After spending decades talking about the troubles that took his famous brother Chris, Tom Farley has switched the focus to others—including himself

By Jason Langendorf

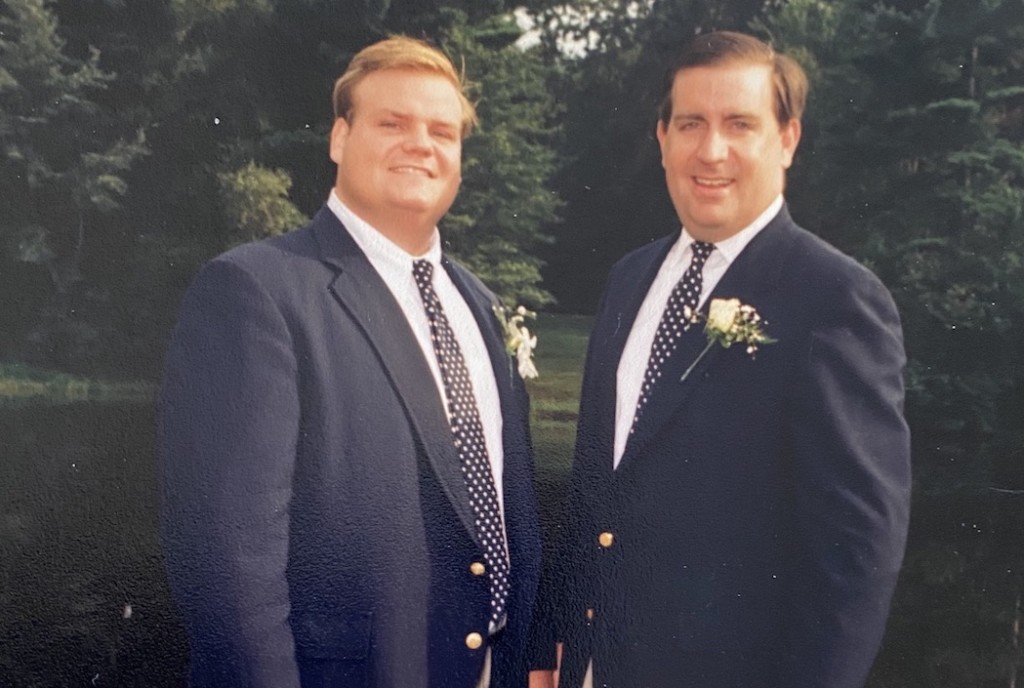

When his brother died from a drug overdose more than 20 years ago, Tom Farley experienced it in much the same way as anyone who has lost a loved one to addiction.

With one difference: Tom’s brother was Chris Farley, the comedian and actor best known for his uproariously manic and sweet characters on TV’s Saturday Night Live and in films like Tommy Boy and Black Sheep. In December 1997, while the television and film industries and fans across the world mourned the passing of an authentic and iconic performer, Tom Farley felt a hole where his younger brother used to be.

When I first spoke to Tom and promised that our discussion wouldn’t just amount to a long series of questions about Chris, he chuckled. “He’s always there, right?”

When [Chris] died, I felt this need to go into schools and just tell the story, hopefully do something good that could come from his death. So I started going into schools, and it wasn’t really comfortable. It just wasn’t me.”

—Tom Farley

And that’s the idea, as far as Tom is concerned. The oldest brother in the Farley family, Tom is warmed by the continued interest in Chris after all these years. He has played a central role in honoring his brother and stoking our memories of his talent and heart, founding the Chris Farley Foundation in 1998, co-authoring The Chris Farley Show: A Biography in Three Parts in 2008 and speaking around the country as an advocate for drug prevention and treatment.

“When he died,” Tom says of Chris, “I felt this need to go into schools and just tell the story, hopefully do something good that could come from his death. So I started going into schools, and it wasn’t really comfortable. It just wasn’t me.”

Delivering Tough Lessons with a Laugh

Serving as a marketing director for multiple financial service companies based in New York City during Chris’s SNL years, Tom was a communications pro who had spent plenty of time around Chris while he was sharpening his comedic chops. The only Farley brother from the Madison, Wis., family who didn’t strike out to pursue acting and improv comedy, Tom nevertheless came by his entertainer’s streak honestly. His dad, Tom Sr., a salesman by trade, was by all accounts a larger-than-life personality, and the Farley siblings grew up seeking attention and validation by hunting for the big laugh. Tom knew instinctively that the worst thing he could do was lose an audience.

“I started to really look at how my brothers did it,” Tom says. “Not only using their skills in comedy and humor, but looking at how they did it. They’re all Second City-trained. I was like, ‘Well, what is this improv stuff?’”

Tom began studying the roots of improv, which, most agree, began with the teachings of a Chicago social worker. Viola Spolin created games that encouraged interactions between children, especially those who spoke different languages. In 1955, Spolin’s son, Paul Sills, began America’s first improvisational theater, the Compass Players, and later co-founded the Second City Company. Improv is now used as a form of therapy (psychodrama), and techniques such as the “Yes, and” rule that sprang from the form are now applied in sketch comedy, self-help circles and business communications.

