Brian Cuban is a lot of things—former lawyer, author, public speaker, brother of billionaire Mark Cuban—but one label suits him best: sober

By Jason Langendorf

Brian Cuban, an attorney turned author and public speaker, struggled with multiple mood, substance use and eating disorders before entering treatment and recovery in his 40s. A Dallas resident since 1980, Brian is the younger brother of Mark Cuban, owner of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks.

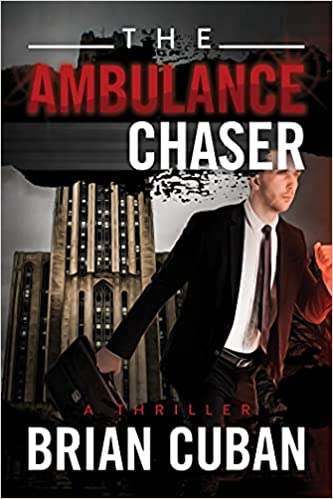

After giving up law as a profession more than a decade ago, Cuban, now 61, began writing. He has since penned three books: Shattered Image: My Triumph Over Body Dysmorphic Disorder, The Addicted Lawyer and a new thriller, The Ambulance Chaser. Cuban also speaks at law schools and law firms and in other settings, chronicling his personal experiences and connecting with others who may be at risk or need help.

TreatmentMagazine.com spoke to Cuban about his recovery journey and where he’s at now.

Q: You haven’t practiced law for some time now. Did you have to make a choice once your other endeavors started demanding more of your time?

A: I went to school for all the wrong reasons. During my time at University of Pittsburgh Law, I was an alcoholic, and I was also suffering from bulimia and exercise and eating disorders. I went to Penn State as an undergrad in criminal justice, and I decided to go to law school just so I would have another four years that I wouldn’t have to deal with my issues. Not a good reason to go.

“But, of course, what does a human have to do to survive? We have to eat, right? So I’d eat again, but I would restrict myself even more.”

—Brian Cuban, author and recovery advocate

Q: What ultimately compelled you to become so publicly vocal about some of these issues and start advocating for the causes?

A: I first went public with my eating disorders back around 2007, 2008. I received all these emails from guys struggling with eating disorders—my last name obviously has an impact. And I realized that I had the ability to give people hope for recovery, and then I went on to transition into doing that with substance use disorder as well.

Q: Bulimia and body dysmorphia are traditionally considered to be conditions that affect women and girls. How did that factor into your own experiences, and are you aware of other men and boys who deal with these disorders and face their own unique sets of issues?

A: Yes, it is stereotyped. It is stigmatized as a primarily female disorder, even though we know that up to 40% of all those with eating disorders are, in fact, male.

When I developed bulimia—this was as a freshman at Penn State in 1979, ’80—it was before even Karen Carpenter, the singer with The Carpenters, passed away from complications related to anorexia in 1983. [Carpenter’s death] brought these disorders into the pre-digital national spotlight, and it cemented the stereotype as a female disorder. So I was going through it at a time when no one was talking about it for guys or females—but certainly not males. I don’t want to get too triggering here for readers who may be in eating disorder recovery, but I had been bullied severely as a child and even physically assaulted over my weight, so I had tons of body-image issues going into Penn State. Every time I ate, there would be shame. If I gained a pound, it was one more step toward not ever being accepted.

I began to restrict my food intake. And that quickly transitioned into binging and purging. I didn’t think about it. I didn’t know what binging and purging was. There was no name for it. When I expelled the food that I ate, it was, ‘Okay, I’m not going to gain weight now.’ So there was no intellectual probing about what an eating disorder was, because I had no concept. It was just something I did. It gave me a sense of relief, normalcy—a sense that everything was going to be okay. But, of course, what does a human have to do to survive? We have to eat, right? So I’d eat again, but I would restrict myself even more.

Q: Eating disorders are thorny that way, sort of backwards from what we think of in terms of addiction. The substance isn’t taboo—it’s necessary for survival.

A: But there is a 50% correlation between eating disorders and substance use disorder. Of course, we know the way substance use disorder works. You can certainly get yourself in the mindset that you have to have the substance to survive, right? Especially with opioids, because you go into withdrawal. You truly believe you need to do it to survive.

Q: It seems to be a special wrinkle, though. Eating disorders are hard for many people to wrap their heads around, in part because food isn’t a “substance.”

