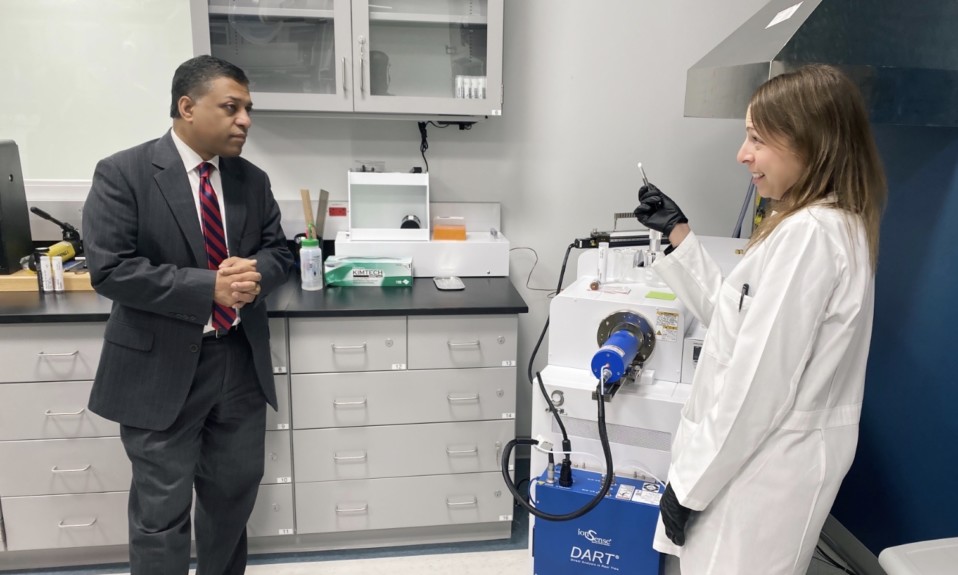

Led by surgeon Luke Elms and opioid outreach coordinator Jaime Bridges, the Florida-based healthcare provider is focused on a more individualized treatment of pain

By Jenny Diedrich

For many with opioid use disorder (OUD), addiction begins in the hospital. Thus, a new program implemented by Florida-based Orlando Health aims to reduce or eliminate opioids after surgery by using safer drugs and techniques that still can offer powerful pain relief.

The opioid avoidance program is part of a comprehensive approach by Orlando Health to combat the opioid epidemic. The program includes an opioid coordinator who’s trained to recognize people struggling with or at risk for OUD and provides resources to ensure patients are supported in the hospital and after they leave.

Luke Elms, MD, a surgeon at Orlando Health Dr. P. Phillips Hospital in Orlando, put the protocol in place. “The goal is to provide compassionate pain control in the safest way possible,” he says. “If our solution to the problem with opioids is to just pull opioids away and leave people in pain, then that’s not a good solution. It runs against the tenets we have as medical professionals. There is opportunity to achieve that goal without exposing people to as many or any opioids.”

TreatmentMagazine.com recently spoke with Elms and Jaime Bridges, LCSW, opioid outreach coordinator at Orlando Health, about the opioid-focused pain management that has historically been practiced in the U.S. and the potential of their new protocol.

Q: Orlando Health recently did a survey around Americans’ perception of the need for opioids after surgery. What were the findings?

Elms: According to the survey, up to 78% of patients believe opioids are necessary after surgery, and two-thirds expected to receive a prescription for opioids. That was not necessarily [a surprise]. The opioid-centric pain management model has been prevalent for so long.

Sixty-five percent of people were more worried about their pain control in the post-surgical timeframe than they were about the risk of addiction from opioids. Obviously, that’s a valid concern. Surgery and the interventions we do as physicians cause a significant amount of pain, and it is something we have to take into account as we move into more non-opioid treatments.

The encouraging part was that 68% were willing to try non-opioids if they provided good pain control. Those numbers have been very evident in my own practice, where I treat general surgery patients. The majority of people really just want to be sure their experience is as smooth as possible and that their pain is managed in a way that allows them to recover.

Q: How has pain typically been managed in the U.S. following surgery?

Elms: When we talk about the pain management model that has been utilized in the U.S. over the past few decades, it’s been very opioid-centric. If we do surgery on someone, there is upwards of a 9% chance they are refilling their opioids 120 days after surgery. We know that what we do causes pain and that exposure to opioids can cause dependency in some populations.

There has been untapped potential in use of non-opioid medications to gain better pain control with minimization of exposure to opioids. In the United States, we have a chance to start to shift the way we view pain control to less of an opioid-first pain control model. There may be opportunities where patients who historically have been exposed to opioids may be able to gain adequate pain control with non-opioid methods. Then they don’t have that risk at all.

