We need to listen to and learn from each other to create a network of community-up recovery spaces

This post is reprinted with permission from one of TreatmentMagazine.com’s go-to blogs about addiction, treatment and recovery: Recovery Review.

By William Stauffer

The title of this post is inspired by Margaret J. Wheatley, Who Do We Choose To Be?: Facing Reality, Claiming Leadership, Restoring Sanity (2017). The book came up in a recent conversations I had with Phil Valentine of CCAR when we were talking about influential readings. He told me about it and suggested to me it was to be digested slowly. I am an avid reader and sat down to read it from cover to cover. The truth of his words became clear to me after a few pages. Wheatley talks about how all things—even societies, have life cycles and that ours was in a period where large scale change is not often viable. Our institutions have decayed in the current stage of our society that they are largely ineffective at broad systemic change.

She suggests focusing locally and developing leaders to create space to support healthy community. I confess to not yet having finished her book. Having read books like Putnam’s Bowling Alone, The Fourth Turning by Strauss and Howe and Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed by Jared Diamond, the topic is not new, but her focus (as far as I can see from about one halfway in) is to encourage leaders to develop and support community in ways that nurture people through difficult times. She calls these spaces “Islands of Sanity.” Quite a lot to digest. I will read it slowly.

Recovery history shows us we tend to move away from community-oriented solutions as programming becomes institutionalized. We shift to fee-for-service funding models focused on individual units of care, following a clinical mentality.

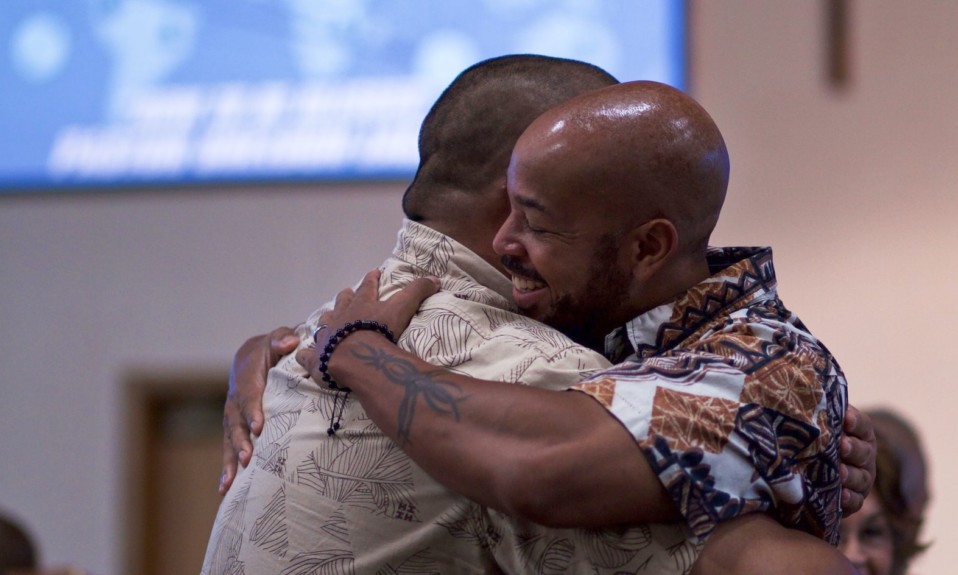

Many of us have experienced and are building such Islands of sanity in the recovery community. Recently in Punta Gorda, Fla., the CCAR Multiple Pathways of Recovery Conference was such a gathering of people from around the nation to nurture recovery community. I had a similar experience last fall at the Mobilize Recovery convening in Las Vegas. The Association of Recovery Community Organizations through Faces & Voices of Recovery is another similar space. A theme of the conversations with people at these events is what do we do next to support additional recovery communities—I would call islands of healing around the nation. I think history has a few lessons for us on what works:

- Communities can and do best self-define their own manners of healing. One of the well-known stories I have heard Don Coyhis, founder of White Bison and the Wellbriety Movement talk about is a conversation he had with federal grant officers when his organization was initially awarded funding to support recovery for indigenous peoples over 20years ago. He was told he had to use evidence-based practices in the grant. He noted that the Native American community had several thousands of years of evidence of what worked to heal their communities. Much to their credit, they listened not just to Don but to other recovery community organizations in including their own expertise in strengthening their own communities. In this way, these grants helped form these islands of healing across America through the SAMHSA the initial Recovery Community Support Project grants. These are community-up, not government-down solutions that can greatly benefit from the support of the government but must be led by the recovery community. Look at what was accomplished, the approach worked. CCAR and many other RCOs who formed at that time are evidence of this very dynamic.