A: There’s also a misunderstanding of what they are. It’s not uncommon for someone to go to their primary care physician, who is not trained in eating disorders, and that physician tells them they just need to eat more.

“And, look, I have a lot of privilege. I have financial privilege, skin color privilege. How many people have a billionaire brother who will send you to treatment, whether you have insurance or not, with a phone call? It would be disingenuous not to acknowledge that.”

—Brian Cuban

Q: You went into recovery for your eating disorders, substance use disorder and alcohol use disorder at the same time. At what point did you realize you had a real problem on your hands?

A: I mean, there’s this saying about cocaine: It’s fun until it’s not. As long as it’s fun, you overlook all the other stuff. And I’m binging and purging, drinking—and getting drunk makes it much easier to binge and purge. So in the summer of 2005, I had lost all my clients save for a few, and I was no longer able to practice law on any kind of level. Things got so bad with the cocaine and the alcohol, and Xanax was thrown in. Couple that with major depression, and I lost hope. I decided I would be doing my family a favor by ending my life by suicide. So I sent a disturbing email to a friend, who contacted my two brothers. My younger brother, Jeff, came first. I had cocaine, Xanax and a .45 automatic on my nightstand. Then my older brother, Mark, flew in from L.A., and they took me in for my first of two trips to a psychiatric facility. I’m literally kicking and screaming, while they’re trying to save my life. Even then, I just wanted them to get out of my life, leave me alone.

I refused to go to treatment. And, look, I have a lot of privilege. I have financial privilege, skin color privilege. How many people have a billionaire brother who will send you to treatment, whether you have insurance or not, with a phone call? It would be disingenuous not to acknowledge that. Substance use disorder doesn’t discriminate on an individual basis, but it does hit demographics differently—underserved demographics, people of color. But even with all this privilege, I refused to go to treatment. So, much to the chagrin of my brothers, they have to take me back home. They took my car keys, said to stay in the house for two weeks: “Don’t go out, we’ll get through this.” But that’s not how substance use disorder works. Some people do recover on their own, but that wasn’t me. I had severe substance use disorder, and my thought was, Hey, my drug dealer delivers. My guy makes house calls.

But looking back, that was the beginning of resilience. It all came to a head when I met someone, and she didn’t know anything about my issues. We began dating, and she moved in around 2006. I remember one of my party buddies saying, “Well, how’s that gonna work?” And I said, “This is gonna be my impetus to stop, because I really like her.” But that’s not how addiction works either. On Easter weekend 2007, she went away for the weekend to visit family, and I went out. The next thing I know, it’s two days later and she’s looking down at me, and there’s the cocaine on my dresser and the Xanax. She’s looking down at me and I’m looking up, and she’s probably trying to figure out if she’s in the right house. And I’m trying to think of how I can explain this Law and Order episode, this orgy of evidence that I might not be the person I represented myself to be. Which I wasn’t. I was no longer a lawyer anymore; I didn’t have any clients. Mark was taking care of me. And there’s that privilege again. I was just very fortunate to have brothers who loved me dearly and didn’t want to see me under a bridge.

Q: Another six years passed before Shattered Image, your first book, was published. When did you realize you were a writer, or decide that you wanted to become one?

A: It was a progression. I don’t think I ever had any bright-line moment where I said, “I’m a writer.” I still argue that I’m not. But we’re our own worst critics. I mean, I always sucked at math and excelled in English. That’s why I wound up in law school and didn’t go to med school.

Q: Do you see that as being a factor in mental health—young people feeling pressure to pursue work in high-profile professions?

A: It’s huge—the percentage of law students who end up with mental health issues because they feel trapped. They don’t want to do it in the first place. Maybe their parent was a first-generation lawyer. Maybe everyone in their family is a lawyer. They feel pressure, and they don’t want to be there. I mean, unhappy is unhappy, right? It can trigger issues if you don’t want to be there, if you’re unhappy—transitionally unhappy—because law school is tough. So now somebody who may have come into school with mental health issues already, they get worse. Or someone is triggered into drinking. So, there’s a whole spectrum of variables.

Q: Your first two books were essentially memoirs. Your new book, The Ambulance Chaser, is a novel. But the narrative seems to have a number of parallels to your own life. How much of it is autobiographical?

