Study of deep brain stimulation offers a new frontier in addiction care

By Jason Langendorf

September 7, 2020Dr. Frank Plummer was a world-renowned Canadian microbiologist who operated on the leading edge of the global response to Ebola, SARS and H1NI swine flu, and his award-winning work on HIV broke important ground in the clinical understanding and treatment of that virus.

He was also an alcoholic.

After years of working under anxiety- and adrenaline-fueled conditions, often halfway across the world, Plummer found himself unwinding every night by drinking nearly an entire bottle of scotch. He would try various tactics, programs and rehabilitation facilities to address what he came to recognize as an addiction, but nothing took. Eventually, he grew sick, nearly died and received a liver transplant in 2012.

Three days after his transplant, as Plummer described in a January episode of the “Elevation Recovery” podcast—cohosted by opioid recovery coach Matt Finch and alcohol recovery coach Chris Scott —he tucked his IV into his shirt, walked into a bar and began drinking wine.

“My thought process at the time was: I need to do something or I’m going to die.”—Frank Plummer, patient No. 1 in the North American surgical trial for deep brain stimulation

What he did ultimately may be remembered as yet another groundbreaking achievement with the accomplished scientist at its core: In December 2018, Plummer became Patient No. 1 in the first North American surgical trial of deep brain stimulation (DBS) for treatment-resistant alcohol use disorder (AUD). Conducted by Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto, the study was performed to determine the safety of DBS in patients with AUD for which other treatments hadn’t been effective.

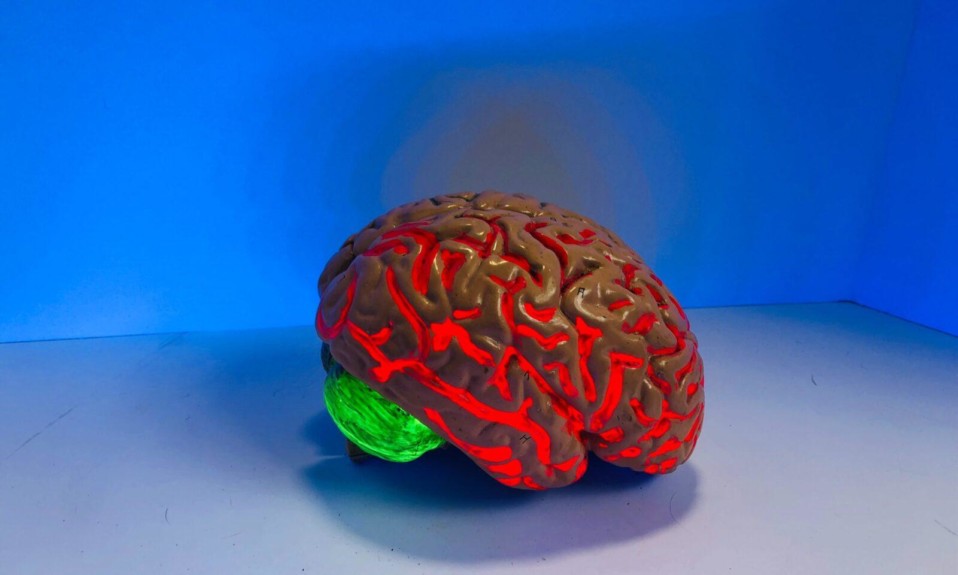

DBS has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the treatment of essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease since 1997, and go-aheads followed for conditions like obsessive-compulsive disorder (2009) and epilepsy (2018). But comparatively less human research had been conducted on DBS in the treatment of AUD, which affects a different part of the brain.

The DBS procedure implants electrodes in the brain—in this case, the nucleus accumbens, which is an important area of the brain with regard to addiction. The mechanism is likened to a pacemaker for the brain, emitting regular pulses of electricity to aid in the regulation of cravings, mood and anxiety. Plummer’s improvement, complicated by cancer treatment, manifested gradually but unquestionably. He began cooking, started work on a book and created a biotech company.

Our investigation into the safety of deep brain stimulation in treating this disease will be a key factor in helping patients who aren’t responding to therapy and medication, and may one day offer another option for treatment.”—Dr. Nir Lipsman, neurosurgeon and director of Sunnybrook’s Harquail Centre for Neuromodulation at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto

The ongoing DBS research holds promise because AUD, essentially, rewires the brain and leads to a high incidence of AUD relapse even after traditional treatments. But the procedure isn’t a cure-all—nor does it come without some measure of risk. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons has deemed DBS “safe and effective” in appropriate patients, but risks and side effects range from headaches, speech or vision problems and loss of balance to infection and brain hemorrhage (1% risk). There is also the chance that for some patients, quite simply, it won’t work.

“Research has shown patient response to DBS varies,” said Dr. Peter Giacobbe, psychiatrist and clinical lead at Sunnybrook’s Harquail Centre, in a hospital report responding to the group’s work on DBS treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. “Some individuals may respond to treatment and others may not, while some patients may find symptoms improve slowly over time.”

Plummer died in February, reportedly of a heart attack. But in his two years after undergoing the DBS procedure, he found it to be life-changing. “I feel happier than I have in a long time,” he said. “I feel joy for the first time in a long time. So it’s been, for me, a miracle.”

Source: Natasha Connell