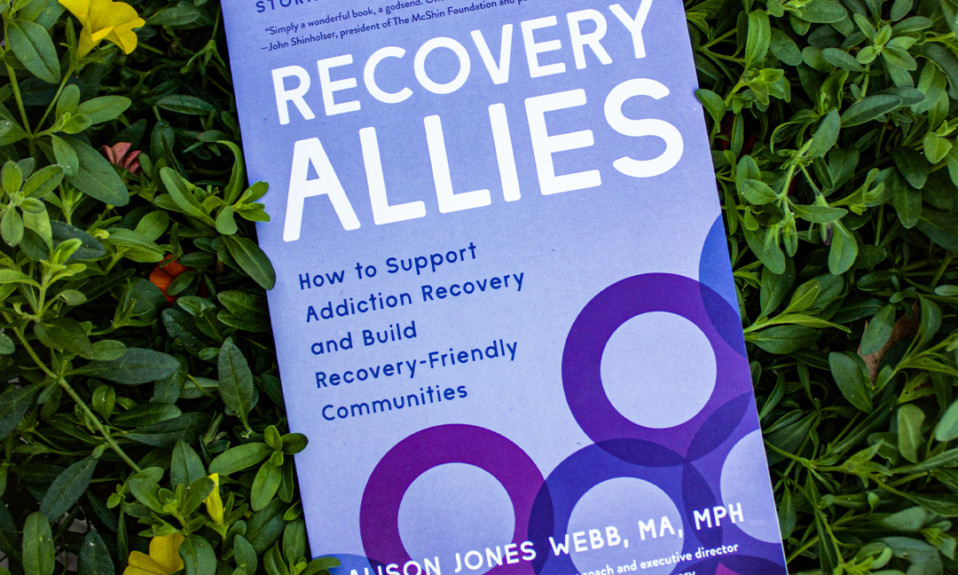

Recovery Allies is an essential guide to building supportive communities for those in recovery—something that benefits everyone

By Mark Mravic

In her smart, provocative and eminently useful new book Recovery Allies, Alison Jones Webb delves into a concept that she hopes will transform the way people think about the world they live in: the “recovery ecosystem.” We are, for the most part, thankfully moving past the era when addiction is seen as a moral failing, a problem to be tucked away or whispered about, a private matter left to the individual and their close family members to deal with. More than ever, given the growing overdose crisis, addiction is a matter of public and community health. So too, Webb contends, must be recovery.

At its most immediate, of course, recovery still centers on an individual, a close network of support and the team of professionals who provide care. But as Webb, a contributor to TreatmentMagazine.com, writes, effective recovery involves a much wider array of forces and influences—not just personal characteristics, but family relationships, social networks, economic factors, cultural norms and more. Crucially, she notes, “We all live in this recovery ecosystem.” [Emphasis added.] In short, she argues, it is up to all of us to create the conditions that support and promote recovery—to become partners in recovery and create recovery-friendly communities. That doesn’t just help people in recovery; it makes for stronger, more enriching and successful communities for everyone.

Drawing from a wealth of personal narratives, current research, examples of community action and her own experiences as a Maine-based recovery advocate, Webb explores what recovery means (its many meanings, in fact), how it differs for people and groups, its various stages, and common threads that run through recovery in all its forms. She provides in-depth discussions of how to build recovery capital and what it means for a community to be recovery-friendly. There are sections, informed by the latest research, on stigma, harm reduction, trauma and mental illness, physical and spiritual health, and addiction medication; explorations of housing, education and employment as they relate to recovery; and discussions of the place of community organizations, peer support and advocacy in building recovery-friendly communities. Interspersed throughout the book are helpful sidebars—notes on language and terminology, scientific and pharmaceutical information, policy issues, plus charts and checklists—and stories from dozens of interview subjects that illuminate the author’s points.

What makes the book especially valuable is spelled out in the subtitle: “How to Support Addiction Recovery and Build Recovery-Friendly Communities.” Indeed, at its heart Recovery Allies is a practical how-to guide. Each highly informative section concludes with a list, under the heading “What Can Allies Do?”, of detailed, real-world steps the reader can take to contribute to a recovery-friendly community. The guidelines are subdivided for different categories of reader. Just a few examples:

- For Everyone

- For Friends and Family Members

- For Health Care Providers, Social Workers and Clergy

- For Community Organizations

- For Policy Makers

- For Employers

- For College Administrators

Some of the suggestions call on the reader for introspection:

- “Think about your own drug and alcohol use”

- “When someone tells you they have trauma, believe them”

Others are a call to action:

- “Invite people in recovery to serve on your boards, committees, advisory groups, and coalitions”

- “Offer public statements that make it clear your congregation welcomes people on all paths of recovery and back them up by showing up at recovery events in your town, such as community meetings or recovery rallies”

- “Carry naloxone!”

Yet others are simple, practical steps:

- “Ask your loved one or friend with children if they would like you to babysit while they go to meetings”

- “Ask your loved one if they would like you to help with insurance details”

The solutions offered are voluminous and sometimes narrowly targeted depending on the topic. A few more examples:

- For artists: “Consider holding writing workshops for people in recovery and their families or recovery poetry readings or recovery rap competitions. Look into hosting a recovery art show or including works by artists in recovery at local galleries.”

- For employers: “Include people in recovery on workplace wellness committees. … Check the health insurance benefits you provide employees to be sure substance use treatment (including multiple rounds of treatment) is reimbursed at a reasonable rate for employees and their family members. Make sure employees know about their benefits.”

- For landlords and property management companies: “If you rent to recovery residents, help reduce stigma by sharing your experiences and becoming a spokesperson for people in recovery, including at local landlord associations.”

Webb means for these suggestions to result in practical action, and no doubt they will, since they’re easy to accomplish and make eminent sense. But there’s also an intangible effect, which may be just as profound and important, as we read through and contemplate all these ideas and the diverse range of people they encompass. We’re struck with the sense of how much can be done, and how everyone has a part to play. Just as individuals in recovery run the gamut of age, status, profession, race and gender, we realize from this book that so too do potential recovery allies. As Webb writes, “Regardless of your role or position—family member, neighbor, artist, person of faith, welder, business owner, librarian, law enforcement officer, doctor, lawyer, college dean, farmer, shipbuilder, carpenter, government official, and more—you can be part of creating and sustaining a recovery-friendly community where you live.”

Recovery Allies is a one-of-a-kind book, an incisive and essential guide to the recovery ecosystem that we all inhabit—and in which we all have a role.