A mindfulness-based approach to addiction meets immersive tech to enhance patient engagement and program adherence

By Jason Langendorf

December 8, 2020Let’s say you’re a person who wants to stop drinking, or who would like to reduce alcohol consumption. You’re seated at a bar when a bartender asks what she can pour you.

You turn down the offer, walk away and cope with your cravings, feelings and self-denial with positive strategies that lead to better life outcomes and a stronger resistance to drinking in the future.

Sounds pretty helpful, right? That’s what a VR company is doing by enabling you to visualize and practice your way to saying “no.”

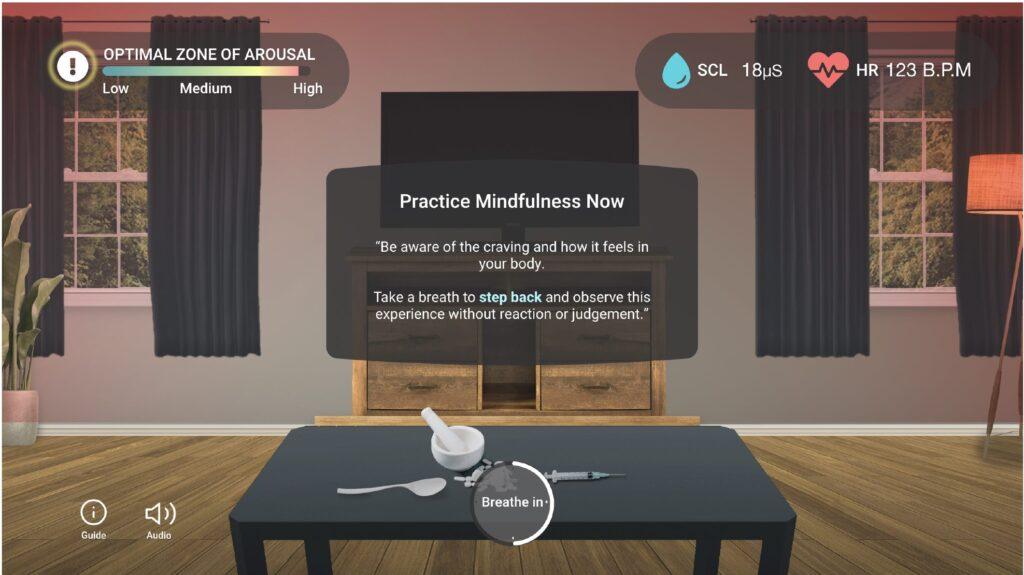

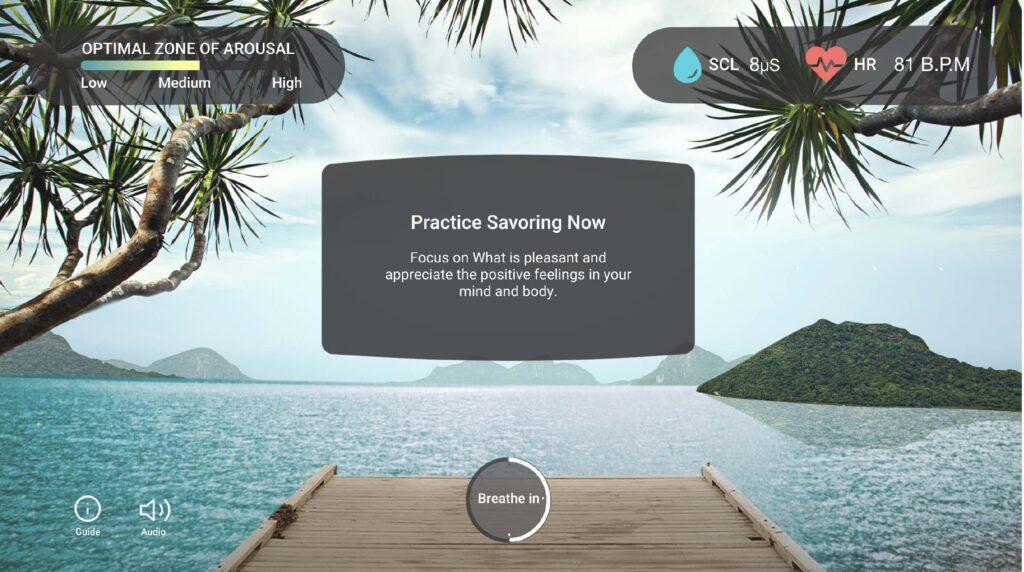

Virtual reality tech company BehaVR taps the power of immersive technology and mindfulness-based treatment to help patients struggling with addiction learn and strengthen coping skills, and possibly even “re-wire” their brains.

BehaVR’s Dynamic eXperience Engine (DXE) is a cloud-based platform that creates a dynamic, personalized VR experience for the patient and a logged user response record for clinician visibility and future program enhancement.

At the core of the company’s treatment programs is its SAFE protocol (Stress, Anxiety and Fear Extinction), a form of exposure therapy. Its engaging experiential content journey delivered through the VR headset, according to BehaVR, helps patients activate neuro-cognitive pathways for emotional regulation, stress resilience and craving control.

VR works very much like real life, where we can put you in scenarios where we can trigger your emotions on purpose—to a degree, put you in exposure scenarios where you react to them much like in real life. And then we can also teach you how to regulate in that circumstance.”—Pete Buecker, M.D., BehaVR chief medical officer

Or as BehaVR founder and CEO Aaron Gani puts it: “What we’re doing with our platform and with our experiences is using the medium of virtual reality to address, stress, anxiety and then, through exposure therapy, extinguishing things that are either fear-inducing or triggering for individuals.”

Gani, who previously worked on technologies and member logistics for the health insurer Humana, has spent much of his career searching for ways to improve patient outcomes while reducing costs on healthcare systems. At BehaVR, he considers VR to be an important step toward achieving both those goals. With regard to the addiction recovery space, he uses the bar scene as an example of how virtual reality can help.

