Plus: Fewer Americans think drug addiction is a big problem, and how virtual reality can reduce post-op opioid use

By Mark Mravic

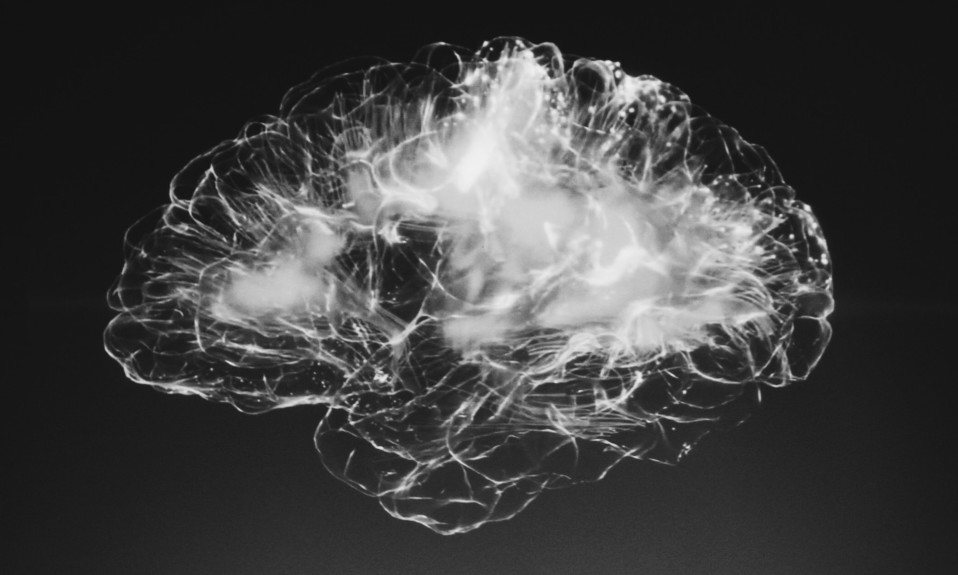

Can the brains of stroke victims unlock important information about addiction, and possibly provide the neurological key to treatment? Studying cases in which people who suffered strokes suddenly lost their craving for nicotine or alcohol, a transatlantic team of researchers say they’ve mapped a network in the brain that is intimately involved in addiction—and remission.

Also this week, some puzzling Pew Research numbers on Americans’ perception of the drug crisis, and how VR gaming can help patients manage pain and ease opioid prescribing.

From Nature Medicine:

Stroke Damage Reveals the Brain’s Addiction Circuit

Scientists have long observed that heavy smokers who suffer a stroke or other brain injury sometimes immediately lose their craving for cigarettes. Past studies associated this phenomenon with stroke-caused lesions on part of the brain called the insula. But findings were ambiguous: Some people whose strokes damaged the insula did not lose their addiction, whereas others whose strokes injured areas outside the insula did.

Researchers from Harvard, Finland’s University of Turku and elsewhere sought to reconcile these results and find out what’s really going on. In a study published last week in Nature Medicine, the team looked at the brain scans of 129 smokers who’d suffered a stroke or other brain lesion; of those, 69 continued smoking afterward, but 34 were able to quit immediately and reported no subsequent craving. The researchers, rather than focusing on a specific region of the brain, pulled back to examine the bigger picture using a map of brain networks called the human connectome. In doing so, they found that it was a brain circuit—essentially a series of connected hubs within the brain—rather than an isolated locale that was associated with the loss of nicotine craving. Damage to areas along this circuit, which included the insula as well as other parts of the brain, was associated with the loss of craving; injuries occurring outside of the circuit did not eliminate that craving.

Especially intriguing is that the circuit appears not to be specific to nicotine addiction. Further data showed that a reduced risk of alcoholism after a stroke mapped onto a similar brain circuit. It suggests this craving-related brain pathway may be involved in general addiction—offering the promise, down the road, of treatments such as brain stimulation that target the circuit not just for smoking or alcohol use but for a wide variety of substance use disorders.

“This could be one of the most influential publications not only of the year, but of the decade. It puts to rest so many stereotypes that still pervade the field of addiction.”

—A. Thomas McLellan, former deputy director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, to The New York Times

“By looking beyond individual brain regions and, instead, at the brain circuit, we have found targets for addiction remission and are eager to rigorously test them through clinical trials,” said Michael D. Fox, MD, PhD, Harvard Medical School associate professor of neurology, one of the study’s authors. “Ultimately, our goal is to take larger steps towards improving existing therapies for addiction and open the door for remission.”

But the impact of this study may go beyond its potential for treatment—it could also help in reducing stigma by further reinforcing that addiction is indeed a disease of the brain. “I think this could be one of the most influential publications not only of the year, but of the decade,” A. Thomas McLellan, professor emeritus of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and a former deputy director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, told The New York Times. “It puts to rest so many of the stereotypes that still pervade the field of addiction: that addiction is bad parenting, addiction is weak personality, addiction is a lack of morality.”

From Pew Research Center:

Has America Stuck Its Head in the Sand on the Drug Crisis?

In 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 71,595 people died of drug overdoses in the U.S. In February of the following year, Pew Research Center surveyed Americans and found that 42% said drug addiction was a major concern in their local community. By 2021, annual overdose fatalities had soared to 107,891—a shocking 51% increase in four years. Yet last fall—as each month brought a new record for overdose deaths—Pew found that the percentage of Americans who viewed addiction as a major problem had actually dropped by seven percentage points in the intervening years, to 35%. Moreover, in a separate Pew survey in January 2022, drug addiction ranked lowest out of 18 policy priorities for the federal government to address.

The counterintuitive findings ranged across the board—results were similar in urban, suburban and rural communities, all of which have seen notable increases in overdose rates. Moreover, both in areas where overdose rates are above the median and in areas where the rates are increasing fastest, the share of people who say addiction is a major problem fell by 6% to 7%.

“It’s not clear why public concern about drug addiction has declined in recent years, even in areas where overdose death rates have risen quickly,” the report notes. “Surveys by the Center show that Americans have prioritized other issues, including the national economy, reducing health care costs and dealing with the coronavirus outbreak.”

From JAMA Network:

Angry Birds vs. Opioids

The movement to manage pain and reduce painkiller use can take on curious forms, but whatever works is welcome. For instance, “virtual reality distraction therapy”—wearing VR goggles or headsets to deflect a patient’s attention during painful procedures like wound care or blood draws—has been in use in a number of settings. Researchers at the Oregon Health and Sciences University looked at whether VR can help patients who’ve undergone head and neck surgery not only cope better with pain but reduce their need for post-op opioids.

In a small pilot study, 29 patients hospitalized after surgery were asked to play Angry Birds while they recovered. The control group of 15 did so on smartphones; the other 14 were given Oculus Quest VR headsets, which provided an immersive 3D gaming experience. The results: Researchers found “clinically meaningful” reductions in pain scores for the VR group compared to the smartphone cohort at one, two and three hours after operation, and reductions in the amount of opioids used at four and eight hours post-surgery. “Optimal postoperative pain management is challenging,” the authors note. “Virtual reality may be a useful adjunct for postoperative pain management after head and neck surgery.”

Photo: Alina Grubnyak, Wolfgang Hasselm