With the hiring of Andrew Williams, the foundation is demonstrating that creating an atmosphere where everyone has access to treatment is more than just a catchphrase

By Jason Langendorf

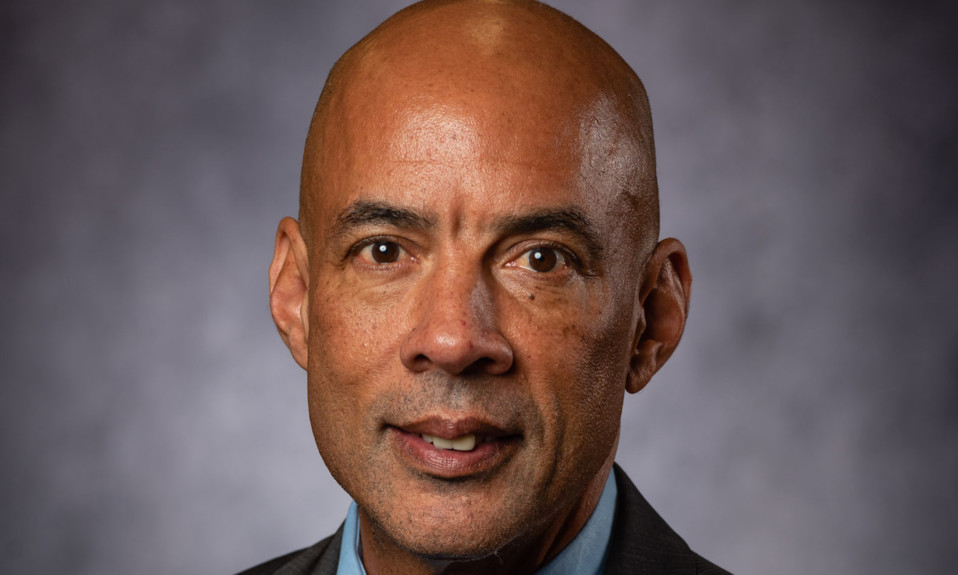

When the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation named Andrew Williams its first-ever director of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) last week, it described the position as “a new leadership role focused on increasing inclusion and removing barriers.”

Williams arrives at Hazelden from the University of Minnesota Rochester, where he served as assistant vice chancellor for student success, engagement and equity. He will start his new job at Hazelden on June 7.

As part of our treatment leadership series, TreatmentMagazine.com spoke to Williams about the nature of his new role, noting the significance of the date of our interview (conducted on the one-year anniversary of the murder of George Floyd) and emphasizing the importance of an intersectional approach that expands DEI beyond the boundaries of race.

Q: Back in March, when then-incoming Hazelden CEO Dr. Joseph Lee spoke with TreatmentMagazine.com, he noted his deep commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion. During your hiring process, what were some prominent themes or topics of discussion?

A: There already is a lot of good momentum around advancing diversity, equity and inclusion at Hazelden. Although mine is a new position, there’s been a DEI committee, and it’s been doing really solid, important work. I think they offer the organization a strong infrastructure and foundation to advance that work. They’ve already developed an emergent action plan that’s in place and evolving, which I’ll get to help shape and direct. But I’m not arriving in a vacuum. There’s lots of good momentum going on here, a lot of intentionality and attentiveness to the issues within the organization.

The highlight—one that resonated with me and really affirmed that this was an opportunity that was going to be really meaningful and nourishing for me—was that no matter how we approach this work, we will do it with some bold humility, with empathy, with love and grace and compassion.”—Andrew Williams

As I drill down a little bit deeper, among the themes that stood out was access. From Dr. Lee, from professionals in marketing and communications, from those who are engaged in direct service to clients, the message was that we really need to expand access to historically marginalized or minoritized populations. I think Dr. Lee often speaks of broadening our banner externally, and that’s definitely one of the themes—Hazelden deepening its commitment, wanting to expand engagement with those communities that have been historically underrepresented.

