The medication has worked wonders for many people with OUD. So, why is it so hard to get?

By Alison Jones Webb

“Suboxone saved my life,” Danielle Rideout told me. “I’m a licensed alcohol and drug counselor. I’m going to grad school. I own a house, and I have two children. I’m married to the man I’ve been with for 15 years. We have all these things, and they’re all a direct result of my recovery. I truly believe Suboxone did that for me.”

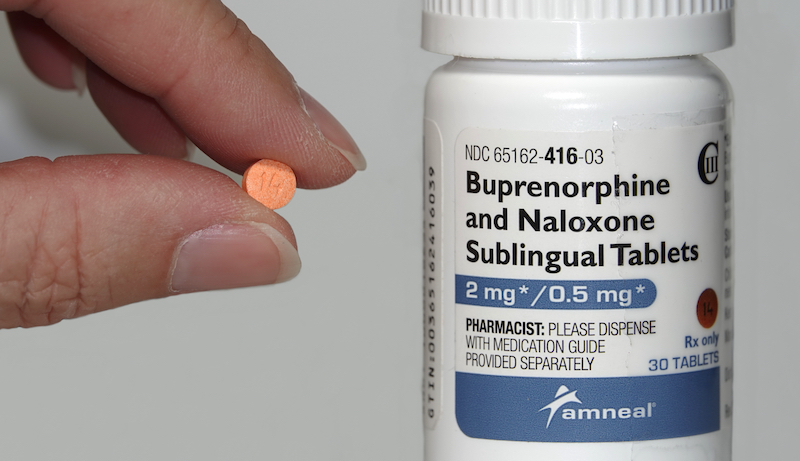

Rideout and many people like her credit Suboxone (the trade name for buprenorphine) with her success in early recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD). Yet access to buprenorphine has been limited compared to the number of people seeking help since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it in 2002. At that time, buprenorphine was touted as the new “gold standard” in addiction treatment, a status formerly held by methadone. Buprenorphine could be prescribed or dispensed in primary care offices, and the hope was that this would significantly increase access to treatment compared to methadone, which had to be obtained at a limited number of heavily regulated clinics.

That hope hasn’t become reality. In 2015, 13 years later, researchers identified a treatment gap of over one million people in need of OUD treatment compared to buprenorphine prescriber capacity. The gap is especially large in rural areas.

The Buprenorphine Gap

The treatment gap is created, in part, by limitations in the law that allow prescribers to treat just 30 patients at a time. That number increases to 100 patients for providers who have prescribed for at least one year. In the 20 years since FDA approval, research has identified numerous barriers that providers face in prescribing buprenorphine.

Primary care providers consider the lengthy training required in statute to obtain a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD treatment—commonly referred to as the “waiver training”—to be a barrier. Another hurdle is the required referral to counseling and other psychosocial services, particularly in rural areas where those supports are in short supply. These barriers hold true for physicians, as well as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists and certified nurse midwives, who were added as eligible prescribers later. (The training requirement is eight hours for physicians and 24 hours for other prescribers.)

Private and public insurance reimbursement for office visits, counseling services and buprenorphine has also created challenges.

Some prescribers are concerned about diversion of buprenorphine to non-medicinal uses and are reluctant to prescribe it. Many prescribers have little or no institutional support, including access to mentors or addiction specialists to help with these complex patients. Some prescribers report competing time demands as a barrier. Research suggests that negative attitudes toward patients with OUD and with substance use disorders more generally also present obstacles to prescribing. Private and public insurance reimbursement for office visits, counseling services and buprenorphine has also created challenges, with prior approvals and restrictions on length of time in treatment acting as impediments that vary across states.

The End Result

The upshot is that even when eligible clinicians complete the waiver training, they don’t end up prescribing. One study in 2020 indicated that about half of clinicians who completed the training went on to receive a waiver; of those, just 36% were prescribing buprenorphine at a follow-up.

With much of the drug supply now including the illicit synthetic opioid fentanyl, the stakes are high, and access to this OUD treatment is more important than ever.

In April 2021, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and the continued rise in opioid overdose deaths, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) eased restrictions on prescribing buprenorphine to address some of those barriers and increase access to effective treatment. Now, the same eligible prescribers may treat up to 30 patients without completing the waiver training, and they’re not required to refer patients to psychosocial support. This creates opportunities for primary care providers as well as providers in emergency rooms to prescribe buprenorphine more widely.

It’s too early to tell if these changes, and others that states and healthcare organizations are implementing to address reimbursement and access issues, will cover the enormous treatment gap. For people like Danielle, buprenorphine is a crucial part of overall recovery. With much of the drug supply now including the illicit synthetic opioid fentanyl, the stakes are high, and access to this OUD treatment is more important than ever.

Alison Jones Webb, MA, MPH, is the author of Recovery Allies: How to Support Addiction Recovery and Build Recovery-Friendly Communities, which will be published by North Atlantic Books in September 2022.

Top photo: Shutterstock; bottom photo: Nic Y-C