As the national suicide hotline transitions to 988 in July, federal, state and local agencies are scrambling to build out infrastructure—and find folks to handle a massive increase in calls

By Mark Mravic

There’s no denying the numbers: America is in the midst of a mental health and suicide crisis. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nearly 46,000 Americans took their own lives in 2020, making suicide the 12th-leading cause of death in the U.S., and there were an estimated 1.2 million suicide attempts. Mental Health America’s most recent report found that nearly 20% of adults experienced a mental health illness in 2019, amounting to some 50 million people. But less than half of U.S. adults with mental illness receive treatment.

The issues are particularly acute among young people. In 2019, the CDC notes, 36.7% of high school students reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, an increase of 40% over the previous decade; and 18.8% of high schoolers reported seriously considering suicide. The COVID-19 pandemic has only amplified the problem. In early 2021, emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts were 51% higher for adolescent girls and 4% higher for adolescent boys than for the similar period in 2019.

Overall, according to Vibrant Emotional Health, a nonprofit that administers the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, more Americans die from mental health crises and substance use in a single year than have died in combat in every war combined since World War II.

But suicide is preventable. According to Vibrant, for every person who dies by suicide, there are 316 who seriously consider it but do not follow through. And for those who do attempt suicide, 90% go on to live out their lives.

Amid this landscape, prevention efforts are about to expand significantly, with the transition of the Suicide Prevention Lifeline to the three-digit 988 number this summer. The change comes with a massive infusion of resources to support the projected increase in call volume—and with challenges in building out the infrastructure and the staffing to handle the heavier load.

A Call for Change

In October 2020, Congress passed the National Suicide Hotline Act, designating 988 as the new nationwide number for suicide prevention and mental health crises, beginning on July 16, 2022. Modeled after 911, the new number takes over from the 10-digit 1-800-273-TALK (8255), and is intended to be easier to remember and to connect with. The service is meant to expand and strengthen America’s mental health safety net, with the goal of providing 24/7 behavioral health care to anyone in crisis, anywhere at anytime. A key component of the reimagined service, advocates say, is to move mental health calls from 911—where responders may not have adequate training, and where people in crisis too often wind up in traumatic engagements with law enforcement—to compassionate mental health professionals.

The transition has been backed by unprecedented resources for a service that faced years of funding shortages, coverage gaps, access difficulties and stigma. Last December, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) announced $282 million in funding for the Lifeline—a whopping 40-fold increase over 2020 spending levels. “998 has galvanized a field which has struggled in the past with fragmentation and gaps,” John Palmieri, MD, MHA, acting director of SAMHSA’s 988 and Behavioral Health Crisis Team, told reporters on a call last month. “Not only are we all at the table, [but] there’s genuine excitement for the opportunity of transformative change, and addressing mental health, suicide and substance use needs [is] a leading part of the federal conversation.”

Added John Draper, PhD, executive director of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and executive vice president for national networks at Vibrant: “We are building on a network that has proven what it can do. But we do expect a lot more people will be accessing the services.”

Funding 988

And for that, money is needed. The $282 million from SAMHSA is going through two funding channels, the impact of which, Palmieri said, “is just beginning to materialize”:

- $105 million to states to fortify their local centers. SAMHSA has been working directly with states, territories and tribal nations to determine how much will be allocated to each of the more than 200 call centers across the country. The money is earmarked for expanding capacity, training workers and volunteers, providing proper follow-up to calls and—crucially—paying staff.

- $177 million to Vibrant, which has been overseeing the Lifeline since 2005. The money is going toward strengthening the national service, including expanding technological capabilities, building out the Spanish-language network, increasing services in marginalized communities, and providing backup to cover local staffing and capacity shortfalls during the transition.

That last element is the top priority for July. “As state and local readiness is going to vary across our network, our most intensive focus right now is supporting the safety net behind the frontlines,” Draper said. The goal, he notes, is to “assure that by July, we’re able to plug those gaps where crisis services are insufficient to respond locally—that wherever there are holes or gaps where those calls or chats or texts cannot be answered locally, they will be answered by someone.”

A Huge Projected Expansion in Call Volume

The current system, as noted, suffers from coverage gaps depending not just on locale but on the way someone reaches out for help. In 2020, according to SAMHSA’s appropriations report, phone calls to the Lifeline made up a little more than half of all encounters and had an 85% answer rate. Chats comprised a little less than half of all contacts in 2020, but their answer rate was a troubling 30%. (Texting, introduced in mid-2020, had a 56% answer rate, but encounters were low given its newness.) Clearly there’s need for improvement—especially as demand for the service is expected to grow significantly after the 988 transition.