I think another important piece of this work, and one of the themes I heard, was around internal change—in particular, a commitment to ensure that the professional staff at Hazelden Betty Ford is more reflective of the diversity of our national demographic as well. We can continue to do better, bringing in diverse individuals, diverse voices and perspectives into the organization. That’s probably going to have to happen through recruitment, developing pipelines from different colleges, universities and graduate programs. But it’s also important—and this is, I think, another major theme I heard from Dr. Lee—to create internal pathways within the organization. So his appointment to the CEO position and my arrival in this DEI position kind of places down a signpost that says, “Hey, there are pathways within the organization to advance towards senior leadership and other positions.”

The highlight—one that resonated with me and really affirmed that this was an opportunity that was going to be really meaningful and nourishing for me—was that no matter how we approach this work, we will do it with some bold humility, with empathy, with love and grace and compassion. We need to bring a developmental perspective to this. We’re all products of our socialization. These are all very complex issues.

Q: Whether it’s a caregiver or an administrator, how important is that element of diversity in connecting with the patient population. Beyond issues of equity, how does it affect addiction treatment outcomes?

A: I think the research is fairly clear that when we have more professionals of color—when we have more psychologists, psychiatrists, medical professionals of color—we see better outcomes, whether it be in this area of addiction services or in other areas of healthcare more broadly defined. The research indicates that as we diversify, especially in those providing direct services, that we’re likely to have better outcomes as our clients are more likely to be more trusting. It’s going to be easier to establish rapport, and there’s some common cultural ground.

I think the other piece, which is very connected to the theme of expanding access, is actually being able to engage others through partnerships with different community organizations, through our marketing. Ultimately, as someone who is a person of color, you look at organizations, and you kind of get a read: Do they have diversity, not just at the bottom levels of the organization, but also at the top? Do they have people of color? Do they have women and LGBTQ people in mid-level positions?

If we want to expand access, clearly some of that’s about identifying financial, cultural and socioeconomic barriers to our services. We want more people from historically underrepresented backgrounds to come into the organization. I think we need to reflect the diversity that [patients] see in their own communities. Another way to say it is that we are a symbol of our commitment to diversity and equity through our own demographics.

Q: How has your personal background influenced your professional approach?

A: Well, I identify as an African American male, in traditional terms—a cisgender male. I grew up in Indianapolis, in a largely African American, working-class community, which shared a border with multiple Jewish communities. So part of my interest and commitment to these issues is really grounded in my lived experience—moving across diverse African American communities in terms of socioeconomic status, but also moving in and out of the Black and Jewish communities. I’ve been crossing cultural boundaries for much of my life, which I even shared in my cover letter. I was raised by folks who were part of the Great Migration to the north, who escaped racial terrorism. My first soccer coach was my neighbor, a Holocaust survivor. Nowadays tattoos are all the rage, but the first tattoos I saw as a young kid were the serial numbers tattooed on the arms of my Jewish neighbors.

On one trip in particular, [my grandfather] took me on a walk. We walked down a long, dusty road in this kind of rural area in Pulaski [in Tennessee], and he took me to a tree and pointed out to me that it was here that his father, who would have been my great-grandfather, was lynched by the Ku Klux Klan.”—Andrew Williams

My mother gave birth to me when she was 17, and so my grandparents played a big role in raising me— including my grandfather, born around 1915, who was from Pulaski, Tenn. Pulaski is the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan. So every Labor Day, when I was a child, my grandfather would take me down to the farm that he grew up on to meet his mother, my great-grandmother. On one trip in particular, he took me on a walk. We walked down a long, dusty road in this kind of rural area in Pulaski, and he took me to a tree and pointed out to me that it was here that his father, who would have been my great-grandfather, was lynched by the Ku Klux Klan.

My grandfather was rather stoic and not a very demonstrably emotional person, but you could see the pain and hurt in his face as he described what it meant to lose his father to lynching. That experience, as you can imagine, really stuck with me as a kid. Combined with being close to the people who were factory workers and auto workers, working in electronics factories and being close to the Jewish community, this really fueled my interest in cultural diversity and these issues around systemic racism and the dangers of ethnic hatred—the ways it can lead to immediate and longer-term intergenerational trauma. It was those lived experiences that led me to go on to graduate school at the University of Michigan to study cultural anthropology to learn more about African American history, culture and politics, with race and racism at the center of my research and teaching as a traditional academic.

