TreatmentMagazine.com turned to Linda Richter, Ph.D., from Center on Addiction to lay out the hard science relating to substance abuse

By William Wagner

Addiction: a disease or a character flaw? It seems this question has yet to be fully settled, but as the evidence continues to mount, more and more people are coming down on the “disease” side.

Specifically, the brain disease model of addiction mines the medical realm to solve the riddles of substance abuse. According to the model, addiction is rooted in a toxic mix of biological, environmental and behavioral elements, just as with diabetes or any other chronic illness. And the cure doesn’t rely upon being “strong” or “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.” It can be traced to hard science and its ability to deliver breakthroughs in medications and therapies.

Q: Do you feel there is still a societal belief that addiction is a character flaw. If so, why do you think this belief persists? What needs to happen to change it?

A: The view that addiction is a character flaw is still pervasive in our society, not only among the public but also among policymakers and health professionals. However, there has been a recent and significant shift toward seeing and addressing addiction as a disease and a public health issue rather than simply as a moral failing or a criminal justice problem. This shift can be attributed to a large and accumulating body of scientific research that demonstrates how addictive substances affect the brain and body. While scientific understanding of addiction as a disease and its impact on the brain has grown dramatically over the past few decades, there is still limited awareness and understanding of this research among the public.

A deeply entrenched stigma surrounding addiction and its treatment continues to permeate all levels of society. This affects how people view individuals with addiction, how people with addiction view themselves and how they are treated by health professionals, law enforcement, employers and social services. Because addiction historically has been seen as a moral failing, it mostly has been addressed through the criminal justice system and through a treatment system segregated from mainstream health care that is not held to the same quality standards as the treatment of other health conditions.

To eliminate this stigma and its far-reaching and disastrous consequences, the public, as well as healthcare providers and policymakers, need to be better educated about the causes, nature and consequences of addiction and about how to most effectively prevent and treat it. Furthermore, policies that segregate addiction treatment from general healthcare and that put onerous restrictions on access to needed care must be modified so that individuals with addiction receive quality and effective treatment.

Q: How would you define the brain disease model of addiction?

A: The brain disease model of addiction sees addiction as largely a biological condition, and draws on advances in genetics and brain research to understand and describe how addiction takes hold and affects the brain and body. This model of addiction was a vital reconceptualization of addiction, which historically has been seen as resulting from a moral or behavioral failing, as it allows for the relocation of treatment and prevention efforts from primarily the legal domain into the medical domain.

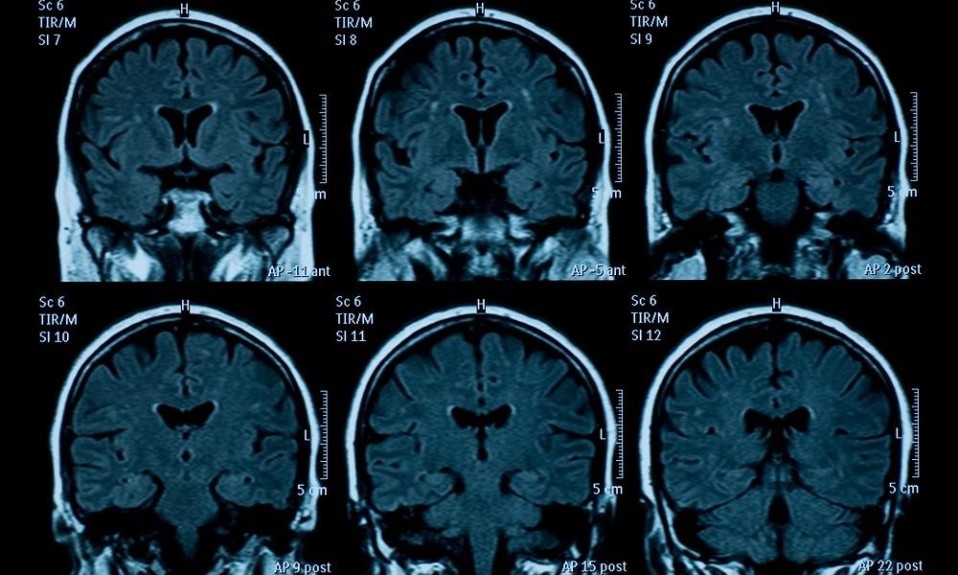

It presents addiction as a medical condition that involves changes to the structure and function of the areas of the brain involved in reward, stress, memory, decision-making and self-control. Changes in the brain caused by substance use can explain the compulsive nature of use that is characteristic of addiction, and those changes can be targeted with appropriate treatment. This perspective does not preclude the role of social and environmental factors in the development and perpetuation of the disease. Like many other illnesses, especially those that can be chronic, addiction is caused and sustained by a combination of environmental, biological and behavioral factors.