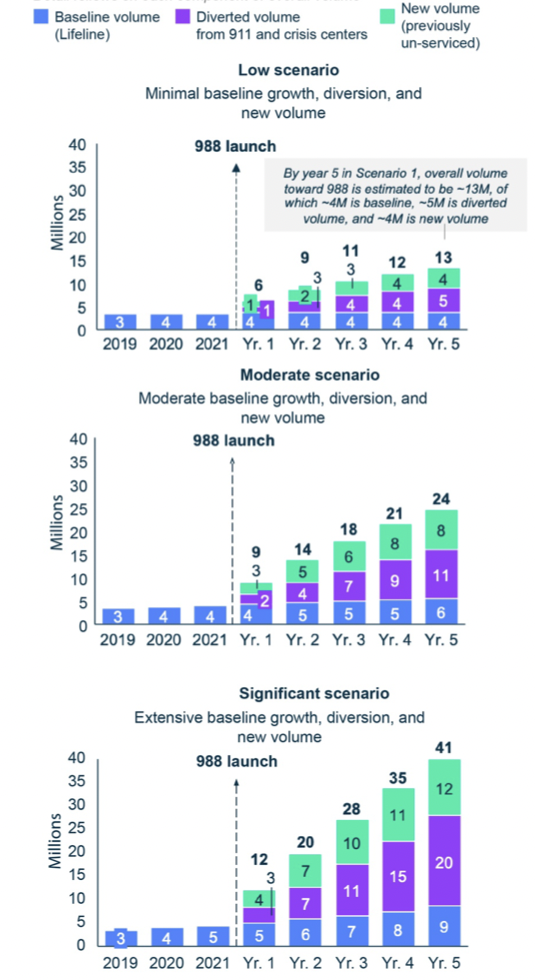

Just how much? In 2020, the 10-digit Lifeline received 3.3 million calls, chats and texts. Going by past figures, SAMHSA estimates that baseline call volume will increase 14% a year. But that’s only one source of the anticipated rise in volume after the new number goes live—and not the largest source. As noted earlier, many contacts that now go to 911 or other mental health crisis lines will be diverted to 988. Additionally, the Lifeline is expected to see large numbers of new users—people who otherwise wouldn’t be reaching out but are doing so because 988 is easier to remember. Taking those factors into account, SAMHSA’s mid-range estimate is that in the first 12 months of 988—from launch through July 2023—the volume of encounters will more than double, to 7.6 million.

Future estimates are even more imposing: For Year 5 of the program, projections range from 13 million encounters on the low end to 41 million in the highest-growth scenario. Draper calls it “the largest mental health crisis program that we’ve ever established.”

Who’s Manning the Phones?

Those increases would be formidable in normal times. But given that the behavioral health field is already facing a labor crunch—some say crisis—meeting such demand will be a daunting prospect from a staffing perspective. “We are painfully aware of the many workforce challenges facing crisis providers,” Palmieri said. He spelled out a number of initiatives to increase visibility and awareness of options for current and potential workers.

- A recently launched jobs and volunteer landing page, connecting users to opportunities across the network’s more than 200 local call centers.

- Emphasis on diversity of background. “This is not a situation where we’re only looking for licensed mental health professionals,” Palmieri said. “There’s tremendous value in bachelor’s-level individuals, paraprofessionals, peer-support workers—they all bring tremendous value to the workforce.”

- Innovative workforce development. Palmieri points to other levers that can be pulled at the federal level to create pipelines into crisis care work, including building on relationships with education partners and establishing internships at service organizations such as AmeriCorps.

- Enhanced flexibility. “We’re amplifying the flexibility that exists when there are remote options,” Palmieri said, “understanding that a lot of people in the current environment want to be able to pursue remote work options.”

- Retention. In the era of the Great Resignation, keeping staffers can be as difficult as finding them. “This can be challenging work, obviously,” Palmieri said, “and so [we need to make] sure that we have [programs] in place to support resilience, decrease burnout and make sure that individuals who are providing life-saving crisis care have the support they need for themselves.”

Vibrant’s Draper notes that there’s already staffing in place that’s ripe for expansion. “Many crisis centers have operated in the community with volunteers for many years,” he says, “and so already there’s a workforce ready to be paid and do full-time work.” With the new influx of funding, Draper says, “We can really start to build career pathways for people in crisis care that we’ve never had before, especially as we build out the crisis care continuum.” Given the current and projected demands, he adds, “This is a great time to be a crisis counselor.”

Easing the Transition

To smooth the changeover, rollout leaders are encouraging states to moderate their public education efforts up to the July date. “Until functionality is fully accessible,” said Palmieri, “SAMHSA recommends that widescale promotion of 988 as an available service happen after the July 16 transition.” The current 10-digit number will continue to work after the rollout—and, in fact, will work in perpetuity, so that people who have it written down or who see an older sign will still connect to the crisis line. (Draper says an even older national number, 1-800-SUICIDE, still receives calls despite having been officially retired since 2005.)

After mid-July, progress of the rollout, including public education, will depend on where each state or locality stands in building out its infrastructure. “Once the transition takes place,” Palmieri said, “local promotion strategies should consider service design and availability and be tailored to those local circumstances.”

The Sustainability Question

Of course, a sufficiently built-out service—which, advocates say, will take well beyond July 16 to achieve—has to be sustained long-term. A report by SAMHSA notes, “As awareness of 988 increases, funding for nationalized services will need to remain sufficient to provide high-quality services rapidly for individuals in a mental health or suicidal emergency.”

Palmieri pointed to potential continuing funding streams beyond this year’s $282 million infusion from SAMHSA. The development of those additional revenue sources will be key to ensuring the sustainability of 988—especially if there is an administration or policy change in Washington. Sources could include other federal grant programs such as Mental Health Block Grants; Medicaid and other payers; states’ general funds; and cellphone fees imposed to support 988, which the 2020 act specifically authorized. Several states have already enacted or are considering levying such fees, with some pushback from telecoms.

Congressman Seth Moulton (D-Mass.), who wrote the federal 988 legislation, takes a pragmatic approach to the issues surrounding the rollout. “I can’t say that I’m 100% satisfied with the progress all the states are making towards meeting this deadline and truly being ready to go in July,” he told WGBH news in April. “But we can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

As for the workforce issue, which may be the greatest challenge of all, Draper is realistic. “Let’s be clear,” he said. “We’re not going to be [able to] make sure that every center in the country is going to have a direct pipeline to get all the staff they need by July. This is going to be a long-term building process.”

Until July 2022, anyone in mental health crisis or emotional distress should continue to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

Top photo: Gilles Lambert