Researchers found variance in the reliability of devices, raising concerns about people mistakenly getting behind the wheel while impaired

By Jason Langendorf

May 11, 2021Fatalities related to motor vehicles are the leading cause of accidental deaths in the United States for all age groups under 75, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Many of those accidents involve alcohol.

Recently, the development of smartphone-paired devices designed to measure blood alcohol content (BAC) appeared to provide a tool for helping prevent alcohol-impaired driving. But in a study published this month in Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, investigators found enough variance in the accuracy of these devices as to deem them unreliable.

Some may use smartphone breathalyzers to see if they are over the legal driving limit. If these devices lead people to incorrectly believe their blood alcohol content is low enough to drive safely, they endanger not only themselves but everyone else on the road or in the car.”—M. Kit Delgado, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

“All alcohol-impaired driving crashes are preventable tragedies,” lead author M. Kit Delgado, M.D., an assistant professor of emergency medicine and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, said upon the publication of the study. “It is common knowledge that you should not drive if intoxicated, but people often don’t have or plan alternative travel arrangements and have difficulty judging their fitness to drive after drinking. Some may use smartphone breathalyzers to see if they are over the legal driving limit. If these devices lead people to incorrectly believe their blood alcohol content is low enough to drive safely, they endanger not only themselves but everyone else on the road or in the car.”

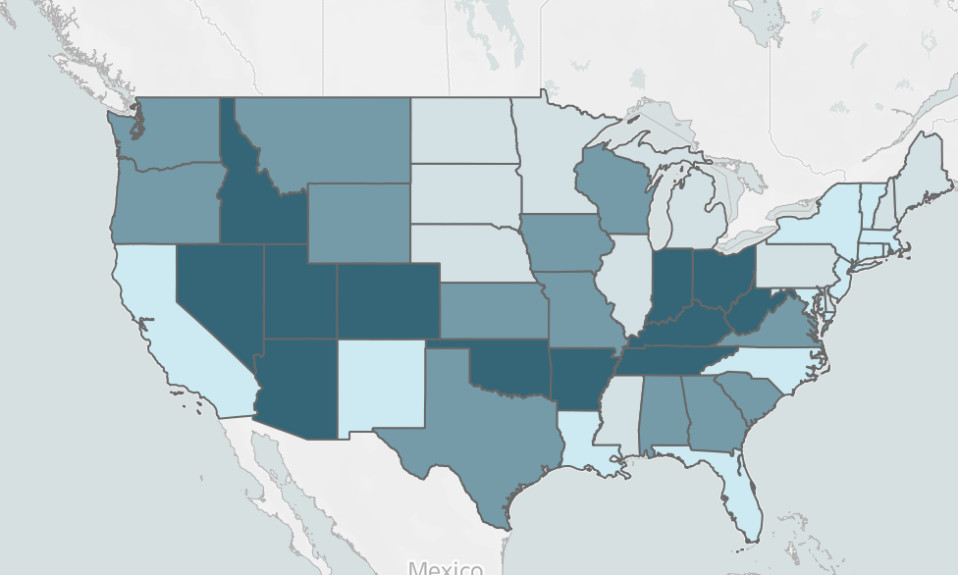

In 2016, more than one million U.S. drivers were arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol or narcotics, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In that same year, more than 10,000 people died in alcohol-impaired driving crashes, making up more than a quarter of all traffic-related deaths in the United States.

The Smartphone Breathalyzers Study

The Penn study included 20 moderate drinkers (ages 21-39), with participants receiving three “doses” of vodka over 70 minutes. After each dose, researchers measured the participants’ blood alcohol content using six smartphone-paired devices and a police-grade handheld device. For the most accurate reading of BAC, participants’ blood was drawn after the final dose. Researchers found that although some devices were more accurate than others, all of them—including the police-grade device—undermeasured the participants by at least 0.01 percent.

“The accuracy of smartphone-paired devices varied widely in this laboratory study of healthy participants,” Delgado and his co-authors write in the study. “Although some devices are suitable for clinical and research purposes, others underestimated BAC, creating the potential to mislead intoxicated users into thinking that they are fit to drive.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t currently require approval for this technology, according to Delgado. But, he said, “given how beneficial these breathalyzer devices could be to public health, our findings suggest that oversight or regulation would be valuable.”

Top photo: Per Loov; bottom photo: Esri Esri