neely

I talked to Legal Aid about potentially having a program like that, and they were receptive to it. We discussed what the need in Martinsburg really was. Because West Virginia, unfortunately, is an epicenter for the opioid epidemic, we have a lot of people going through recovery. I realized something that could be helpful was reconnecting people in recovery with their children, as long as it was safe.

Equal Justice Works helped me connect with FORE, and they were kind enough to fund this project. It’s been wonderful to see that people are supporting a holistic approach, rather than forcing people through the court system, which adds pressure and stress to their already difficult recoveries.

Q. What are the benefits of alternative dispute resolution, especially for people in recovery?

A. Opioid use disorder can really break up families, and children end up with their grandparents. There can be resentment and emotional issues. We help reconnect people in recovery with their families. We have them all sit down in a room and talk about what this has meant for them. Additionally, we want to reduce trauma to children who have been separated from their parents. It’s well known that children need their parents in order to be healthy, happy and have a successful development. We want to reduce trauma to the children.

People in recovery often represent themselves in court. It’s very scary for them. The terminology that’s used—they don’t fully understand what’s happening, and it all goes very quickly. There’s procedure they’re not trained in. It’s all kind of a blur, and next thing they know, they don’t have access to their kids anymore. For someone in recovery, that’s huge. It’s an extremely stressful event that can trigger relapse.

“One of the wonderful things about mediation is you can always come back if other issues come up.”

In court, it’s up to the judge. The judge decides the schedule and has full control over what happens. With mediation, the individuals have control over their own schedules. They make a parenting plan that works for them, and they can always change it as they get further into their recoveries. There’s a sense of control and of hope. They’re making progress.

A lot of times when grandparents get the children, they’re missing information like social security numbers, and it’s hard for the grandparents to help the children get to school or therapy. Offering a mediation service can help the grandparents reconnect with the person in recovery and get that information. It’s a very holistic approach.

Q. Can you share a mediation success story?

A. My first mediation was a young woman in recovery who was kind of on her own. Her boyfriend was incarcerated and not able to help her. The children’s paternal grandmother had filed for guardianship of the children, and it was not the first time she had to do that while the mother was getting back on her feet. She had two children and really wanted to get her children back. She had just gotten her own apartment and was doing well in recovery. The grandmother said, “I want to support her recovery. I care about her, but I am concerned that having both of them back right now will be too much for her to handle all at once.”

They agreed to come to mediation. They recognized that it was a difficult situation and that they cared about each other. The grandmother said, “I want you to have your kids. I’m just worried.” The mother was able to be receptive and say she appreciated that. We came to an arrangement that she would get one of her children back full-time, with the grandmother supporting her as necessary. If that went well, she would be able to get the second child back. Of course, the children were still able to see each other. It was an arrangement that they both were comfortable with. One of the wonderful things about mediation is you can always come back if other issues come up.

Q. Why is this service so important in West Virginia?

A. I remember [being an] undergrad when The New Yorker released an article specifically discussing Martinsburg as the worst place in the country for opioid use. That was very striking to me because this is where I grew up. I’ve been here since I was 8. I’ve also seen it in person. I’ve seen people on the streets and have had members of my high school who overdosed. It’s something that I’ve grown up seeing and knowing.

“I would really love to see more people taking advantage of the program. I’d also like to expand our reach statewide.”

It’s difficult, because West Virginia is such a wonderful state and has so much to offer, but this is something we get labeled for. I really want to change that, and I want people to see this as a place not just where people are using opioids, but as a place they can get services they can’t get otherwise.

Q. What are your goals for the future of the program?

A. I would really love to see more people taking advantage of the program. I’d also like to expand our reach statewide. Right now, we’re focused on the five counties this Legal Aid office serves. I’d love to see Legal Aid be a pioneer in that way. I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity and to Equal Justice Works and FORE for all their support. I hope to see this expand and grow. It’s what I’ve always wanted to do.