As an African American man, I grew up deeply embedded in a traditional Black community filled with Black laughter and love, and Black religion and music, and Black laughter and dance—all of that. But like many of us, I was not necessarily highly culturally aware. I was in it without having conscious awareness of it, in some ways, until I started bumping into racism in the school system. And then as I became more culturally aware, of course, I became more politically conscious as well.

As my own identity and thinking and understanding of the complexity of these issues has evolved, it’s always that reminder for me that we’ve got to take this developmental approach. None of us are born racist, sexist, homophobic, classist or ableist, right? These are all ways of being and thinking and engaging diversity that we learn. And because we’re always products of our socialization, we can’t move into the blame and shaming game.

That’s why I’m really attracted to Dr. Lee’s kind of orientation—that we have to bring humility, grace, empathy to this work. Having been embedded in diverse communities, having worked in academic institutions, I think we really want to understand the complexities of systems of oppression. And if we want people to feel seen and heard—if we want to understand the complexity of their identities—we have to bring that sort of intersectional lens and more expansive understanding of diversity.

Q: When you were hired, you said you hope to “intelligently complicate policy.” It’s a fascinating phrase. What does it mean to you?

A: That reference really draws from a quote from Wendell Berry, who was sharing some reflections on leadership. He talked about there being two key components of leadership, that there’s two muses. One is that muse of inspiration, who through their vision, through their words, through their own actions, their own ethical ambitions, inspire others to advance the mission of that organization or the values of the society. But there’s also another muse that’s just as important: the muse of realization. That is the leader who’s always asking more probing questions, who’s encouraging everyone they’re working with to pause a minute, to slow down to consider the full complexity of the issue, the policy, the practice at hand. One who is always willing to say that things might be more complicated than they appear.

To “intelligently complicate” our decisions is always asking the important critical questions. But I think more specific to my role as director of DEI, what that really means, in a more precise way, is that I want to be someone who’s always making sure that we’re taking equity into account as we’re making policy and practice decisions. Equity needs to be that complicating factor. Always asking, “Who will this policy, this practice, disadvantage or advantage? Will it further disadvantage minoritized groups? Who might that policy or practice further advantage?” It’s about asking questions that help us become more equity-minded and what I would call culturally attentive. “Who’s at the table, and who’s not at the table?” And maybe “Who else do we need here?”

And also raising questions around what will be the measure of our success. To raise intelligent questions means really grappling with the complexity of the data. Are we asking all the right questions of our data? Are we just aggregating our data? Beyond just people of color, beyond women, beyond certain cultural groups, are we getting the specific data that we need to fully understand where our victories are and where we still have some room to grow and improve in terms of access, representation, inclusion within the organization?

Q: Can you point to concrete DEI initiatives at Hazelden or across the field that you’re confident will deliver demonstrable change in the near future?

A: I like to be very honest: I still have a tremendous amount to learn about the field of addiction and recovery. And so I’m not able to speak with the kind of expertise or mastery that I hope to have down the road. But of course I certainly have a general understanding of what the big health equity issues are that need to be addressed, and I can say a little bit more about that.

[W]e’ll only be successful in advancing racial equity to the extent that we can be as committed, intelligent, sophisticated and driven in our approach [to] other forms of bias and other potential barriers within the organization, [such as] issues of gender, class and ability.”—Andrew Williams

I bring a very expansive intersectional approach to this work, thinking about diversity expansively—that it’s not just about advancing racial equity. That’s an important and key component, and we need in many ways to prioritize that because of the moment we’re in. But we’ll only be successful in advancing racial equity to the extent that we can be as committed, intelligent, sophisticated and driven in our approach [to] other forms of bias and other potential barriers within the organization, [such as] issues of gender, class and ability. That’s one thing I would emphasize, because I’ve been through some interviews and other things recently where, despite my emphasis on that, what gets heard is just the race piece.

In some ways I’m [traditionally focused on race], based upon my academic training and the traditions of W.E.B. DuBois and Paul Robeson. But I’m certainly bringing a more intersectional and expansive orientation toward this work. I think that’s what makes the most intellectual sense. It’s the most sophisticated approach, and I think the evidence suggests it’s going to be the most effective orientation in terms of positive outcomes.

Second photo from top: Francisco Venancio; third photo from top: Scott Graham