For one, they make it clear that we need to retool our treatment apparatus

By Jason Langendorf

The latest preliminary U.S. overdose data is in, and it paints a bleak picture of the opioid crisis and the current state of addiction in America. Moreover, the trajectory of the numbers suggests the worst is yet to come.

More than 93,000 Americans died of a drug overdose last year, according to provisional statistics released last week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—the highest single-year figure ever recorded. The 29.4% increase in overdose deaths from 2019 is the largest one-year rise since at least 1999, Nora Volkow, M.D., director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), told NPR.

I think oversimplifying and pointing fingers at one area has been a mistake. To address [the overdose problem], we’ll truly need a multipronged approach.”—Lawrence Weinstein, American Addiction Centers

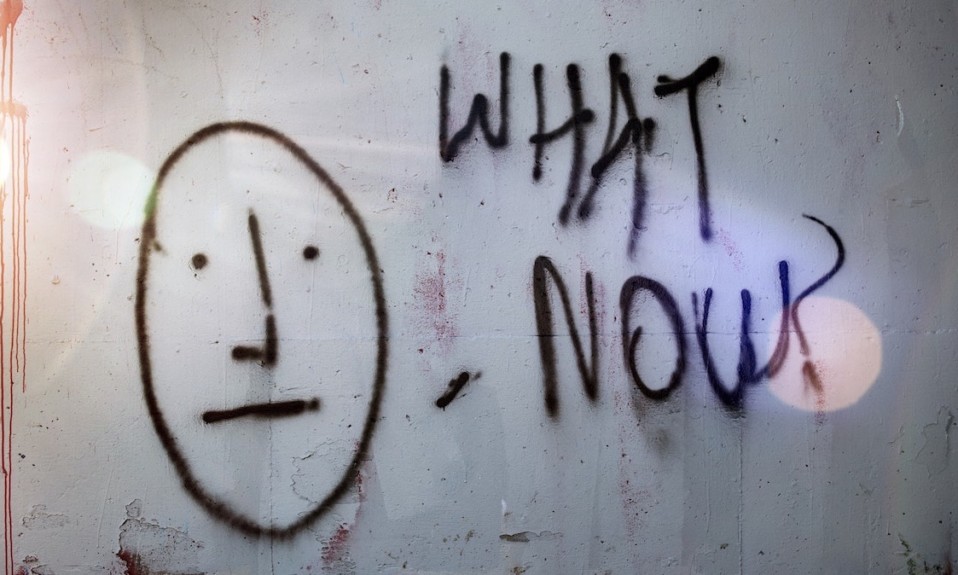

Many experts saw this coming. Given the withering circumstances brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic (isolation, anxiety, restricted access to addiction treatment) and the recent influx of fentanyl into the illicit drug supply, any such prediction was hardly wild speculation. But now that the numbers have confirmed those fears, the question becomes: What can be done about it?

Exploring Treatment Improvements

Last week The Pew Charitable Trusts released an issue brief detailing suggestions for policymakers to increase access to opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment at opioid treatment programs (OTPs). In summary, Pew offered the following recommendations:

- Establish more OTPs. States can eliminate legal obstacles that prevent OTPs from opening, and behavioral health agencies and Medicaid programs can adopt innovative OTP models that better meet individualized patient care needs.

- Facilitate access to methadone. Federal and state policymakers can allow patients to access medication as they await placement in an OTP, and grant OTPs more flexibility in dispensing methadone to more patients for longer periods of time.

- Expand Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement, and increase the number of participating OTPs. Congress can pass legislation that requires Medicaid programs to permanently cover all medications for OUD, and policymakers can incentivize OTPs to participate in both programs.

Separately, a data investigation published last week on the JAMA Network yielded findings that seemed to offer more support for these recommendations—particularly with regard to the importance of government reimbursement, an area of addiction care that typically doesn’t get a lot of attention. In the JAMA study, researchers found that from 2014 through 2018 the prevalence of medication use for OUD treatment increased among U.S. Medicaid enrollees across 11 states.

“Medicaid plays an incredibly important role in our health system, and the population it serves overlaps with those most likely to have opioid use disorder,” said study co-author Julie Donohue, Ph.D., chair of the University of Pittsburgh’s Department of Health Policy and Management in the Graduate School of Public Health. “But Medicaid is 50-plus separate programs that can’t easily share data. For the first time, we’ve pooled a large part of that data, enabling us to draw powerful conclusions that could better enable our country to address the opioid epidemic, which has only grown more intense during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

No Single Overdose Solution

Lawrence Weinstein, M.D., chief medical officer at American Addiction Centers, agrees that data, government intervention and regulation—including removing barriers to care—all are vitally important in bridging the current treatment gap. He’s also quick to point out that any singular effort to turn back the tide of rising overdose deaths and addiction complications won’t be enough.

“I think oversimplifying and pointing fingers at one area has been a mistake,” Weinstein says. “To address it, we’ll truly need a multipronged approach. And it’s not only services related to substance abuse. The complexity is augmented by the fact that there are comorbidities associated with substance abuse, short- and long-term. And the longer they use, the more comorbidities and more extensive sequelae from those comorbidities we see, both in numbers and outcomes. Particularly, it’s not only physical health, but behavioral health and mental health.”

Weinstein emphasizes the urgent need for expanding telehealth, sharing data across systems and spearheading research that supports clinical analytics and predictive modeling. He suggests a host of online services that will be engaged by and for people with addiction, including:

- A user application identifying updated local addiction services (Narcotics Anonymous meetings, for instance) that would be easily accessible via phone or tablet

- Simple and direct virtual patient-to-caregiver contact and an asynchronous approach to telehealth

- Continuous availability for providers to prescribe controlled substances (including buprenorphine) over the phone

- Breaking through state barriers and enhancing reciprocity to prevent services from being denied or delayed

“All these things we’ll need to look at in the future in order for us to raise the bar and really bring the substance use disorder and addiction field on par with our other areas of medicine that are rapidly progressing,” Weinstein says.

Top photo: Tim Mossholder; bottom photo: Nubelson Fernandes