- If we want to build community-based services that meet the needs of our recovery community, we have to design funding around what works for these communities instead of trying to adapt healing processes to existing funding mechanisms. Recovery history shows us we tend to move away from community-oriented solutions as programming becomes institutionalized. We shift to fee-for-service funding models focused on individual units of care, following a clinical mentality. Instead of developing a deep understanding of what actually works, community-oriented programing is thus altered to meet existing funding mechanisms. These funding processes tend to favor large entities not grounded in recovery community. Community based recovery organizations try and use these funding mechanisms to serve their missions, but it often becomes a challenge as the focus becomes chasing these limited dollars and narrowing their missions to get paid for service units designed for clinical services.

- There is great interest in the national recovery community to build additional communities of healing. Many of my conversations with leaders nationally end up focusing on what we can do to advance efforts to heal communities using a recovery community-up model. As I have mentioned in prior articles, I see a lot of room for consensus, but that the development of such consensus involves deep conversations, inclusivity and a lot of active listening. Readers of this post inside of government seeking ways to address our burgeoning addiction epidemic would do well to follow the wisdom of leaders like Dr. H. Westley Clark and the first grant officer of the SAMHSA RCSP grants, Cathy Nugent, who worked to bring these communities together and to start building these bridges of healing communities by listening to their experiential evidence of what works and helping to support them instead of redefining them to fit into some other model.

There are many of us across the county invested in building a care and support system that actually meets the needs of our respective communities. When I see the depth of interest in this issue, it brings me hope. Our mutual well-being will be largely dependent on how we can help nurture each other’s islands and support new islands built by people focused on healing their own communities. In a post titled “Creating a Broad & Inclusive Recovery Plank,” I recently suggested that developing broad goals is a good place to start strengthening such bridge building efforts.

Perhaps we should form a recovery island bridge building coalition of similar minded communities that want to understand and develop common ground in between our islands and build bridges that span our differences. Here are three points to start such a conversation:

- Recovery communities are the experts on what is needed in their own communities. Recovery communities are diverse, and our efforts must be supported and funded equitably designed by us to serve our own communities.

- Discrimination and stigma against us must end. Systems that tokenize us are perpetuating discrimination. It is not acceptable to tokenize our voices. There has to be an accounting for how this has happened historically to marginalize us in order for healing to occur and for our society to reap the full benefits that a recovery orientated model of care can offer.

- How we do things matters. Our recovery communities are quite often vulnerable, and there are many groups, including some run by people in recovery that take advantage of our own people for material gain. We must establish a shared set of values and ethics and adhere to them to protect the most vulnerable among us.

So, to all the bridge builders of islands of recovery community—let’s find ways to develop consensus and understanding of each other and our experiential wisdom. If you disagree with my three points, I would love to hear yours, if those of us invested in bridge building listen to each other in this way, we will identify a common pathway forward!

The truth is we do not need to have strong institutions to build consensus and community. We can do that with and for each other.

It is true that when we come together, we are stronger. It is also true that the history shows us that we are most effective when we do so, even as there are so many forces that keep us arguing over small things. The truth is we do not need to have strong institutions to build consensus and community. We can do that with and for each other.

Please consider being a bridge builder between recovery communities. The island you strengthen may well be your own!

This Recovery Review post is by William Stauffer, who has been executive director of Pennsylvania Recovery Organization Alliance (PRO-A), the statewide recovery organization of Pennsylvania. He is in long-term recovery since age 21 and has been actively engaged in public policy in the recovery arena for most of those years. He is also an adjunct professor of Social Work at Misericordia University in Dallas, Pa. Find more of his writing, as well as a thought-provoking range of articles, insights and expert opinions on treatment and addiction at RecoveryReview.com.blog.

Top photo: Erika Geraud; bottom photo: Alex Azabache