Lifting the “moratorium” on mobile components will help to provide more people with MAT

By Jason Langendorf

More people with addiction are expected to gain access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) thanks to a critical rule change implemented by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) this week.

The DEA announced on Monday, June 28, that it would no longer require registered narcotic treatment programs (NTPs) to file for separate registration of a “mobile component,” effectively ending the agency’s moratorium on approving new mobile treatment units, which had been in place since 2007.

“Today’s action by the DEA will improve access to life-saving medication for opioid use disorder [OUD], especially for those in underserved communities who face barriers to treatment,” Regina LaBelle, acting director for the Office of National Drug Control Policy, said in a statement.

According to 2019 data from the Federal Registry, only about 1,700 brick-and-mortar NTPs were registered with the DEA, and just eight of those were authorized to deploy mobile MAT units. As opioid overdose rates continue to spike in the United States, driven in part by the pandemic, the need has never been greater for connecting people with OUD to treatment solutions—especially in rural areas and inner-city communities where NTPs are fewer.

[This] action by the DEA will improve access to life-saving medication for opioid use disorder, especially for those in underserved communities who face barriers to treatment.”—Regina LaBelle, Office of National Drug Control Policy

Why Is MAT So Important?

The standard of care for OUD medication-assisted treatment consists of behavioral therapy combined with at least one of three Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug treatments: methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone. Methadone, in particular, has been overregulated and stigmatized, despite its effectiveness and the pressing need for OUD treatment solutions.

Concerns about diversion had kept the DEA from lifting the mobile unit moratorium, despite the accelerating opioid crisis and almost no evidence of MAT diversion tied to mobile units.

According to the Federal Registry: “A review of theft and loss reports from 2005 to 2017 shows that NTPs did not distinguish thefts and losses occurring at the registered location from those occurring at mobile facilities. There was only one report that concluded theft or loss occurred at a mobile NTP. … Furthermore, since 2017, there have not been any additional mobile NTP reports of thefts or losses of controlled substances submitted to DEA.”

Not only will people with OUD who are isolated in rural locales or stranded in treatment deserts in cities benefit from the DEA’s rule revision, but it will also help prison populations, which are affected by addiction in disproportionate numbers.

“They can get services right there, and then the folks are also connected with the service provider upon release,” says Beth Connolly, project director of the Substance Use Prevention and Treatment Initiative at Pew Charitable Trusts. “This is fantastic, because they’re receiving services while they’re in jail and then, upon release, are also connected with the same providers. The continuity is incredibly important.”

Why Now for Mobile Treatment?

The Biden administration has pledged to work toward removing barriers to treatment, and advocates such as LaBelle and Tom Coderre, acting assistant secretary for mental health and substance abuse for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), have helped make the case for removing red tape that prevents the application of safe and proven treatment solutions.

Now we have something else that we can say, ‘Look, here is yet another tool in the toolbox that will reduce the barriers to accessing medication.’”—Beth Connolly, Pew Charitable Trusts

In a roundtable discussion at the John Brooks Recovery Center in New Jersey highlighting the DEA’s rule change, Coderre—himself a person in recovery—could not have been more direct about the impact of improving MAT access: “People die if they don’t get these medications.”

Connolly cites additional policy adjustments around telehealth and methadone, along with new guidelines removing the “X-waiver” requirement for the administration of buprenorphine, as examples of barriers to treatment that have recently been removed.

“So now we have something else that we can say, ‘Look, here is yet another tool in the toolbox that will reduce the barriers to accessing medication,’” Connolly says. “So we’re really hopeful that this will actually increase the number of people who are receiving this life-saving treatment.”

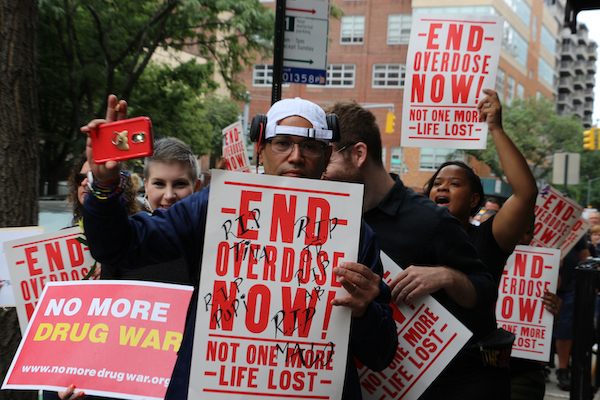

Photo: Joey Kyber