Deciding to pursue improv further, Tom took a class at Second City in Chicago, discovered more of the values it fostered—communication, trust—and then began teaching it to students in the schools he visited on his speaking engagements.

“I said, ‘Well, maybe by communicating better by creating ensembles, as they say in the improv world, that will go a long way toward helping them. So we did, and it was very impactful. I’d walk out of schools after getting 100% attention from classrooms, and teachers would be like, ‘How did you do that? I can’t even get 20% of them to pay attention.’”

Over time, Tom was further drawn to the treatment and recovery elements of his charitable work. He moved back to Madison, visited at-risk groups of teenagers and began applying improv principles to help them connect in therapy sessions. “You’ve got freshmen, sophomores, juniors, seniors—you’ve got different genders—and you’re putting them in a room and telling them, ‘Share.’ They’re not gonna share! So I said, ‘Let me come in there, and for 45 minutes, let’s just do improv. Start to create the ensemble, start to create trust.’

“I just felt that this was more comfortable, to be in that situation. Because I saw Chris struggle through all his various treatments, up and down, in and out of treatment places. And I knew that that was where the real struggle was.”

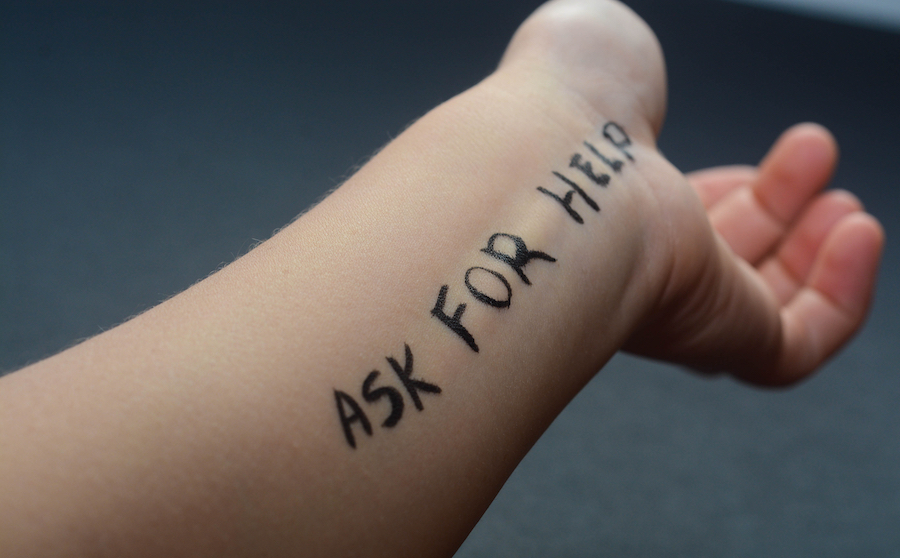

Coming to Terms with His Own Addiction

Three years ago—two decades after Chris’s death—Tom acknowledged his own struggles. After growing up in a family with big appetites and having been embedded for years in Wisconsin’s tavern culture, Tom had a vague sense that he wanted something else, a different example for his own children. He would abstain from drinking for years at a time, which he considered affirmation enough that he didn’t have a problem.

For 20 years, I was talking about somebody else’s addiction, somebody else’s recovery. … All of a sudden, it was time for me.”

—Tom Farley

“But life hits you,” Tom says. Stress had its way. And although he was managing his responsibilities, his own drinking would come roaring back. He says he used patients in the recovery programs he worked with as a barometer. Eventually, after all of his time spent in treatment facilities and around those in recovery, something clicked. Tom realized that sobriety in and of itself wasn’t a solution. He would look around the room, see others with addiction, and recognize trauma, insecurity and anxiety. He saw, for the first time, their commonalities as his own: They were all coping with something else.

“For 20 years, I was talking about somebody else’s addiction, somebody else’s recovery,” Tom says. “And, you know, it was great—great stories, a great name. That people are still talking about Chris is amazing. But all of a sudden, it was time for me.”

Tom Farley has maintained his sobriety in the three years since, which he calls “fantastic,” in part because it has helped bring him the clarity to understand the deeper nature of his substance use. He has continued following a path into the addiction treatment and recovery space, joining the Rockford, Ill.-based addiction treatment provider Rosecrance as community relations coordinator in March.

“I wanted to remain in Wisconsin, and Rosecrance was looking for Wisconsin reps,” Tom says. “I’m like, ‘That’s perfect.’ When I saw the opportunity, I was like. ‘First of all, I need you—but, also, you need a Wisconsinite.’ Because if you want somebody up in Wisconsin talking about your treatment center, you need somebody that knows the culture. I mean, you can’t just send somebody from Illinois up here.”

As ever, the Farleys know their audience.