Q: How does substance use change the brain?

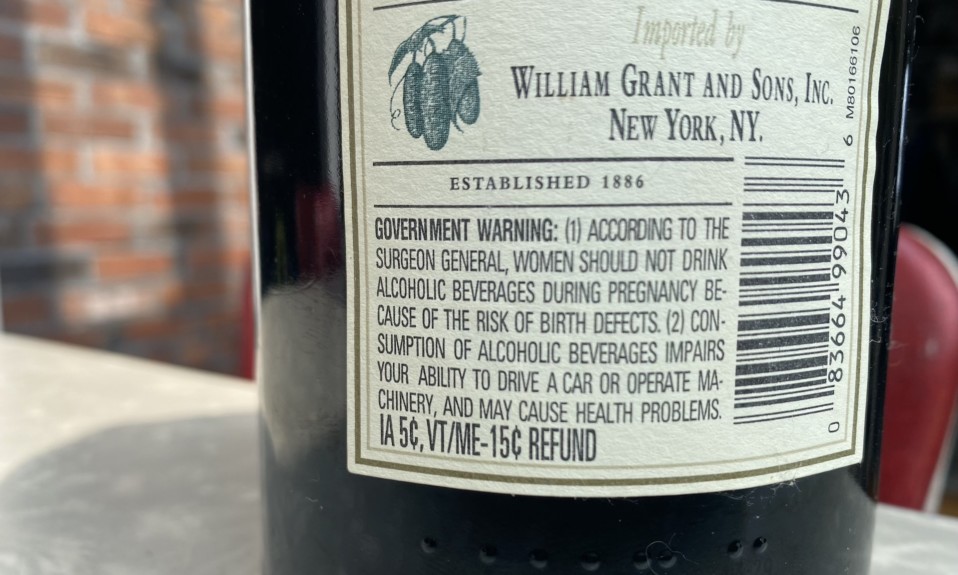

A: Addictive substances cause the brain to release high levels of chemicals associated with pleasure and reward, which reinforce continued and repeated use of the substance. Over time, continued release of these chemicals, known as neurotransmitters, produces changes in the regions of the brain involved in regulating pleasure, motivation, memory and other important cognitive and emotional functions. Typically, the brain strives to balance out the effects of the substance and return to a normal state by reducing its response to the substance.

This makes the person feel the need to use increasing amounts of the substance to experience those initial positive effects. Still, the positive effects dull over time, while the extensive negative effects of substance use on the brain, body and one’s life functioning accrue. These changes result in a need to use the substance simply to feel normal, intense cravings for the substance and/or continued use despite harmful or dangerous consequences. The changes in the brain can remain for a long time, even after a person stops using, which can make those with addiction vulnerable to physical and environmental triggers that increase the risk of relapse.

Q: Why are some people more predisposed to addiction than others?

A: As with other diseases and health conditions, several factors can influence a person’s predisposition to addiction. Early use of substances is one of the strongest predictors of addiction; more than nine out of 10 people with substance use disorders began using before age 18. Other important determinants of substance use and, ultimately, addiction are a family history of substance use or addiction, a genetic predisposition for addiction, a mental health problem, the experience of trauma, having peers who use substances and easy access to nicotine, alcohol or drugs. Genetic vulnerabilities are thought to account for approximately 50 to 75% of the risk for addiction. Because we are not aware of our exact genetic susceptibilities, it’s difficult to predict with any level of certainty who will and who won’t develop addiction. That’s why it’s so important to minimize as many risk factors as possible and boost those factors that are known to protect against developing addiction.

