Hampered by stigma, self-mutilation is attracting more attention and support, due in part to the rise of telehealth

By Jason Langendorf

January 5, 2021Self-harm addiction—be it cutting, deep scratching or some other wound—is often tough to see from the outside, and to talk about when you’re inside of it.

Amanda Beausoleil had the sort of childhood that would have appeared, to anyone looking from the outside, to be nothing short of charmed. Growing up in Katy, Texas, a suburb of Houston, in the 1990s, she was a cheerleader—captain of the team, no less—in the heart of football country. She was a typical kid, did well in school. Both parents at home. Plenty of friends. A vibrant social life. What she didn’t have was an outlet for her most complicated emotions.

Beausoleil remembers the moment, when she was 10, she discovered her outlet. She was angry and upset, and went to the bathroom to be alone. It gave her cover in case she wasn’t able to hold back her tears, which in her home were considered an unnecessary drama: weakness.

That’s when she began scratching her face.

“I remember the first time, and it was natural. It just felt like second nature—somehow I already knew how to do it,” Beausoleil says. “And no, I didn’t learn it from anyone. I don’t remember seeing it on TV at the time or anything like that. I just remember I was upset about something—I have no idea what. And in my household at the time, crying was looked down upon. It was kind of like, you know, a ‘suck it up’ type of thing.”

She remembers the relief that washed over her, how the blood felt, in a way, like tears. Beausoleil says she was able to “go through the emotions while in the state of harming myself, and relax myself.” The act, she says, made her feel normal again. It gave her an outward expression, finally, of what she felt inside. It gave her control.

Research and Scholarship on Self-Harm

Documented cases of self-injuring can be found as far back as biblical times, according to Bodily Harm: The Breakthrough Healing Program for Self-Injurers by Karen Conterio and Wendy Lader, Ph.D., and published in 1998. It’s still one of the definitive early texts on the subject.

In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published in 2013, self-injury is classified as a “new disorder in need of further study.” It may be referred to as self-harm, self-mutilation or non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), among other terms. It may be called an addiction, a condition or a behavior. When diagnosed or detected, it’s often misinterpreted or avoided altogether by friends, family, teachers and even caregivers.

What We Know About Self-Harm

Self-harm takes many forms

Self-harm can manifest in a variety of ways. People who injure themselves may cut, puncture or burn their skin, using any number of implements. In some cases, self-injurers go to greater extremes, breaking bones or even injecting themselves with toxins.

Self-harm is not suicidal

People who injure themselves aren’t dabbling with the notion of suicide or otherwise inviting death. It’s an isolating disorder that is uncomfortable for many on the outside to confront, leading to further isolation for the person suffering from it.

Self-harm and abuse

In some cases, self-injurers have experienced abuse or trauma. They are often diagnosed with an underlying condition, including depression, bipolar disorder, psychosis, multiple personality disorder or borderline personality disorder.

Self-harm and adolescents

Self-harm tends to be viewed as an adolescent condition, one that affects girls and women more often than boys and men. Both characterizations, however, are coming under increased scrutiny, in part because of low reporting numbers.

Self-harm and stigma

The stigma associated with self-harm is as weighty as that surrounding any addiction, if not more so. As Conterio and Lader define it, self-injury is “a way of managing emotions that seem too painful for words to express.” People who self-injure, like Beausoleil, often describe the act as a release. Many are ashamed of the behavior. Others are proud of it, viewing their scars as a sign of their tolerance to pain or their agency in the world. Some may oscillate between the two ways of thinking, or feel a combination of both.

Self-Harm Support and Solutions

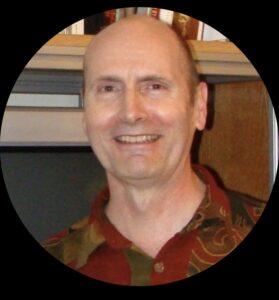

James M., 69, is the president of Self Mutilators Anonymous (SMA), an organization he co-founded in 1986, when it began holding group therapy sessions designed as self-harm’s answer to Alcoholic Anonymous’ 12-step program. For the first 10 years of SMA’s existence, he says, all of its regular members were 40 and older.

James M. recalls speaking about the subject with Armando M. Favazza, M.D., a pioneering psychiatrist, editor, professor and author in the field of self-harm, in a phone conversation around the same time.

“I remember the whole idea of gender participation came up, and the stereotypical thought was only women did it, or dominantly women,” he says. Dr. Favazza disagreed. “Statistically, what his research was saying was it was 50-50, but that men were far less likely to come forward and admit it. Just like back in the ’40s, women were far less likely to join AA than men because of the social stigma.”

The AA-SMA connection is palpable for James M. After finding sobriety from alcohol through AA, he began scratching his scalp to the point that it would bleed, leaving sores. He didn’t initially understand the compulsion, and even after learning more, he found no support group for self-harm. So he, along with a co-founder, Shelley, created their own community. More than three decades after establishing SMA, James says self-injury has been the toughest of his addictions to control.

“I have three, and alcohol was a breeze. To get over sex—the other addiction I have—that’s probably five times harder than alcohol. And this,” James says of self-harm, “is probably three times harder than sex to get sober [from].”

Self Mutilators Anonymous Today

Under normal circumstances, the Self-Mutilators Anonymous support group meets twice a week, on New York City’s west side in Manhattan near Columbus Circle. By necessity, SMA has become a telesupport community. This was an initially frustrating concession made to the pandemic.

But the unintended, remarkable consequence has produced a surge in the organization’s unofficial membership, with participants joining video-conferencing calls (which SMA began in 2018) from all corners of the globe. The supercharged access and additional layer of anonymity have connected with more self-harmers.

Beausoleil, now 29, who after years of feeling shame and stigma (even from some of her own clinicians) and accepting that she had to “figure it out on my own,” attended her first SMA meeting around six years ago. It was a revelation.

“It was December,” she says. “It was snowing. It was freezing. And I was just crying in the middle of the street, just joy. Because I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I think for the first time, I’m gonna be OK.’ Like, ‘I can beat this. It doesn’t have to be with me for the rest of my life.’ Because it really did define me.”

Devoting herself to the program, Beausoleil became so interested in helping others like her that she eventually approached James about a role with SMA. (“He was almost in tears,” she says. “He’s like, ‘I’ve been waiting 30 years for you.’”)

Now the vice president of SMA, Beausoleil is in charge of finalizing a business proposal, seeking outside funding to grow the program and updating the organization’s literature. That won’t include, she says, rethinking the name of Self Mutilators Anonymous.

“People have asked James and myself to change the name so many times,” Beausoleil says. “And even before my time, people have asked James to change it—and he refuses. And I understand and agree with him.

“The reason we don’t change it is because it is mutilating your body. This is something that’s already swept under the rug, so ‘self-harm’ sounds too soft, like, it’s a slap on the wrist. You’re not like, ‘Oh, you bad little thing.’

“You are destroying your body. That’s the problem. So let’s address it for what it is. In order to destigmatize it, we ourselves can’t be afraid of the word.”

If you are self-injuring and would like to seek help or support, you can contact Self Mutilators Anonymous. If you are experiencing a mental health or substance crisis, contact SAMHSA’s 24/7 National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).