Bennet Davis, director of Sierra Tucson’s pain recovery program, says that many aspects of the drug plague are misunderstood

By Jenny Diedrich

As an expert in pain management, Bennet Davis, M.D., has watched America’s opioid crisis unfold from an up-close vantage point.

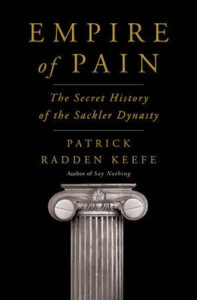

Davis, founder of the University of Arizona Pain Center and its director from 1995 to 2002, is now director of the pain recovery program at the addiction treatment center Sierra Tucson. He lived through the era when pharmaceutical reps urged physicians to freely dispense their painkillers, and his experiences give him a keen perspective on the recent book Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, by New Yorker journalist Patrick Radden Keefe. The bestseller examines the Sackler family, which founded Purdue Pharma, and its role in the opioid epidemic, with its wanton distribution of OxyContin.

“When I read Empire of Pain, I felt like a guy who had fought in World War II who was reading a book about World War II,” Davis says. “Those reps from Purdue Pharma were at my door, encouraging me and other pain specialists to prescribe their drug.”

He believes the book mistakenly refers to an “addiction crisis,” when in fact, he says, the Sacklers contributed to a crisis of accidental opioid overdoses. “Three out of four people I saw over a 15-year period who died of OxyContin had no addiction disorder at all,” says Davis.

Davis talked with TreatmentMagazine.com about the opioid crisis and Keefe’s book.

Q: You’re a medical doctor board certified in anesthesiology and pain medicine. Why do you choose to work at an addiction treatment center?

A: I came to work at Sierra Tucson to take advantage of the mental health treatment. My mission here is to find the people who are suffering the effects of undiagnosed trauma and grief, and get them out of the medical system. You have to have behavioral health resources to do the treatment. We evaluate patients and may see medical problems, but we also pull out the trauma part of it and sometimes addiction, too.

There is no quality evidence that the majority of people with psychological distress who were prescribed opioids for pain developed addiction disorders. My personal experience is that the majority did not. They died of accidental overdose because opioids are unforgiving.”—Bennet Davis, Sierra Tucson

The goal is to get patients to understand the connection between their biography and their biology. Chronic pain can be caused by trauma. I do the medical workup and address those issues while giving patients the confidence that they can take a break from chronic pain management and focus on trauma and grief. The results are so good that we call it pain recovery instead of pain management. If people are suffering chronic pain for a long time and not getting better, the trauma has been missed. Trauma recovery is chronic pain recovery.

Q: In your opinion, what are the myths about the opioid crisis?

A: That the opioid crisis is primarily a crisis of addiction. Initially, the opioid crisis referred to accidental overdose of prescription opioids. It was not until later that street drugs heroin and then fentanyl became a major part. It is well known that psychological factors—depression, anxiety, poor coping skills, chaotic lives—are the primary predictors for the onset of chronic pain and are the main reasons people fail the conservative treatment of pain. This tells us that people presenting with chronic pain are primarily struggling with psychological issues.

There is no quality evidence that the majority of people with psychological distress who were prescribed opioids for pain developed addiction disorders. My personal experience is that the majority did not. They died of accidental overdose because opioids are unforgiving. They were given high doses, and this population of patients would be more prone to impulsive behavior and poor judgment, such as taking an extra medication or having a few drinks when stressed. That’s not a substance use disorder—it’s an accidental overdose.

If we would have had a strong behavioral health program, we wouldn’t have had an opioid crisis. In the absence of effective mental health, America put its anxious, depressed population on opioids.”—Bennet Davis

The second myth is that the opioid crisis was the creation of Purdue Pharma. The opioid crisis was made possible by an underfunded behavioral health system and inadequate screening and resources to treat behavioral health problems. If we would have had a strong behavioral health program, we wouldn’t have had an opioid crisis. In the absence of effective mental health, America put its anxious, depressed population on opioids. Health plan decisions to defund behavioral health treatment of pain in the late 1980s and early 1990s opened the door for Purdue Pharma to introduce oxycodone as the new treatment for pain.

Q: Does Empire of Pain propagate these myths?

A: Throughout the book, the author refers to the opioid crisis as a crisis of addiction. The author alternates between describing the opioid crisis as a crisis of overdose death—correct—and a crisis of addiction. He doesn’t distinguish between people with addiction disorder who were using oxycodone that had been sold on the black market and people with undiagnosed psychological trauma and other behavioral health issues who were prescribed opioids. It is the latter population that dominated accidental overdose in my community, although there is not a rigorous epidemiology description of this phenomenon, probably because so many bought into the Purdue marketing narrative that people who overdosed on OxyContin were addicts.

The opening chapter of the book is called “Tap Root.” In this chapter, the author makes the case that the ultimate cause of the opioid crisis in America is Purdue Pharma marketing. The true tap root of the opioid crisis is the failure of American medicine to address the psychological factors that are the tap root of chronic pain.

Q: What does the book do well?

A: The book highlights the danger of underfunding mental health in our country. For the addiction recovery community, the danger is that we will not truly help people recover if we don’t adequately address the mental health tap root of addiction. The book highlights how underfunding behavioral health evaluation and treatment resources can add fuel to the addiction fire.

For the community at large, the book does an excellent job of describing just how powerful big pharma is. It can influence provider thinking, attitudes, beliefs and treatment plans. It can reach into our government agencies and influence them. I recommend the book to medical and nursing students to help them understand the need to be vigilant about sorting out quality medical evidence from pharma marketing.

Second photo from top: JESHOOTS.com