“It’s building cue refusal skills,” Gani says. “It’s exposure to the thing that triggers you. In the case of recovery, it could be my desire to take that drink. But it could also be, like in our social anxiety programs, more like the stressful social situation—so that’s that fear extinction or exposure element of the SAFE protocol.”

BehaVR Chief Medical Officer Pete Buecker, M.D., was the primary developer of the company’s SAFE protocol, which is an extension of his focus on the intersection of chronic stress, emotional dysregulation and anxiety. In the course of his work, as well as through his personal search for stress reduction, he “became very interested in the prospect of using technology and digital solutions to help meet the scale of what I saw as an insurmountable problem in the system—just people falling into the cracks all over the place.”

Buecker calls chronic stress “the biggest elephant in the room in all of healthcare,” associating its presence with a number of mental and behavioral health symptoms and conditions, including addiction.

Buecker says BehaVR—which patients access through a treatment provider and then use in real-time sessions conducted in a clinical or home setting—is designed to help address those stressors, building a patient’s regulation skills with tech that helps create lifelike experiences. He likens it to an NFL quarterback using VR to “play” against an opposing defense in POV, 360-degree game situations versus watching 2-D game film.

“You’re trying to imagine it in your frontal cortex and then generate an emotional reaction to that, then do something with it,” says Buecker. “But in real life, that’s not how it works. VR works very much like real life, where we can put you in scenarios where we can trigger your emotions on purpose—to a degree, put you in exposure scenarios where you react to them much like in real life. And then we can also teach you how to regulate in that circumstance.”

“It’s like you’re learning experientially,” Buecker adds, “as opposed to trying to see something or hear something and then commit it to memory and bypass everything that you’ve known before—trying to commit that to your memory somewhere, with all the resistance that comes up around, [whether] it’s too much [or] not enough.

“In VR, it’s just very different. We can sort of grease those pathways.”