The aspect of the anxiety of surgery and mental health is important. It’s amazing how much better pain control people have when they know what to expect and they know we’re not going to leave them by themselves.”

—Luke Elms, Orlando Health

Bridges: Most of those patients who already suffer from opioid use disorder are convinced that the only way to control their pain is with opiates. We may still use opioids but will start to introduce some of those other ideas. There are amazing combinations of medications that may even be better in controlling pain. If we try to not throw one thing at pain, we might have a better chance of preventing the situations we’re currently seeing.

Q: What is the opioid avoidance protocol you’ve implemented?

Elms: The protocol is to use non-opiate medications. Many of them are available over the counter, such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen. When used in combination, they can provide very good pain control because they work on different pathways. That doesn’t mean everyone can make it through with just those. Many times we’ve found that it is enough, and people are able to get through their recoveries that previously have used opioids.

The real key has been to make sure the patient education component is there. We have very upfront, frank conversations with people that they will have pain. The aspect of the anxiety of surgery and mental health is important. It’s amazing how much better pain control people have when they know what to expect and they know we’re not going to leave them by themselves.

Bridges: I address patients who may already have OUD and overdoses that come into our emergency room. My role is basically working with the patients and meeting them where they are to see if they’re ready to make changes.

On the education side, it’s educating our staff on how to treat OUD. It is an addiction, however. One of the best ways to treat it is with medication-assisted treatment. Surrounding those medications, there are a lot of ins and outs about how they can be used and prescribed. I also make sure patients are connected with treatment centers after they leave the hospital.

Q: Are there any misconceptions around this protocol?

Elms: There’s a fear among patients who have chronic pain or palliative care issues that we’re trying to say opioids are unnecessary. That’s not what we’re trying to say. We’re trying to address patients as individuals and understand that historically our pain control model in the U.S. has been very one-size-fits-all. If you address the individual, many times we can provide compassionate pain control in a manner that eliminates or limits exposure to opioids.

Opiates have a purpose, and we realize some people may have to be on opioids for the rest of their lives. They are a great tool, but there are so many other tools in our belt. Why not go to other tools first?”

—Jaime Bridges, Orlando Health

Bridges: As someone in recovery from opiates and an advocate for people getting into recovery, I’ve learned a very valuable lesson. Opiates have a purpose, and we realize some people may have to be on opioids for the rest of their lives. They are a great tool, but there are so many other tools in our belt. Why not go to other tools first? It’s important for us to make sure we have conversations with our patients and understand their individual goals.

Q: What other medications and interventions are there that can help control pain?

Elms: There are many other interventions that can really add up. One is meditation. People who have severe pain say that’s not going to be enough, but our goal is to get you better pain control than you have now. Even if [a patient] does need opioids, we can give better pain control if we also utilize other methods. We have patients whose main complaint is they’re having muscle spasms at the site of their incision. A muscle relaxer works very well with that type of pain. When you add in more of a targeted fashion with the backup of opioids, the way you approach pain control really starts to change.

Bridges: I was addicted to pain pills for about 10 years and have been in recovery for 10 years. I had a lot of things within myself that I wasn’t happy with. Opiates can make someone feel better physically and even psychologically. One thing we do in the hospital is assess where they are with their mental health. If someone is already vulnerable and we’re giving them medication that can eliminate psychological pain, they may be more likely to abuse that medication.

I was injured in a fire and was very much in fear of taking opiates. The doctor said, “We can’t treat you without opiates.” The difference was I was aware. I was able to take the [opioids] as needed and as prescribed and then get rid of that medication. We want to make sure that at the hospital we are addressing all sides of the patient—not just physically but also the mental health side.

Q: Can you share one of your success stories?

Elms: One of the success stories I like best is a gentleman who was recovering from severe perforating appendicitis and had open surgery. In recovery, he was having horrible pain. We were giving multi-modal therapy and large doses of opioids. At about day two or three in the hospital, I had deep conversations with him. He said, “Honestly, I think it’s my anxiety. I’m so scared I’m going to be in pain, and it’s making it a lot worse.”

We consulted with the psychiatric team, and they modified some medications to get his anxiety under control. He went home taking opioids at the lowest dose a couple times a day for about three days. Otherwise, he was just taking non-opioid medications. That patient was one of my biggest feelings of success in this whole journey. Historically, that patient would have been discharged with large doses and quantities of opioids. By figuring out exactly what was causing [his pain] and addressing those things, we were able to significantly decrease his opioid exposure long-term. The experience of pain is much more than just nerves firing. It’s a full-body, whole-person experience.

Top photo: Lilartsy; bottom photo: Hush Naidoo Jade Photography