A: To give you the elevator pitch, the main character is accused of the murder of a high school classmate 30 years prior, and he becomes a fugitive in order to find the one person who can prove his innocence and save this abducted son. It takes place in Pittsburgh, which is where I’m from. And Jason struggles with cocaine and alcohol. He has his inner struggle, and he has to come to terms with that in order to save his own life and save his son.

I didn’t want the character to be a full trope of the alcoholic lawyer. There are moments where you say, “Okay, this guy has an issue,” but it isn’t full-out over the top. He has a journey through addiction that is much more subtle than a Leaving Las Vegas or, you know, Paul Newman’s Frank Galvin in The Verdict. That’s intentional, because the narrative is usually more subtle in real life.

Q: Your blog is very candid. You mention in one that all your birthday celebrations had been in Las Vegas or Miami. Are you ever triggered by visiting places or with people from your old life?

A: The people I partied with—I still know them, but it’s not the same. It’s not the deep connection you have with people who would support you if you had never reached out. The people who were my friends before all this are the people who are my friends now. So I don’t really get into those old situations. When I go back to Miami and Las Vegas, are there triggers? Not really, not anymore. I’m in a different place in my life now. I joke that sometimes I walk into a bathroom and I think, Is this a good cocaine bathroom or a bad cocaine bathroom?

“I don’t joke about anyone else’s journey, right? It’s my journey to joke about.”

—Brian Cuban

Q: Some people may be horrified to hear that stuff. Is it liberating or healthy for you to sort of joke about it?

A: I don’t joke about anyone else’s journey, right? It’s my journey to joke about. I mean, in 2006 I was trading championship Mavericks tickets to my cocaine dealer, and then I flushed all the cocaine down the toilet when I got all paranoid.

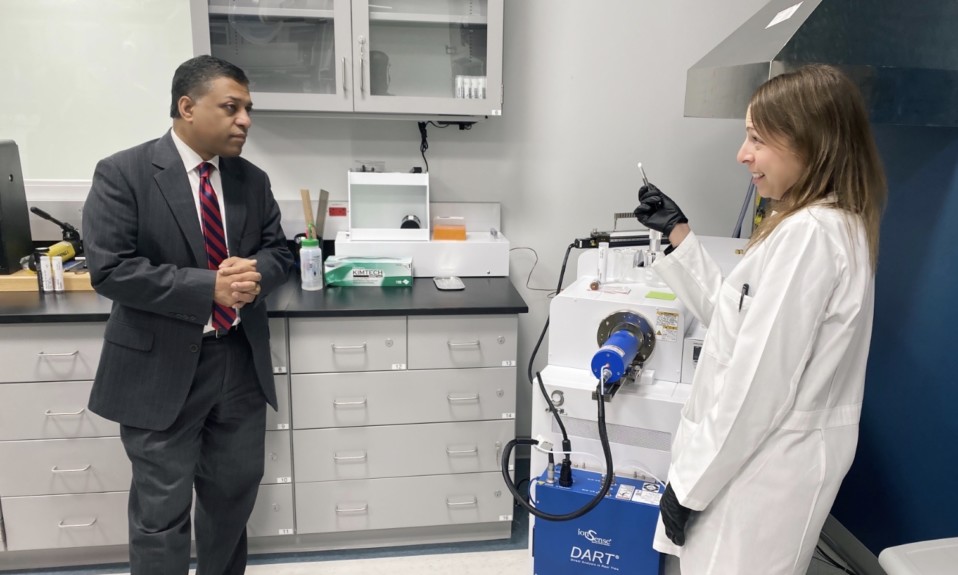

Q: Your brother, Mark, is best known as the Mavericks’ owner, but he strikes a balance between entrepreneurship and philanthropy. His latest project is an online pharmacy for affordable generics, including treatments for mental health and smoking cessation. Is that coincidental?

A: The moment I knew he was in this deal, I texted him about Naloxone. He’s aware of it, and I made sure I texted him about how that fits into the business plan. Like anyone else, I would love to see Naloxone more accessible, cheap.

Our father was a working-class guy. He was always willing to help people. He and his brother, Marty, operated what’s known as a trim shop, putting on convertible tops and reupholstering seats in cars and couches and stuff. A middle-class guy in Pittsburgh for over 40 years. He was a wonderful father, and he instilled those values in us. You know, always be kind. We’re Jewish, and there’s a Jewish saying: tikkun olam. “Change the world with acts of kindness.”

Bottom photo: Shutterstock