In general, treatment is most effective when delivered by a qualified provider; when the nature, intensity and duration of the treatment is tailored specifically to the patient’s circumstances and needs; and when the patient is treated with dignity and offered the social and life supports needed to resume healthy life functioning.”

Q: How has our understanding of addiction as a brain disease enhanced our ability to treat substance abuse?

A: Understanding how addiction is caused by changes in the brain and is perpetuated by physiological processes helps underscore the fact that addiction is a treatable condition that responds well, in most cases, to professional therapy, medication and other supports, and that renders punitive measures mostly ineffective. Additionally, understanding where and how the brain is affected by various substances allows for the use of targeted treatments, such as medications, to lessen, block or reverse the effects of the substance. It also highlights the importance of delivering treatment for whatever duration and intensity is needed, and to do so in a variety of settings—rather than just the traditional 28-day detox or rehab facilities—as is true of other health conditions and diseases. Finally, it shows why incidents of relapse should be met with considered adjustments to the treatment regimen rather than with shame and blame.

Q: More specifically, how does it play into Center on Addiction’s treatment?

A: Center on Addiction does not provide direct treatment services. Instead, our work focuses on researching and advancing effective prevention and treatment strategies and policies that promote effective care, while also providing support and guidance to families. Our work on prevention, for example, draws on the research demonstrating how early use changes the brain to make it more vulnerable to addiction, underscoring the importance of preventing early initiation of substance use.

Similarly, our work on treatment supports the use of medications for substance use disorders as well as evidence-based behavioral therapies that address the specific changes to the brain wrought by substance use. We also work to encourage the implementation of policies that address addiction as a disease and support and promote access to evidence-based therapies. Finally, we strive to reduce stigma by informing the public—including families of children with addiction, educators, health professionals, and policymakers—that addiction is a health issue rather than a moral failing, and provide them with the support and tools they need to offer effective care to those at risk for or who already have addiction.

Q: What are a couple of the most promising treatments?

A: For opioid use disorder, the most effective treatment has proven to be medications—i.e., methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone—which can be enhanced by behavioral therapies. There are also medications to help treat alcohol and nicotine use disorders. Substance use disorders can be treated effectively through psychological or behavioral therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management.

In general, treatment is most effective when delivered by a qualified provider; when the nature, intensity and duration of the treatment is tailored specifically to the patient’s circumstances and needs; and when the patient is treated with dignity and offered the social and life supports needed to resume healthy life functioning.

Q: In your mind, how far has the study of addiction as a brain disease come over the past couple decades? What has driven it forward?

A: The study of addiction as a brain disease has come a long way over the past few decades, as new imaging technologies became available that allowed scientists to study the brains of people with addiction. Research in public health and epidemiology have also grown and contributed to a more nuanced understanding of substance use and addiction. The research has led to a scientific consensus that addiction is a disease that affects the brain and body and is, in most cases, exacerbated or attenuated by environmental conditions, but also responsive to effective treatment.

In fact, because the scientific evidence is so abundant and irrefutable, policymakers, who historically have been on the forefront of relegating addiction care to the criminal justice system, now regularly refer to addiction as a disease. They have begun to embrace the scientifically sound perspective that it should be treated by qualified and trained health professionals. This has allowed for a movement, albeit slow and insufficient, toward providing insurance coverage for addiction treatment and away from using a punitive model toward those with addiction.

Q: Do you feel we’ve just scratched the surface in our understanding of the links between addiction and disorders of the brain? Along those lines, what might the future of addiction treatment look like?

A: There is definitely more research that can and should be done on addiction and the brain, particularly in terms of developing medications for non-opioid substance use disorders—such as stimulants—developing vaccine-like therapies that reduce the risk of addiction and detecting and modifying genetic and physiological vulnerabilities to addiction. Additional research may also lead to new or more effective treatments for opioid and alcohol use disorders and increased opportunity for more individualized treatment approaches.

There’s also good evidence that addiction is more likely to affect individuals with mental health disorders. Although this relationship can be accounted for by common psychological, familial and environmental vulnerabilities, there may be shared physiological determinants of susceptibility to these disorders. A better understanding of what those might be can open up the field to new, life-changing treatments and therapies.